|

Part 2 of a 3-part web version of a paper presented Nov. 15, 2013 at Researching New York 2013 by correctionhistory.org webmaster. Clicking lower case Roman numerals in Parts I and II accesses respective endnotes in Part III. Clicking that citation's numeral in Part III returns you to your place in Part I or II. A list of links

to access any of the 3 parts appears at bottom of each page.

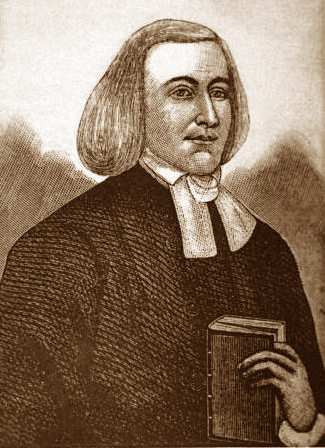

REV. JOHN STANFORD: U.S. & NY’s 1st STATE-HIRED &

PAID PRISON CHAPLAIN WASN’T PASSIVE The

fact is that Stanford – born Oct. 24, 1754, in Surrey, England -- did

during his long life often chose the more challenging course before him.

As a young man, he could have adhered to passive acceptance of the

established Church of England with which his family guardian, a rich

uncle, identified (apparently sometimes more in the breach than in the

observance). Young Stanford could have concentrated on the medical studies

which this worldly, well-off relative encouraged him to pursue. Instead,

John found himself drawn deeper into the religion of dissenters whose

preaching prompted him to personally research the New Testament on the

issue of baptism.

Booth, who delivered the major address at Stanford's 1781 ordination, was perhaps the leading voice at that time among those known as Particular Baptists. They believed, as did Calvin, that the atonement gained by Jesus' sacrifice is for an elect destined for salvation, not for all humankind in general as was belived by General Baptists following Calvanist dissenter Jacobus Arminius. Booth too, like Stanford, was an abolitionist.

Thus

young John joined the Baptists. By doing so, he may have gained a better

claim on heaven, but he suffered the loss of any claim on the inheritance

which previously had been earmarked for him by his uncle. The latter

changed his will after Stanford changed churches. But Stanford had been

aware beforehand of the financial risk in converting. In 1781, John was

ordained a Baptist minister during a ceremony in Hammersmith

church. With

both his parents and his guardian dead, no family ties to hold him to in

England and evidentially no church commitments to keep him there either,

he sailed for America Jan. 7, 1786. As he had left the church of his birth

to join a breakaway sect, so too now he left the land of his birth to join

a breakaway colony still very much just beginning to take shape as a

separate nation. Once again he took on the challenge of new birth in his

personal life.

After his service as chaplain in Gen. Washington's army during the Revolutionary War, Gano returned to his church on Gold St., in lower Manhattan, where he often let Stanford preach. When an opening for an interim minister became available at the First Baptist Church in Providence, R. I., Gano promoted Stanford's appointment.

Though

only a fill-in pastor at the Providence church, Stanford took on the

challenge of compiling the first history of the first Baptist church in

America. It was subsequently published in England and subsumed into A

General History of the Baptists by Rev. David Benedict who

acknowledged the New Yorker’s contribution: By

the efforts of this man of labor and skill, the records of the church

were collected, arranged, and placed in their present condition. The

author, Messrs. Knowles, Hague, and all historians since, have been

indebted to them for the few details which have been preserved, of the

doings of this ancient [Baptist] community.[v]

The Providence church was co-founded in 1638 by that fierce advocate of religious liberty, Roger Williams, an early abolitionist and true friend of Native Americans. The church styles itself the First Baptist Church of America.

Another

practice he initiated was regular theological instruction for the

university students at his parsonage since none was being offered as part

of the curriculum. These sessions laid the foundation for the university’s

school of theology. In 1788, Brown University trustees gave him an

honorary degree and elected him to their board. Before completion of his year as

interim preacher, the congregation asked he become its regular pastor.

But he declined, expressing a wish to return to New York labors he had

suspended. The

Rev. Charles G. Sommers, in his authorized biography of Stanford,

published by son Thomas Stanford’s printing company about a year after the

preacher’ death, employed a term worth noting (emphasis added here) in

reference to the First Baptist community of Providence, .

. . . [T]his was the first church in which Mr. Stanford was engaged as a

stated preacher in America.[vi]

Brown University, founded by Baptists, is said to have been the first college in the original 13 colonies to accept students regardless of religious affiliation. Originally called the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, it was renamed in 1804 to honor a member of the Brown family which had various involvements in its development.

Some applications of the adjective have fallen

into general disuse. A few of these linger on in special antique usage, as

when the NYC City Council or your local masonic lodge holds its stated

meetings, meaning those officially required by the organizations’

constitutions and bylaws. This

somewhat archaic meaning of the term is encountered in researching

Stanford’s becoming America’s first official prison chaplain in 1812 when,

as a later page in this paper notes, his services at Newgate became

“regular and stated.”

The Park Row lithographer's illustration depicts NYS chancellor Robert Livingston administering the oath of office on the balcony of Federal Hall, NYC, the first seat of Congress, on April 30, 1789. It had been City Hall. Some attribute to Washington the start of the practice common among Presidents being sworn to add ” so help me God.” to the words prescribed in the Constitution.

Perhaps a factor in the choice was the

attractive challenge posed by the prospect of preaching in the new

nation’s first capital. Thus, Stanford returns to New York in 1789, the

year and the city where and when George Washington is sworn in as

President and James Madison introduces the Bill of Rights for submission

to the 11 states constituting the United States at that point. North

Carolina and Rhode Island were hold-outs. R. I. had not even sent

delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Indeed, to persuade states

leery of creating a strong central government, the Federalists had to vow

amending the Constitution with a Bill of Rights, the very first of which

promised to safeguard the right of religious worship. That

Stanford had been concerned R.I.’s resistance to the Constitution would

lead to its spinning off as a separate country seems less likely a factor

in his decision to leave Providence than his wanting to be where the

action was centered for the rebirth of the nation under a new

Constitution: New York.

That Stanford married the daughter of a Trinity Church vestryman is consistant with the Baptist cleric's general non-sectarian approach, his personal friendships with Episcopal ministers and bishops, and his son, Thomas N., becoming a principle in the Episcopal publishing house of Stanford and Sword. After Trinity Church severed any connection with the established Church of England, only supporters of American Independence -- such as father-in-law Ten Eyck -- held Trinity Church office.

A

significant share of the monies raised by his preaching in and around the

city and by his religious tracts and books went into building a chapel for

his academy students and such believers as drawn to his preaching. But an

1801 fire destroyed the chapel, leaving only the pulpit intact. He took

this as a sign that he might not be meant to serve as a church pastor and

should concentrate on preaching and writing. People

were drawn to the non-sectarian, non-proselytizing character of his

preaching and writing. Stanford addressed people about their fears,

depressions, aches, pains, and other hardships in life, including those

brought on by their own behavior. He dwelt not on divisive doctrinal

issues. Rather he preached the broad basic Christian Good News that, thanks to God's

love for humans, He gave His Son Jesus to redeem them by suffering, dying and rising, and that an individual’s

own difficulties in life can serve as opportunities to open one’s self to

personally experiencing that redemptive grace and being spiritually

renewed through faith in Christ.

The above image, derived from a painting (circa 1777) by Charles W. Peale, shows Bloomfield in his Revolutionary Army uniform. He joined as a captain in the 3rd NJ Regiment in 1776, rose to rank of major, served a judge advocate, was wounded at Brandywine, and resigned the army in 1778 after being elected clerk of the NJ Assembly. After serveral terms NJ governor, he returned to military service at the start of the War of 1812 and served as Brig. Gen. on the U.S.- Canadian border. The N.J. town of Bloomfield is, in effect, named in his honor. He was president of the NJ Society for the Abolition of Slavery.

.

. . . I go on in the old ways. . . . good sir, I am what some people call

a “general lover,” by which you will understand that, although I maintain

with firmness the professions I believe to be the will of God, in his

gospel, I devote my public labors to all religious denominations

without distinction. Indeed, I am the only minister in this city that can

be called so far truly “republican.” To me, it is a source of peculiar

happiness that I receive the attention of Baptists, Independents,

Lutherans, Moravians, and others. I know you will not be angry with me for

this liberality. Semper eadem (always the same), preach where I may . . .

. . [vii]

Given

the ecumenical character of Stanford’s activities, how appropriate that an

Episcopal bishop authored the brief biographical sketch of the Baptist

minister published in a post-humorous second edition (1855) of the venerable

preacher’s last book, the Aged Christian’s

Companion:

A Variety of Essays for the Improvement, Consolation and Encouragement of

Persons Advanced in Life. Like the subject of his biographic essay about Stanford, Upfold was born in Surrey, England, but about 40 years after the Baptist's birth. Upfold came to the U.S. as a child whereas Stanford came as a young man. Both had studied medicine. Uphold moved onto theology after getting his MD whereas Stanford switched from medical studies to the ministry. Upfold stayed with the faith of his family, at least the independent American version, whereas Stanford had left the faith as well as the land of his birth. Yet despite the differences of age and sectarian affiliation, these two connected in New Yorkers and became friends. It was there that the younger began theological studies under Bishop Hobart and became deacon at Trinity Church.

Later, Upfold would serve as rector at St. Luke's in the Fields formed in 1820 by Greenwich Villagers on land made available by Trinity Church. In those days "the village" was the countryside, farm fields, the "sticks," hence the "in the fields" part of the name. St. Luke was chosen as its patron because not only was he considered one of the four New Testament gospel writers but also, according to tradition, a doctor. The village often served as a refuge to which NYers fled epidemics in "the city," which back then was centered in Wall Street's area. The first Church of Saint Luke in the Fields Eucharist is said to have been celebrated in a Newgate State Prison watch house on the corner of Christopher and Hudson Street at Christmastime. This building's cornerstone, donated by Trinity Church, was laid in 1821. In 1891, St. Luke's officially became a chapel of Trinity Church. Given the proximity of the prison and St. Luke's and the later's ties to Trinity, Stanford and Upfold meeting would seem to have been inevitable, if not foreordained,

Right

Rev. George Upfold, Episcopal bishop of Indiana, previously had been

rector of St. Luke's and St. Thomas churches in NYC and knew the chaplain.

He laid out how Stanford

became prison chaplain: It was not until 1812-13, that his services were

regular and stated; though they had become quite extensive. In the former

year, he was chosen by the Inspectors of the State Prison, under the

authority of a recent Act of the Legislature, as the religious instructor

of the prisoners, at a very moderate salary; which appointment was renewed

annually, under every change in the Board of Inspectors -- such was the

confidence inspired by his capacity and fidelity -- until the removal of

the prison to Sing Sing in 1829.[viii] Prof.

Garber’s book provides a bit more detail: Concerned that language about reformation be

entirely lost from the conversation, [Newgate] inspectors suggested

offering an annual salary of $250 to a minister willing to contribute to

their effort to establish an orderly prison that could reform . . . . .[ix] Sommers' story of

Rev. Stanford's increasing involvement with the State Prison is also

detailed. …

Nicholas Roome, Esq. the head keeper of the prison, solicited him statedly

to devote a portion of his services to the benefit of that institution,

especially on the first Lord's Day in every month. This was the

commencement of his useful and long-continued labours within the walls of

the New-York State-Prison, where, for more than twenty years, he had the

immediate charge of the spiritual concerns of its inmates. . . . .[x]

At the April 24th, 1821 rites by which the modest little house of worship (formerly German Reformed) on Nassau St. became South Baptist Church, with Rev. Charles George Sommers as pastor, Stanford's role was to extend the hand of fellowship on behalf of the city's Baptist community. A friendship developed. Sommers preached from a bible given him by Stanford. The latter's widowed daughter became a member of that church and had her wedding held there when she remarried. The Stanfords turned to Sommers to edit their father's papers into a memior. Later he would serve as secretary of the American Tract Society and the American and Foreign Bible Society.

…

his duties [there] were a severe trial of his faith and patience; duties

from which most men would have often shrunk, for at times they were

attended with exposure to serious peril, from the contagious diseases

which were so frequently rife within its crowded and loathsome apartments.

. . . …the painful and responsible duty was frequently imposed upon him, of

visiting criminals under sentence of death.[xi] From

when the Rev. Stanford first began ministering to the public institutions

of NYC, until his death in 1834, about 10 Bridewell inmates were hanged in

compliance with death sentences ordered after their convictions on capital

charges: eight for murder, two for arson. My research finds references

to Rev. Stanford having ministerial contact with at least a half dozen

condemned prisoners who were executed: Ishmael Frasier (1816), Rose Butler

(1819), John Johnson (1824), James Reynolds (1825), Richard Johnson and

Catherine Cashiere (both 1829).

The above classic image of a condemned man in a cart, with his coffin and a minister, en route to the hanging in mid-18th Century London conveys the public ritual aspect of an execution. That aspect still adhered to its Americanized version in early 19th Century New York.

Their death sentences were commuted to life

imprisonment. He was unsuccessful in his efforts on behalf of yet another

condemned prisoner: Catherine Cashiere, a young woman of color, convicted

of murder. In

addition to being among the early pioneers in the production of religious

tracts in America, Stanford was in a unique position to become one of

early producers of gallows “true confessions” booklets, telling the story

of the condemned prisoners’ last days, minutes and seconds in this life.

These small books served multiple purposes: as cautionary tales, as

reports on the system, as a way to show his religious mission in action,

and as a means of augmenting his meager income.

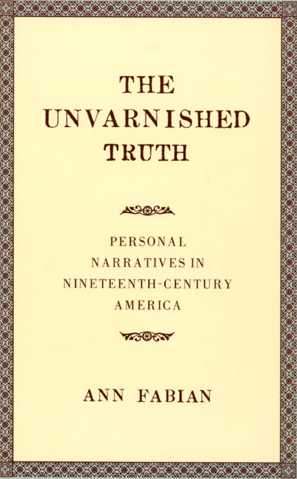

The Rutgers American Studies professor's book explores the cultural practice of selling the telling of one's woe for a price. It examines 19th Century stories by panhandlers, criminals, former slaves, POWs, and others. It probes print media exploitation of the public appetite for "tell-all" literature, including the "last words" of those condemned to death. Rev. Stanford was in a unique position bring those personal narratives to interested readers. Fabian devotes a half dozen pages of her book to the Bridewell chaplain dealing with Death Row inmates.

Instead

of pride and curiosity, Stanford carried piety, humility and prayer into

prison, and he carried out stories, arranging for the publication of

several criminal biographies and confessions

Although Stanford

traced his work among condemned prisoners back to the Puritan ministers

who had acknoweldged only the grace of God separated the worthy from the

unfortunates who stood on the gallows, his work was drawn into a

competitive market that places a monetary as well as a moral value on

criminal narratives.[xii]

Think

Dr. Phil doing his shows on early 19th Century death rows and

you get the picture. It could be argued that the TV show's sponsoring professional interventions benefit the persons revealing their sad situations on camera and that the revelations benefit the audience by making its members more in-sightful to such plights, as they may encounter or already have in their own lives. Still there are an obvious commercial implications as well. That

an individual inmate whose cause Rev. Stanford might champion could as

likely as not be a person of color, if happening today, would be accepted

as expected and unremarkable. We’d rightly say, “Why even mention it.”

When Rev. Nathaniel Paul, first pastor of Albany's Union Street Baptist Church, delivered his speech hailing NYS formally ending slavery, he spoke in terms striking similar to what Stanford wrote in his 1807 letter to NJ Gov. Bloomfield. Paul, born into a free black New Hampshire family (6 sons became Baptist ministers) declared:

"The progress of emancipation, though slow, is nevertheless certain . . . because that God who has made of one blood all nations of men, and who is said to be no respecter of persons, has so decreed; I therefore have no hesitation in declaring . . . that not only throughout the United States of America, but throughout every part of the habitable world where slavery exists, it will be abolished"

He

was five years into his stated chaplaincy at Newgate before the state

declared that all slaves born before July 4, 1799 would become free

effective 1827.

Those born after July 4, 1799 had already been declared

free but had to serve extended indentured servitude until 28 years of

page for males and 25 for females.

Slaves born before July 4, 1799 were

renamed indentured servants (still slaves in all but title).

Not until

July 4, 1827, could New York

African-Americans truly celebrate the legal end of slavery in

NY.

One

of the non-black NYers who also welcomed that historic moment was

Stanford. A voted member of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the

Abolition of Slavery, the preacher clearly held anti-slavery views and was

not adverse to sharing them with others; as in his 1807 letter to Gov.

Bloomfield: Organized in 1775 by mostly Quaker activists as the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, the association initially concentrated on cases of blacks and Indians claiming to have been illegally enslaved. In February 1784, the group enlarged its name to begin with the phrase "the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery" (PAS). It later added to its name "for improving the Condition of the African Race." Its leadership eventually included such prominent figures as Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush. The Society reached beyond its state borders to vote in as members such noteworthies as Rev. Stanford in NYC.

My

dear friend, you and I may never live to see it, yet I am confident that

everyone of the human family will eventually say, “I am born free.”[xiii] Indeed,

the chaplain was not adverse to sharing his views on a variety of concerns

with movers and shakers who could do something about the situations.

Sometimes he didn’t wait for them to act and instead acted on his own,

such as when early on (1807) he found deaf mutes in the

Alms-House. He immediately voiced the opnion that these too should “hear”

the Good News by being taught an alphabet so that they might see and read

it.

Eventually, a gathering of leading gentlemen met in his home to

establish a public institution of that nature.

It was held there in

recognization of his being the first in the city to initiate schooling for

the deaf.

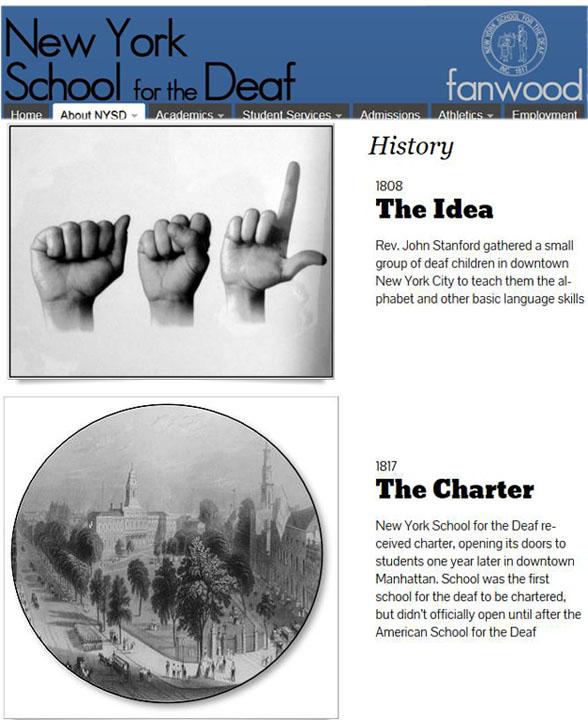

The outcome: the New York School for the Deaf set up in 1817.

Summers relates how in 1807 Stanford, distressed at the "deplorable condition of several deaf mutes" in the NY Almshouse, took action. "His first step was to form them into a class." He secured for them writing slates and an assistant to aid him in teaching them to write, using the principle of letting the hand substitute for the tongue. While signing classes for the deaf had been held in Europe, it is believed this was a "first" in the U.S. Stanford also persistently promoted the school-for-the-deaf concept through letters to leading citizens and the press. He had the satisfaction of participating in the school's dedication ceremonies in 1829.

He

immediately moved to separate them from adults.

Many whom the courts

sentenced there had only weeks previous been free roaming the city’s

streets, vagant youths without any school or home supervision.

That they

might not be behind prison walls, had they received some such care

and guidance, was obvious to him.

So the reverend voiced those concerns to

prison and charity authorities, wrote letters to the newspapers, and

finally and formally petititioned the Common Council (aka mayor and

aldermen) Feb. 13, 1812. Stanford

presented a detailed plan for a house or an asylum for vagrant

youth to receive supervision, care, instruction, and when old enough and

sufficiently job ready, employment placement outside. Not wanting for to

wait for buildings to be constructed for the purpose, he suggested using a

vacant structure as an interim refuge.

Just as Rev. Stanford had suggested, an existing public building decommissioned from its orginal use was put into service as the first NY House of Refuge for the reformation of JDs and shelter for vagrant youths in 1825. The converted ex-armory continued as a young offenders/youth-at-risk asylum until 1839 when the operation moved to a site bounded by 23rd and 24th streets, 1st Ave. and Avenue A, formerly Bellevue Fever Hospital. It moved to Randall's Island in facilities completed in 1854. The New York House of Refuge, the first juvenile reformatory in the nation's history, closed in 1935.

In recognition of his role as the institution’s

initial advocate, Rev. Stanford was designated to perform the religious

services at the inaugration ceremonies. In

his petition for a House of Refuge, Stanford called for including in its

curriculum some classes in seamanship for those students considered most

likely to benefit from such instruction: .

. . those who are capable of sea-service should be taught the rudiments

of navigation. This would enhance the value of the institution and promote

the benefit of our commerce.[xiv]

His

1812 advocacy of nautical instruction for JDs was echoed in an 1867 House

of Refuge annual report: The

idea has long been a favorite one with some of our members that a ship of

discipline and instruction would, under proper regulations, form a

valuable adjunct to the House ofRefuge.[xv]

*** Quite

aside from the interesting but somewhat esoteric issue of “first

chaplaincy” status, research into Rev. Stanford’s career yields

fascinating detail about life and death in early 19th Century New York. A

look back at him is instructive in that it shows how, despite being part

of and beholden to “the system” of his day, this sincere and committed man

of God was, nevertheless, enlivened by his faith to zealously seek to

improve, ameliorate and even reform that same system. Movie scripts by

skeptics often cast the prison chaplain as readily accepting conditions

around him, coldly indifferent or oblivious to inmate needs, immersed in

his scripture readings, an irrelevant figure not seeking to make the Good

News of that Good Book come alive in the here and now as well as in the

life to come. “The late chaplain to the humane and criminal institutions

in the city of New-York” was no such passive parson, if there ever were

any. ### |