Blake F. McKelvey's 1972 A History of Penal and Correctional Institutions in the Rochester Area

[McKelvey pages 16 through 22] The prestige of reformatory penology reached a peak in the late nineties, but gave way gradually to new approaches after the turn of the century. Brockway's confidence that all his first offenders could advance through successive grades to full rehabilitation failed to take account of those who had limited capacities, and his attempt to paddle one feebleminded inmate into conformity brought his own illustrious career to a close in 1899. Concern for the welfare of defective and insane persons had prompted the establishment of asylums in New York and other states in earlier decades, and William Pryor Letchworth had taken the lead in 1892 in the development of Mattewan, the first penal institution in the country for defective and insane prisoners. Seven years later an institution at Napanoch, originally planned as a branch for Elmira, was designated for the care of male defective delinquents, and the Western House of Refuge for Women, opened in that year at Albion as a branch of the women's reformatory in Hudson, was similarly converted to the care of female defectives in 1930 and renamed the Albion State Training School. The removal of these unfortunates relieved the reformatories and the prisons of some difficult charges, but focused attention on the need to study and classify each convict in order to place him in the institution that best fitted his character and needs.

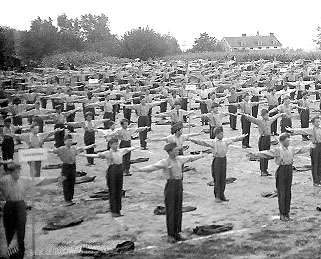

In the Rochester area only the State Industrial School remained totally committed to its reformatory objectives. With other juvenile institutions it escaped inclusion among the penal institutions placed under the central jurisdiction of the State Prison Commission on its creation in 1877 and retained its character as a correctional institution under the supervision of the State Board of Charities. Its local board of managers had begun in 1888 to debate the merits of the family or cottage system as an alternative to the traditional congregate cell blocks, and in due course the aging character of the buildings and the need for costly improvements prompted the State Board of Charities to determine in 1903 to remove the school to a new site in Rush, 15 miles south of Rochester, and to rebuild it on the cottage plan. Construction commenced a year later on the 1400-acre site and the first boys began to move out in 1905; two more years elapsed before the old structure was finally abandoned. The new institution, renamed the State Agricultural and Industrial School, was comprised of 20 scattered cottages, each designed to accommodate 25 boys who bunked in one or two large dormitory rooms and shared a family dining room, a large living room, and other household facilities with a resident staff member and his wife as guardians. Farm chores, centering around an adjoining barn, supplied the major outdoor occupations; school work took place at first in the cottage workshop or the living room, somewhat on the pattern of the old district schools still prevalent in rural areas. The decision to make it an institution exclusively for boys eliminated a problem that had plagued its predecessor in recent decades in Rochester, and its location in a rural setting freed it from some urban distractions. But that circumstance ill prepared the boys for their return to homes that were generally located in Rochester or in other cities and towns of western New York. To meet this difficulty the State created the post of parole officer and in 1913 named the warm spirited Dr. Algernon Crapsey to that position. In the first years at Industry most of the boys were busily engaged in making their new cottages and farms more habitable. As superintendent, Franklin H. Briggs, formerly an instructor in the trade school, took advantage of the need for sidewalks, water lines, additional animal shelters, and farm fences to develop practical skills in which the boys could take pride. Although a number of boys escaped, 16 on one occasion, most of them were quickly apprehended and returned, and the administration adhered to its plan to make it an institution without walls.

Its managers banned the use of locks and keys at all but one security cottage, which was reserved for intransigents. When in 1912 Briggs resigned to accept the challenge of establishing another new industrial school, his chief assistant carried on until the appointment of Hobart A. Todd in 1918. Under Todd's leadership the school at Industry began to acquire its present-day character. . . . the need for more systematized industrial training as well as schooling prompted a re-emphasis on these aspects of the school's functions. When state plans for a new industrial arts building were blocked by the onset of the depression, Andrew J. Johnson, who succeeded Todd in 1929, secured a PWA grant to construct the new training center. Its completion made space available in the administration building for new psychiatric offices and other counseling services.

Unfortunately as the depression deepened and it became more difficult to find suitable homes into which the boys could be paroled, restlessness mounted and increasing numbers made a break for freedom, sometimes pilfering from neighboring farmers in the process. James S. Owens, superintendent in the mid-30s, answered the renewed protests with the argument that the state did not want to convert Industry into a prison, and that the solution lay in a more careful selection of staff members and a more imaginative training of the inmates. Owens and Frank D. Morse, who succeeded him, developed an active recreation program and endeavored to make better use of the psychiatric and sociological interviews in placing the boys in congenial cottages and in planning their work and study assignments. The situation changed again with the outbreak of the Second World War. Opportunities for parole in the cities were enhanced for those with industrial skills, and instruction in the academic as well as the technological classes became more meaningful to the boys. With a shortage of workers in the fields, Clinton W. Areson, who became superintendent in 1940, instituted a program of hiring out boys from the school in small groups at 35 cents an hour and permitting them to keep their earnings. With the return of peace Areson and John B. Costello, who succeeded him in 1950, undertook the remodeling or replacement of most of the old cottages and other buildings but placed their major emphasis on the care of the four to five hundred boys in their charge. Costello revived a plan, tried out more than a half century before, of releasing some of his boys for vacation leaves with their families . . . His chief boast on his retirement in 1971 was that he had tried to recognize and treat each of the 15,000 lads who had come under his care during the 20 years as individuals.

Of course the School at Industry, which received commitments only from juvenile courts and only under 16 years of age and which was now under the supervision of the State Board of Social Welfare, not the State Commissioner of Corrections, was not in the same category with the state prisons and adult reformatories or even with the local county penitentiary and jail where a break for freedom was considered a serious threat to the public. Moreover the school at Industry, though a state institution and funded from Albany, had from the start a local board of inspectors or directors, and over the decades several able men, such as Thomas Raines, the Reverend Isaac Gibbard, and Frederick D. Lamb, had played key roles in the development of policy. Rochester area representatives on the State Board of Charities, notably Letchworth, Dr. E. V. Stoddard, and Mrs. Alice Wood Wynd, had also contributed significantly at various stages to its development. For more than half a century state civil service regulations had governed the selection of its superintendents and other professional staff members. In similar fashion the State Prison Commission, recently renamed the State Commission of Correction, with advisory supervision over all state penal institutions, has by virtue of its staggered appointments a bipartisan character. Its chairman, the responsible Commissioner, was appointed by and served concurrently with each successive governor who thus remained politically accountable. Since, however, all wardens were chosen from a civil service list, the state penal institutions escaped direct involvement in politics, but they could not escape the political demands of labor for an exclusion of the products of prison industries from the open market; nor did they escape the recurrent demands for greater security and the repression of convicted felons. Despite the establishment of classification clinics and the attempt to separate the less violent from the more intractable criminals, who required confinement under conditions of maximum security, repeated plans for prisons without walls were abandoned when a few dramatic escapes stirred popular alarm.

Even the Great Meadow Prison, erected in 1908-10 by convicts themselves as a detention center for those requiring only minimal restraint, added a wall 15 years later. Tentative experiments with work gangs on the roads, popular in times of labor shortage, gradually gave way before the recurring demands for greater security. The Monroe County Penitentiary, on the other hand, had a different experience. When the ban on the sale of prison-made goods was extended to county institutions, the Monroe penitentiary expanded its farm holdings to raise food for county institutions. As the farm increased from 250 to 6oo and finally to 1,000 acres, the successive superintendents despatched larger work gangs each morning into the fields, but on rainy or wintry days most of them had to be kept in idleness at the penitentiary. The prison school, designed originally to teach the three Rs to illiterate inmates, many of foreign birth, faced a new problem as the character of the population changed and brought an increased number of men who needed work skills and job training. Repeated criticisms of the aging penitentiary by state inspectors prompted the Democrats, briefly in control in the mid-30s, to apply for and secure a PWA matching grant of $500,000 to build a new institution equipped to provide industrial training. But the Republicans, who regained control in 1936, cut the application in half, substituting a medium security design with a fuller reliance on farm work. When in a referendum the next November the voters rejected the new plan, the state inspectors again condemned the old structure as the worst in the state and threatened to close it. Superintendent Homer E. Benedict, like his predecessors a former supervisor, persuaded the Supervisors that limited improvements would be sufficient to prolong its service. Asserting their home-rule prerogatives they ordered the installation of additional toilets in some of the cells and the equipment of a hospital room and library. |