|

Raymond Street Jail Was Scene of Last Hanging Execution in New York State 120 Years Ago December 6th [Part 1 of 2]

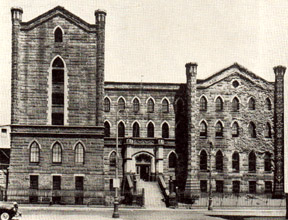

Raymond St. Jail that closed July 20, 1963. Photo from Page 36 of NYC Dept. of Correction 1956 annual report. (NEW YORK, 2009) -- One hundred twenty years ago the last legal execution by hanging in this state took place at Brooklyn's Raymond Street Jail. That hanging -- on December 6th, 1889, of John Greenwall, 30, (aka John Greenwald and Johann Theodore Wild), a tailor by trade, convicted in a 1887 burglary murder -- came the day after the last hanging execution in New York City/ County (Manhattan): that of Henry "Handsome Harry" Carlton, 27, in The Tombs. Carlton had been convicted of killing a policeman responding to an assault Oct. 28, 1888. |

A gibbet -- perhaps similar to the example shown above from Genesee County, N.Y. -- apparently was employed in hanging executions at Brooklyn's Raymond Street Jail and NYC's Tombs. Such a device was operated by using a counter weight, which when released, caused the rope to pull the noosed condemned criminal up with such sudden force as to break the neck (if done correctly). When done incorrectly -- as in the 1884 execution of Alexander Jefferson at the Raymond St. Jail -- the neck did not break, the condemned man slowly strangled to death. His agonized sounds and violent motions turned what was meant to be a solemn event into a horror show. Such occurrences prompted authorities to seek a more humane method. They were persuaded the electric chair fit that purpose. |

|||||||||

|

However, a committee was authorized to decide which form of electricity to use -- Alternating Current (AC) or Direct Current (DC). Legal maneuvers and industrial intrigues resulting from the commercial rivalry between Thomas Edison, wedded to DC technology, and George Westinghouse, tied to AC technology, delayed implementation of the law. Neither wanted "his" current linked in the public mind with electrocution. Meanwhile, counties continued conduct executions by hanging. That ended Aug. 6th, 1890, when the world's first electrical execution took place in Auburn Penitentiary with the electrocution of ax murderer William Kemmler. Greenwall was the ninth man executed at the Kings County Jail since it had opened on Raymond Street in 1838. The eight others were:

To set the backdrop scenery: Grover Cleveland was President. Victoria was still Queen. Leo XIII was Pope. David B. Hill from Elmira was Governor. The Mayor of NYC was Abram Stevens Hewitt, considered "Father of the New York City Subway System." Daniel D. Whitney was mayor of Brooklyn, then a separate city. The home team in major league baseball was the Brooklyn Grays. The Brooklyn Bridge was four years old and charging tolls to those using it. Begun in 1886, construction of the Institute envisioned by oilman Charles Pratt for the training of draftsmen and artisans was nearing completion and would open in the fall on Ryerson St. off DeKalb Ave., short walk easterly from the Raymond Street Jail.

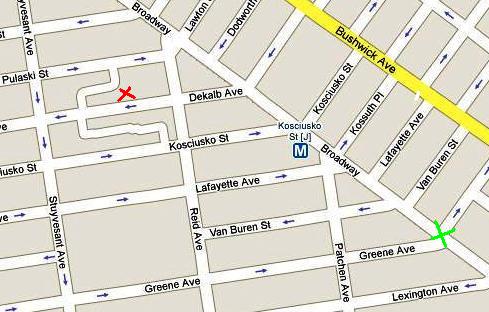

Situated on the north side of DeKalb between Reid Ave. (now Malcolm X Blvd.) and Stuyvesant Ave., it was one of 12 virtually identical frame, two-story and basement structures with long, high front stoops extending from the sidewalk. As a consequence, the basement windows were street level and accessible from the front yard adjacent to the stoop. The basement door was under the front stoop. The fierce cold wind about 12:30 a.m. March 15, 1887 may have extinguished the gaslight of nearest street lamp or, as occasionally happened in that era, perhaps the assigned lamplighter decided to skip doing some lamps in order to quit early and stay warm himself at home or in a saloon.

In the house were Mr. and Mrs. Weeks; their two sons, 9 and 4; Mrs. Week's mother, Mrs. Ellingham, visiting from North Adams, Mass., and a female servant. The Weeks had moved to the DeKalb address nine years earlier, about when their first son was born. Still awake, Mrs. Weeks thought she heard the sound of glass breaking and wondered if her mother may have dropped something and needed help. When she learned Mrs. Ellingham hadn't caused the breaking glass sound, Mrs. Weeks leaned over the second floor balustrade and listened carefully for sounds below. Though the burglar tried to proceed as quietly as he could collecting the family silverware and other items, he must have made sufficient sound to convince Mrs. Weeks that an intruder was in the house. She woke her husband and told him. Mr. Weeks, 36, was a powerfully-built, fearless fellow who never felt need to keep a gun in the house. In most any one-on-one contest, Weeks would have acquitted himself well. But the burglar whom he confronted in the dinning room, had a pistol and used it on the homeowner, shooting him through the heart. Mrs. Weeks went to the front window to scream for help and saw a stranger in her front yard make his way to the sidewalk and hurry away, walking briskly down the street. When neighbors responded, they found her prostrate across the bleeding body of her husband, who was sprawled partially under the dinning room table. One of the chairs had been broken in pieces as though Weeks had hurled it at the armed intruder.

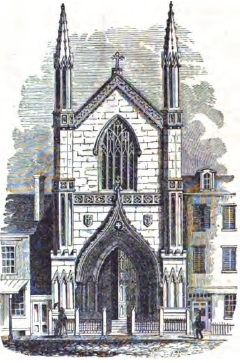

An informal inventory of items at the Weeks residence indicated the only missing articles were a silver pie knife and Mrs. Weeks' new spring coat (later found thrown on an ash pile at the end of the street). From about age 17, Lyman Weeks had been in the hat trade. At the time of his murder, he was a member of the senior staff at Hurlbut, Shethar & Sanford Inc., 548 Broadway, Manhattan. He came to the New York hat industry from Bridgeport, Conn. The family cemetery plot was located in Bridgewater, Conn. There on March 17, 1887, the interment took place after a burial prayer service attended by family members and representatives of the Hatters Association of New York. The day before, a large showing of hat tradesmen attended an afternoon memorial service in the Manhattan hatters district and later an evening prayer service at the Weeks home. It had been led by the Rev. W. J. Bridges of the Greene Avenue Presbyterian Church.

In 1866, they leased the ground at 548 Broadway, Manhattan, then occupied by Rev. Edwin Hubbel Chapin's Fourth Universalist Society Church of the Divine Unity. The firm erected on the site one of the largest stores ever devoted to the sale of hats. The building had a five-story front of white marble and arched windows. It was there that on July 12, 1887, the New York hat trade placed on display a black morocco leather-bound memorial book, with silver embossed lettering, dedicated to one of their own, the slain Lyman Smith Weeks. Charles D. Sanford was delegated to present it to the widow after some days of prominent display. Apparently not by casual happenstance did a young man named Lyman Smith Weeks with Bridgeport and Bridgewater, Conn., connections come to be working at a Sanford hat firm. The thread for that part of the tale seems traceable at least as far back as 1825 when Lyman Smith and John Sanford, both of Bridgewater, went into the mercantile business there together. Lyman Smith had two daughters. One, Betsey Ann, married a Smith R. Weeks. The other, Susan Adeline, married Charles H. Sanford. The Sanfords were in the hat making business. They had started in Bridgewater but later moved the manufacturing operations to Bridgeport. Charles H. Sanford continued living in Bridgewater while still overseeing hat making in Bridgeport. Little wonder Lyman Smith Weeks at age 17 began in the hat trade at Bridgeport and eventually became a senior staffer at a Sanford hat firm in Manhattan. On March 18th, Brooklyn Mayor Daniel D. Whitney announced that a reward of $2,500 was being posted for information leading to the detection and conviction of Mr. Weeks' killer. It was a huge sum in that era when, for example, 14th Pct. Commander Capt. Dunn's salary listed at about $2,400. The same day a subscription account was opened at the First National Bank of the City of Brooklyn for those who wished to contribute additional funds to increase the reward. At close of business, $375 had been added.

Two Brooklyn officers, Lowe and Hershaft who had been shot at by a suspected burglar in the 14th Precinct vicinity a few nights before the Weeks murder, went to Manhattan and identified him as their would-be assailant. Given his fitting the very sketchy description by Mrs. Weeks for the stranger exiting her front yard, he also became a possible suspect in that case well. Identified as Peter J. English, he was described at about 26, athletic build, about 170 lbs. But a few days later some serious credibility problems began to surface concerning the allegations and suspicions about English, whose name had transformed into Inglis. Several alibi witnesses stepped forward publicly to give sworn affidavits concerning his presence elsewhere at key dates and times in the police-promoted scenario starring the young man. These witnesses included members of the Margaret Mather dance company with which Inglis was a regular "super" or "supernumerary," what today is known as an "extra" in crowd scenes. For example, he would be one of the minuet dancers in a ball scene during "Romeo and Juliet." When the reform-minded and highly-regarded independent Justice James T. Kilbreth, after a hearing in the Jefferson Market Police Court March 21, threw out the Manhattan police officers shooting case charges against English/Inglis, Inspector Byrnes had the freed defendant immediately rearrested but refused to disclose the charges. Later that day, English/Inglis was held in Brooklyn on two indictments. One charged him with burglarizing the home of Charles Rumpf at 804 Jefferson Ave. March 9; the other charged him with attempting to shoot Officers Lowe and Hershaft, near the scene of that house burglary. In addition to those two indictments, DA James W. Ridgway had obtained a third from the Grand Jury whose foreman handed it up with the first two to Judge Henry A. Moore. Though that indictment remained sealed, the New York Times reported it charged English/Inglis with the Weeks murder. At the youth's Brooklyn appearance, reporters learned Inglis' age was 21 and that he had emigrated from Ireland five years earlier. Inglis claimed he had been in Philadelphia with the Mather dancers at the time the shooting incident involving Officers Lowe and Hershaft. Some unnamed law enforcement sources familiar with the Weeks investigation were quoted as expressing doubts about the youth's involvement in it and worries he might be "railroaded" for it if the actual killer didn't get caught.

Weeks' neighbors -- the Neely brothers David and Ralph and Dr. Tettemore -- testified about their responding to Mrs. Weeks' cries for help. Second District Coroner Dr. Joseph M. Creamer, whose brother Frank D. would years later become Kings County Sheriff, presented the autopsy results which also did not really add much to what was already known. The jury verdict was as expected: that Weeks died March 16th as the result of a pistol shot fired by a person unknown. On April 21, when English/Inglis' trial was due to start on charges of attempting to shot Brooklyn Officers Lowe and Hershaft, the Kings County DA told the Sessions Court that the prosecution was not ready to proceed. He asked for and received a postponement. One factor in that move may have been the presence at the court of several of the defendant's Mather dance colleagues ready to testify he was with them 100 miles away on the evening in question. Another factor may have been that Brooklyn law enforcement's real interest in him all along was as a suspect in the Weeks murder case but that this interest evaporated with the arrest some days earlier of John Greenwall as the homeowner's killer. Five days after Brooklyn Sessions Court granted the DA's request for postponement of the English/Inglis trial, the court -- seeing the prosecution still not ready to proceed -- granted the youth access to bail of $1,000, which was provided by bondsman John McGroaty, thus releasing the defendant from the Raymond St. Jail where he had been held without access to bail since his Brooklyn arraignment more than a month earlier. Thereafter the case against English/Inglis apparently faded away. It does not seem to have surfaced in newsprint again. On April 5, 1887, Greenwall, John Baker and Paul Krauss were arrested at Phoenix House, 52 Bowery. Along with Charles "Butch" Miller, then in the Tombs on an unrelated charge, they were accused of stealing on March 22 approximately 160 pieces of silverware, valued at $400, from the mansion of Jersey City's most powerful banker-politician, Edward Faitoute Condict Young. His huge estate on Glenwood Avenue eventually became the campus of St. Peter's College. When arrested, Greenwall was reportedly wearing banker Young's new hat also taken from the mansion, the thief having left his own in its place. According to police, on the night of his arrest for the Jersey City burglary, Krauss sent word from his cell that he had something important to tell Inspector Byrnes. He was brought to the Inspector's office where he made the claim that Greenwall had told him about killing Weeks. Baker was then also brought from his cell to Byrnes' office to back up Krauss' story and did so. The Krauss-Baker version had Miller as lookout and Greenwall the shooter in the Weeks burglary murder.

Later, Miller acknowledged he had been near the Weeks home to serve as lookout for the burglary but that Krauss -- not Greenwall -- broke into the house, that Krauss -- not Greenwall -- had the gun, and that Krauss -- not Greenwall -- was the one unable to sleep due to nightmares about his having killed Weeks.

In 1889, the same year Greenwall was executed, the Brooklyn Eagle began a series of articles attacking Dr. Jones, a pioneer in gynecological surgery. After she initiated a libel suit, the district attorney undertook a murder prosecution against her and her adult son, Charles, also a doctor. The trial judge directed an acquittal with regard to Charles and the jury itself acquitted Mary. However, she lost her libel suit, in part because many of the same traits that made her a skilled surgeon -- strong-minded, direct, professionally impersonal -- made her an unsympathetic plaintiff in the witness box. The criminal and civil trials drained the family's resources and she retired from medical practice but became an associate editor of a women's medical journal. Krauss had been drinking, according to Miller who said that this prompted him to express to Krauss concerns about going ahead with "the job" and that then the gun was shown by Krauss to demonstrate he was prepared for any situation which might develop. Miller claimed he told Krauss that he wanted no part of any gun play and that he was bowing out as lookout and did so, by going to a nearby saloon instead standing watch.

These competing versions of the Weeks burglary-murder -- that Krauss-Baker versus that of Miller -- made news print before the trial but Greenwall himself simply said he didn't know what happened since he wasn't there and didn't do it. At trial, his attorneys went with the Miller account while District Attorney Ridgway pushed the Krauss-Baxter version.

Justice Robert Earl, writing the Feb. 7, 1888 NYS Court of Appeals decision unanimously overturning the guilty verdict in Greenwall's first trail, succinctly summed up the prosecution and defense presentations:

. . . .It is undisputed that Mr. Weeks

was killed by a pistol-shot fired by some person who had burglariously entered

his house in the night-time. There was no witness who saw or heard the

shot fired, or was able to testify that the defendant was the person who fired

it, or that he was present in the house of Mr. Weeks on the night of the homicide.

The evidence on the part of the people [prosecution] to connect the defendant with

the crime, and to establish his guilt, was, in substance, as follows [arranged here as list items by NYCHS webmaster]:

On the part of the defense, evidence was given tending to throw some doubt

upon the identification of the defendant by the three witnesses called upon the

part of the people to show his presence near Mr. Weeks’ house on the night of

the homicide.

The defendant produced as a witness Charles Miller, who was

jointly indicted with him for the same murder, and he gave evidence tending

to show that the person who committed the crime was Paul Krause, and that

the defendant had no connection with it; and there was some other evidence

on the part of the defense, tending in some degree to show that Krause was

implicated in the crime.

Of the approximately 30 witnesses whom prosecution paraded before the jury at Greenwall's trial held May 16-20, 1887, in Sessions Court before Judge Moore, only a half dozen or so could be counted as crucial. Among these were, besides Krauss and Baker:

The number of witnesses presented by Greenwall's assigned attorneys, C. F. Kinsley and Edward McCall, were far fewer. They included:

The interesting aspect of Christian's testimony about the supposed Krauss' nightmare confession is not so much its being a reverse mirror image of Krauss' testimony about the supposed Greenwall's nightmare confession. In retrospect, what's more interesting is how DA Ridgway dealt with Christian as a potential witness before the trial. The DA interviewed the arrested burglar Christian in Inspector Campbell's office some days after the Greenwall-Miller indictment had been obtained based chiefly on the Krauss-Baker version of that night's events.

Thus the case for Miller and Greenwall being positioned outside the Weeks home for a burglary hinged on the reliability of Zora Chamberlain's claim to have seen the two twice, the second time coming hours after the first, the ferry ride. But even that testimony didn't point to which burglar entered the house and shot Weeks. DA Ridgway likely recognized that convicting Greenwall as the actual gunman was no sure thing. That could explain why he sought to bolster his case by introducing testimony about a prior crime never charged against the defendant. The DA's success in doing so at trial may have helped him secure the first degree murder conviction. But it also led the state's highest court, the Court of Appeals, to undo that guilty verdict unanimously. Writing with full concurrence of the other members of the high court, Justice Earl rejected Ridgway's appellate argument that the uncharged crime testimony -- even if found to have been introduced and admitted at trial in error -- was harmless, that it didn't prejudice the defendant, and therefore that it didn't constituted "a sufficient ground for reversing the judgment" -- that is, for overturning the guilty verdict and for erasing the subsequent sentence that Greenwall be hanged. Justice Earl didn't reject the DA's claim in a mercifully brief sentence or two, No, the DA had to endure the professional embarrassment of Justice Earl's delivering a step-by-step legal analysis, a sort of Collateral Evidence Law Lecture 101 checklist, setting forth the competency tests to apply to prior uncharged crime testimony and outlining how what Ridgway put before the jury failed to pass any of the tests. The written opinion's language was plain and unambiguous: The evidence . . . was therefore clearly incompetent. It was very damaging in its nature, and we cannot say that it did not have an important influence upon the minds of the jurors in reaching their verdict. The defendant's guilt was not so clearly established by other proof that it can be said that this evidence was harmless. It was objected to; the attention of the [trial] court and the district attorney was clearly called to its incompetency; and under such circumstances, we are of the opinion that the error of its reception cannot and ought not to be disregarded. A person on trial for his life is entitled to all the advantages the laws give him, and among them is the right to have his case submitted to an impartial jury upon competent evidence. The judgement should be reversed and a new trial granted. All concur. The particular testimony at issue was elicited from a former Greenwall employer, tailor George Mohring, who first appeared as a prosecution witness to contradict the defendant's claim he had never been to Brooklyn. Greenwall, brought back by his attorney, acknowledged he had worked at and lived with the Mohrings for a period of time in 1887. Then cross examined by Ridgway, the defendant was asked a series of questions related to whether he and Miller ever entered the Mohring home at 1 a.m. without permission after Greenwall had left Mohring's employ. Greenwall replied "No" to each of those questions. At this point, the settled law restricting the introduction of testimony on collateral issues warranted Ridgway switching to other matters but instead he chose to plunge ahead and to conduct what, in effect, was "a trial within the trial" on an uncharged crime. The DA recalled Mohring to the stand and drew from him testimony contradicting Greenwall's denials that Miller and he had ever entered his former employer's home at 1 a.m. without permission. The effect within the Weeks burglary-murder trial was to place Greenwall also on "trial" for reputedly breaking into Mohring's house, an uncharged and unrelated alleged crime the introduction of which was obviously prejudicial yet did not bear on whether Greenwall shot Weeks. Even with the Mohring burglary bolstering, the jury's deliberations lasted from 5 p.m. of May 19th, through the evening, resuming the morning of May 20th and continuing until 12:30 p.m. The jurors looked tired and dejected as they filed into the jury box. The foreman reportedly had tears in his eyes and was barely audible as he responded "Guilty" when asked the verdict. Trial Judge Moore volunteered for him, "Of murder in the first degree?" The foreman replied, "Of murder in the first degree." The next day editorial in the New York Times expressed shock that the jury deliberated as long as it did: "There was . . . evidence that leaves no doubt that Greenwall and Miller are the guilty persons. The only surprising thing is that there was difficulty on the part of two or three of the jurymen in making up of their minds." Contrast the closed-minded certitude of that editorialist, viewing the trial from his newspaper office desk, with the open-minded opinion of the Court of Appeals jurists who read the entire trial transcript: The defendant's guilt was not so clearly established by other proof that it can be said that this [Mohring burglary] evidence was harmless. " On May 27, 1887, Judge Moore asked Greenwall if he had anything to say before the sentence was pronounced. The defendant rose with tears in his eyes and declared: "I am innocent of the murder of Mr. Weeks. I don't know anything about his death. Mr. Ridgway has convicted me and if I am hanged, my blood will be on him and on Judge Moore and the jury." Judge Moore, who had permitted Ridgway to pursue the Mohring burglary/uncharged crime testimony, replied that he himself was "personally . . . entirely satisfied with the jury verdict." He then set July 15 for the hanging at the Raymond St. Jail. But that was stayed pending outcome of Greenwall's appeal of the conviction. That outcome, while overturning the first trial verdict, only delayed the execution.

| ||||||||||