Bowen Removal Warrants Own Research Project

How Townsend Cox, Thomas S. Brennan and Isaac H. Bailey came to constitute the PC&C board in Mercury's final year (1875) is especially fascinating because it involved such intricate political manipulations to purge that agency panel of any Havemeyer holdovers, including highly regarded James Bowen.

Here only an outline of the story can laid out. Much more archival digging would be necessary to unravel all the behind-the-scenes intrigues and the convoluted rationales advanced in the public arena to effect and justify the removal of Bowen, one of New York's most respected public servants. He had been PC&C president when its nautical school was launched in 1869. Indeed, he was credited as the program's initiator.

The story contains some dramtic elements: a surprise encounter with a notorious criminal in a penitentiary, a startling death scene, hints at toleration of corruption and nepotism, a show "investigation" and "inquiry" of sorts, the ordered dismissal from office and then the poetic irony: history nullifying that official verdict.

|

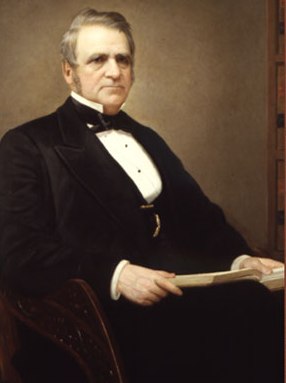

Judge Noah Davis

XXX |

Judge Noah Davis (above) presided over all three Tweed trials: - The first, in January 1873, ended in a hung jury.

- The second ended in a multi-count single misdemeanor fraud indictment conviction for which a felony sentence (12 years instead of the 1-year misdemeanor maximum) was imposed by Davis in November 1873 but overturned in June 1875 by the state's highest court as unlawful.

- The third, a civil court proceeding held in absentia under a special law targeting Tweed, ended in March 1876 with the ex-Boss found liable for $6 million owed to NY due to his frauds. Unable to satisfy the $3 million bail figure Judge Davis set in the civil case, Tweed had been placed in custody of the sheriff (not PC&C). He escaped Dec. 4, 1875 but was recaptured in Cuba and returned in late November 1876 to the sheriff's Ludlow St. Jail (image below) where he died in April 1878.

Legal scholars and historians have long debated whether Judge Davis exercised judicial impartiality in the Tweed cases and whether any basis in fact existed for the suspicion by some that Davis had been hand-picked by Samuel Tilden as the trial judge most likely to "get" Tweed. Conviction of the "Boss" was seen having value as an anti-corruption trophy to exhibit in the governor's Presidential campaign.

For more on Judge Davis, click his image above to access its source, a magazine article by former Tweed era mayor A. Oakey Hall in The Green Bag, January 1897 issues. A fast, interesting read mentioning Judge Davis is, via Google Books, Boss Tweed: the rise and fall of the corrupt pol who conceived the soul of modern New York by Kenneth D. Ackerman (Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005). For more on Ludlow St. Jail, click image below for Beauty and the Beast elsewhere on our website.

Use browser's "back" button to return here.

|

|

XXX

Ludlow St. Jail |

| Precisely where the tale ought to begin must await results from someone else's future researches. But a significant juncture surely was the April 3, 1874 visit to Blackwell's Island Penitentiary by Commissioner William Laimbeer, then PC&C president. He said the visit related to establishing a telegraph link with NYPD's 59th St. Precinct on Manhattan Island.

"To my great surprise I saw Mr. [William M. "Boss"] Tweed coming from the room furnished and occupied by him . . . . in which he receives his visitors," he told the board April 4th, according to the NYT next day story.

Tweed was in the penitentiary while appealing a 12-year sentence on conviction of multiple counts in a single misdemeanor indictment for fraud. Though assigned to the penitentuary hospital as an inmate orderly, so that his various physical ailments might be monitored, the room in question was not in the infirmary but within easy access.

Commissioner Laimbeer reported that he learned from Warden Joseph L. Liscomb and from fellow Commissioner Myer Stern that the latter had overseen the arrangements.

Claiming the room was "luxuriously furnished," unlocked and unguarded, Laimbeer moved for its immediate shutdown and for the chief phyician to check whether Tweed warranted hospital placement. Stern sought to table the motions until he had time to respond at the next meeting. Bowen backed tabling the Laimbeer motions.

The anti-Tweed journals waxed hotly indignant. Additional quotes from Laimbeer about the situation's potential for escape helped fuel their newsprint ire. Nothing if not zealous, Laimbeer visited Mayor Havemeyer at City Hall to place the matter before His Honor April 6.

The NYT next day reported Havemeyer commented he wanted "to hear the other side" and that he didn't see as necessary that Tweed's place of confinement be a cell, but wherever confined, it be secure and that the disgraced pol not roam the island. The mayor didn't see as necessary that every prisoner be put to work breaking stones but that work suitable for an inmate's intellect and training could serve as well.

Havemeyer did express himself mystified that Bowen voted with Stern and not Laimbeer in the matter. He considered that a conundrum which would be solved in time; he was disposed to wait patiently.

The mayor did not have long to wait to see, between Bowen and Laimbeer, a difference in the way each approached the problem of Tweed quarters in the penitentiary. At a PC&C meeting April 9, as reported by the NYT the next day, Stern explained that the inmate's medically-certified ill health and his size made confining Tweed to a cramped cell and its narrow bed untenable.

Therefore, the Commissioner had him assigned to work in the prison as a hospital attendant and had a small room found for his quarters. Stern said it was not any better furnished than some cells in Kings County Penitentiary and Sing Sing that Laimbeer himself had admired as humane. In it, Tweed had a couple old floor rugs, no wallpaper but some white muslim on the walls to keep out the damp, and a shelf for some books.

A keeper took Tweed to his hospital job in the morning and escorted him back at night, locking him in. The room was so situated that Tweed would have to elude about two dozen keepers on duty at key points to get to an exit. Stern submitted his report with a proposed resolution for various measures to increase security in that section of prison, to which Bowen added another -- for an iron lattice, ceiling to floor, across the relevant corridor, with a gate.

Bowen's Bold Move Corners Laimbeer

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above and below are images -- respectively captioned "In the cell. Blackwell's Island Penitentiary" and "Prisoners' cells in the Penitentiary, Blackwell's Island" -- from "Chapter XVIII.

Life On Blackwell's Island —The Dregs Of A Great City — Where Criminals, Paupers, And Lunatics Are Cared For —A Convict's Daily Life — ' Drink's Our Curse'" in Darkness and daylight; or, Lights and shadows of New York life (Publisher A. D. Worthington & co., 1892).

Click an image to access its source page from Google Books' digital version of the NYC history classic.

Use browser's "back" button to return here.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

| Stern and Bowen voted in the affirmative; Laimbeer in the negative, contending that the additional security measures were an unnecessary expense and that enforcement of current rules would suffice, presumably that would mean shutting down the Tweed room and returning him to the general inmate population housing.

One can imagine Bowen casting a glance at Laimbeer, sizing up this fellow Republican who had just made himself -- in the course of five days -- a hero with the anti-Tweed press. Those newspaper reports had raised eyebrows about Bowen's voting to table Laimbeer's motions until Stern could tell his side. A conundrum, Havemeyer said.

Voting to send Tweed back into the general inmate population might lower the eyebrows raised at Bowen and solve Havemeyer's conundrum about his voting with Stern.

But even if the inmate happened to be named Tweed, Bowen was not about to condemn a sick, prematurely-old man to sleep on a cell cot that couldn't hold him.

So the retired brigadier general proposed a resolution that had the effect of telling Laimbeer to "put up or shut up."

The resolution was a simple sentence: "Resolved, that sleeping quarters for orderlies of the Penitentiary Hospital be provided within the hospital."

It meant Tweed and the other orderly working in the hospital would sleep there too.

It also meant that if Laimbeer voted "no," the latter's original hue-and-cry about security would seem to have been insincere and make his real intent seem an appeal to those secretly (or not so secretly) wishing physical suffering be inflicted on the prisoner. Some in our midst are always ready to bring back the rack and the whip. Bowen evidentally believed Laimbeer could not, would not allow himself to become one of them.

Laimbeer voted for Bowen's resolution but Stern voted against.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is an image of the cover a 1874 report of the NYC Board of Alderman containing the report critizing the financial management and record keeping of Public Charities and Correction.

Click the above image for Google Books' digital version of Commissioner of Accounts Lindsay Howe's 22-page report.

Below is an image of the cover of PC&C's vigorous 40-page reply, signed by Commissioners Laimbeer and Stern, charging Howe with "insinuations, misrepresentations of facts, suppressions and perversions of the truth, and systematic attempts to put an evil construction on all our acts, however innocent . . ."

Click the image below to access Google Books' digital version of the PC&C reply.

Without disagreeing with the PC&C reply's factual defense and explanations, Commissioner Bowen declined to sign it because of its "intemperate language." He wrote, "The conclusions of Mr. Howe are in many instances erroneous; but the errors which he has made cannot be refuted by charging him with misrepresentations of facts, suppressions and perversions of truth."

Bowen's brief note can be accessed on Page 40 of the PC&C reply.

Use browser's "back" button to return here.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

| Bowen's move was implicit rejection of Stern's special arrangements for the separate room -- away from the other inmates. The senior PC&C Commissioner had listened to Stern tell his side in which the health concern was stressed as paramount. Bowen also had listened to Laimbeer's protest in which the reduced security that the separate room posed was stressed even more than the appearance of favoritism in treatment.

Bowen's bold but seemingly simple stroke -- addressing the health concern, ending separation from other inmates, eliminating security concerns about the separate quarters -- calmed that particular controversy for a while.

Accounts Commissioner's Report & PC&C Reply

But another controvery was building up, not on Blackwell's Island but on Manhattan Island in the offices of PC&C, the Board of Aldermen and the Commissioners of Accounts.

Having been appointed by Mayor Havemeyer in March of 1873, the PC&C board of Laimbeer, Stern and Bowen found the agency's accounts poorly kept and out of balance. Informally in July of 1873 and formally in early September of 1873, the board requested -- by transmitted resolutions and official personal visits -- the Commissioners of Accounts' assistance in straigtening out the mess.

Only in January of 1874, did Commissioner of Accounts Lindsay Howe begin a partial or preliminary investigation. On June 4th, the probe became official with a resolution adopted by the Board of Aldermen.

A highly critical report was issued on Sept. 3rd by Howe, implying the PC&C Commissioners had been unaware of the problems with the agency accounts and had sought to delay the investigation.

Commissioners Stern and Laimbeer issued a scorching reply.

It seethed with indignation over Howe's withholding from his report that about six months prior to beginning his examination of the books, PC&C had repeatedly sought the Accounts Commissioners' aid in resolving problems with them.

The opening paragraphs of their reply, addressed to an Aldermanic committee, castigated the attitude of mind they said his report reflected:

|

. . . . we beg to call the attention of your Committee to the animus which plainly characterizes the report of the Commissioner [Howe].

It is clear, from a casual perusal of the report, that the Commissioner is not actuated by that fair and impartial spirit . . .

. . . many things capable of a complete, and satisfactory, and thorough explanation— which explanation we would have cheerfully afforded the Commissioner, if he had requested us to do so—have been placed before your Honorable Board, and held up before the public as proofs of intentional wrong and violation of law, and even of possible corruption.

. . . . he appears to have proceeded in his investigation with the idea that it was his duty, in no instance, to give the members of our Board the credit of good motives, and pure and honest intentions in the management of the affairs of the Department, where it was possible to throw upon our conduct and actions, by a construction however improbable and forced, the suspicion of wrong and of intentional violation of duty.

. . . . the report of Mr. Commissioner Howe seems intended to make a sensation, at whatever expense to our good names, rather than to serve the interests of justice or the public good.

|

Stern and Laimbeer's joint reply engaged in a point-by-point refutation of the imputations in Howe's report. After the reply explained individual accounting items and issues by providing their particular historical and operational contexts, the two Commissioners concluded:

|

We have now, in all frankness and candor, answered the charges contained in Mr. Howe's report. We naturally supposed, but it seems most erroneously, that the Commissioners of Accounts would be able, ready, and willing to assist us in putting into proper order the account-books of the Department, which we found in an unsatisfactory condition upon our entrance into office.

But Mr. Howe seems to have conceived it to be his duty to spend the six months he has been about his so-called investigation in trying to discover by insinuations, misrepresentations of facts, suppressions and perversions of the truth, and systematic attempts to put an evil construction on all our acts, however innocent—how he can best serve, not the public interests, but the selfish purposes of those with whom he is now connected. . . . .

|

Bowen did not sign the reply. While conveying that he too found many conclusions in Howe's report to be erroneous, the retired general argued that refutation of those errors would not be well served by resort to counter-charges and intemperate rhetoric:

|

The undersigned, one of the Commissioners of Public Charities and Correction, respectfully begs leave to state his reason for withholding his signature from the report of his colleagues herewith submitted.

He cannot subscribe to the intemperate language of the report in respect to Mr. Howe's strictures on the administration of the Department. The conclusions of Mr. Howe are in many instances erroneous ; but the errors which he has made cannot be refuted by charging him with misrepresentations of facts, suppressions and perversions of truth.

The undersigned fully accords to Mr. Howe what he claims for himself — that he has in all faithfulness endeavored to discharge his duty without much regard to consequences.

|

The official inquiry and the sensationalized press reportage and commentary focused principally on alledged transactions involving Sterm and Laimbeer, individually or together [See NYT 9/11/74 and 9/14/1874 edits].

Bowen reportedly had argued against the Commissioners individually getting themselves directly involved in day-to-day purchasing matters, instead of sticking to the supervisory role of board members reviewing the work of purchasing staff. A Sept. 9th NY story stated:

|

A Times reporter made an investigation yesterday . . . also learned, on what he considers reliable authority, that two of the Commissioners of Charities were ready to reply to Mr. Howe's report, but that the third member of the board positively reused to attach his signature to the document.

This gentleman, it is well known, has not taken any part in the purchase of supplies for the various institutions under their charge, and he does not, therefore, desire either to indorse or refute the charges now made against the department.

|

A Sept. 23rd NYT story on a Grand Jury inquiry into the situation said:

|

Gen. Bowen, one of the Commissioners, was before them, and, it is said, he testified that he protested against the illegal purchases made by his colleagues, but was on all occasions outvoted.

|

No charges emerged from the Grand Jury inquiry.

PC&C Probe Context: Kelly Vs. Havemeyer

|

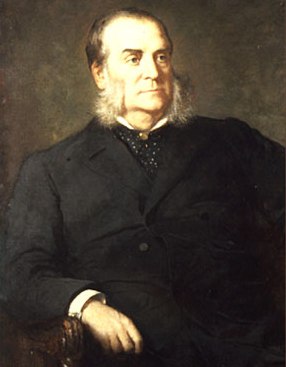

Boss John Kelly

XXX |

|

Above is an image of so-called "Honest" John Kelly from the page facing the title page of a most favorable (if not outright idolatrous) 1885 biography The life and times of John Kelly: tribune of the people by James Fairfax McLaughlin

Click an image to access from Google Books' digital version. Use browser's "back" button to return here.

Below is an illustration of the title subject from Page 72 of the totally denunciatory 1876 bio Samuel J. Tilden unmasked! by Benjamin E. Buckman. Click an image to access from Google Books' digital version of the book's Chapter Xi. Tilden In Partnership With Tweed.

Use browser's "back" button to return here.

|

|

XXX

Samuel J. Tilden |

| The details of the sundry imputations against Stern and Laimbeer, though intriguing, reside mostly in the historical territory of "Kelly vs. Havemeyer," the epic municipal power struggle between the aging, three-time mayor and the emerging new political boss, so-called "Honest" John Kelly.

Because that historical landscape lies beyond the boundaries of recounting Mercury's history, only a brief allusion will be made for the purposes of providing context to the Howe audit of PC&C.

While his report, and newspaper reports sparked by it, referred to PC&C purchases from vendors and agents whose firms included Laimbeer or Stern blood relations or in-laws, what drew even more interest were cited purchases from Havemeyer kith and kin.

The independence and eccentricities of the old mayor in his dealings with the Board of Aldermen had generated disputes that resulted in a petition drive asking the governor to remove Havemeyer from office. Leaders in that campaign included Boss John Kelly and wannabe mayor William H. Wickham. Gov. Dix censured the mayor on some specifics but did not remove him.

On the eve of a state Democrat convention at which Samuel J. Tilden was seeking the gubernatorial nomination, campaigning in part on his claim of having been anti-Boss Tweed, Havemeyer publicly aired charges against Tilden's No. 1 backer at that time, Kelly.

The mayor, who considered "Honest John" worse than Tweed (because the latter at least had made no pretense at virtue), charged Tammany's new boss with having committed an $88,000+ fraud upon the city treasury as sheriff.

Kelly sued for libel. On the day the mayor was to give a deposition in the case, Monday, Nov. 30, 1874, Havemeyer suffered an apparent apopletic stroke in his City Hall office and died.

An excellent overview of William F. Havemeyer's life, his 1874 controversies, and his sudden death is provided by the Daily Tribune's 12/1/1874

obituary (PDF format) found on the website of the New York State Council for the Social Studies and New York State Social Studies Supervisors Association.

How Tweed 'Helped' Extricate Laimbeer

Two unrelated developments within two days of each other in early December 1874 provided an opening for Laimbeer to extricate himself from the Howe audit mess under cover of protesting the "escape-risky" special arrangements of Tweed's confinement:

- the ascendancy of Republican Samuel B. H. Vance, president of the Board of Aldermen, to the role of Mayor-for-a-Month in the wake of William F. Havemeyer's sudden death, and

- the widely-circulated but false report of Tweed's escape from Blackwell's Island.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The Blackwell's Island images -- above (Penitentiary) and below (the warden's on-island residence and the island's Episcopal Church) and the following text excerpts -- are from Pages 456 through 460 in Moses King's handbook of New York city: an outline history and description of the American metropolis (1892).

Blackwell's Island, purchased by the city in 1828, for $50,000, is a long, narrow island in the East River, extending northward 1 1/2 miles, from opposite East 5Oth Street to East 84th Street, and containing about 120 acres. It is the principal one of the group of islands upon which are most of the public reformatory and correctional and many of the charitable institutions . . . . They have all been erected by convict labor, as was also the sea-wall surrounding the island. . . .

The Penitentiary on Blackwell's Island is a stone building, 600 feet long, with a long projecting wing on the north. The main building was erected in 1832, and the northern wing in 1858. The material used in its construction was the grey stone from the island quarries. It is four stories in height, castellated in design, and contains 800 cells, arranged back to back, in tiers, in the center of the building. A broad area runs entirely around each block of cells; and each tier is reached by a corridor.

Persons convicted of misdemeanors are confined here, and the number of prisoners averages nearly 1,000 a day. Over 3,000 offenders are received yearly, of whom 400 are women. Persons convicted of misdemeanors are confined here, and the number of prisoners averages nearly 1,000 a day. Over 3,000 offenders are received yearly, of whom 400 are women.

Each of the cells bears a card, giving the inmate's name, age, crime, date of conviction, term of sentence, and religion. All inmates are compelled to follow some trade or occupation. Stone-cutting in the quarries on the island, and mason-work on the buildings which the city is constantly erecting, furnish employment to a large number ; others are employed in the rough work of the Department of Public Charities and Correction ; and still others work at the various trades which they followed before their incarceration. Most of the women prisoners are employed in sewing, or as cleaners in the female department.

Each cell contains two canvas bunks, and all are kept freshly whitewashed and scrupulously clean. Solitary confinement is not practiced, except as a punishment for insubordination; and in spite of the fact that the inmates of the Penitentiary are to be seen at work all day in various parts of the island, and with a seemingly insufficient guard, escapes are almost unknown, only one prisoner having got away in ten years.

This immunity from escapes is due to the exceptionally strong natural safeguards afforded by the insular position of the institution, and the tremendously swift flow of the tide in the river, which makes it possible to guard nearly 1,000 criminals with fewer than 20 guards and about 35 keepers. . . . . This immunity from escapes is due to the exceptionally strong natural safeguards afforded by the insular position of the institution, and the tremendously swift flow of the tide in the river, which makes it possible to guard nearly 1,000 criminals with fewer than 20 guards and about 35 keepers. . . . .

As early as 1796 the Legislature provided for two State prisons, one at Albany, and one in New York City. The first Newgate Prison, in Greenwich Village, was opened in 1797, but it soon became crowded, and in 1816 the Penitentiary was built, on the East River shore at Bellevue. In 1848 the Bellevue grounds were divided, and the convicts were removed to Blackwell's Island.

Click an image to access from Google Books' digital version. Use browser's "back" button to return here.

|

| Of course, Commissioner Laimbeer conceivably might not have had Howe's charges in mind when he tendered his resignation Dec. 3, 1874 from PC&C.

The possibility exists that he was solely motivated by his exasperation at the "liberties" Tweed was seemingly allowed despite Laimbeer's efforts to curtail them.

His resignation letter, according to the next day NYT story, detailed how, the previous day while investigating the false report of Tweed's escape, he found the ex-Boss at Warden Liscomb's home on Blackwell's Island at 9 p.m. when the inmate should have been in the Penitentiary.

But the letter omitted the warden's explanation which Liscomb gave Laimbeer that evening and which the warden repeated in his own letter Dec. 7, responding to a Dec. 5 inquiry by Commissioner Bowen.

According to the NYT of Dec. 11, Liscomb wrote that he taken Tweed to Manhattan in response to a court writ, then to the inmate's doctor when the prisoner became ill and to the druggist to have the doctor's prescription filled.

Upon return with Tweed to the Penitentiary, the warden was surprised to learn that Commissioners Laimbeer and Bowen had been on Blackwell's Island checking on a report that the ex-Boss had escaped. This news greatly disturbed Tweed who, despite his medication, kept pacing about and complaining he couldn't breathe.

Liscomb remembered that a former chief of medical staff had advised that a night air walk before retiring for the evening could help prevent an apopletic stroke in someone showing the signs of agitation and difficulty of breathing.

So Liscomb told the keeper to walk Tweed before lights-out and stop at the warden's house so the prisoner's condition could be observed.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

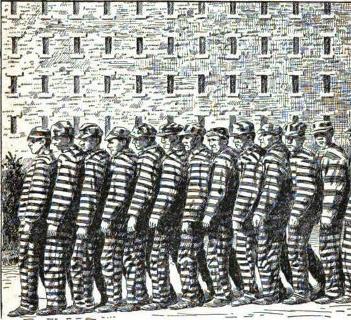

One of the issues raised in news reports in the wake of the Howe audit of PC&C involved "500 yards of striped prison cloth and 250 yards of plain prison cloth."

Presumably "stripe prison cloth" was the kind used in making inmate uniforms, such as seen in the above illustration of prisoners marching in lock-step.

The New York Times of Sept. 15, 1874 questioned how Quassaick Wollen Mill Company of Newburg, N.Y., came to supply $5,000 worth of such cloth under a Feb. 13, 1874 resolution "and that no opportunity was afforded to another manufactuerer to tender for the supply."

|

| That evening, when the keeper and Tweed appeared at the warden's residence, Liscomb saw that the inmate was exhausted.

Knowing the prisoner hadn't eaten since morning, the warden had Tweed brought into the kitchen for coffee and toast.

As the keeper was about return with the inmate, Laimbeer showed up at the warden's door.

This encounter was for Laimbeer supposedly the proverbial last straw, the final frustration, the outrage not be borne; thus his resignation.

That he seized on the incident to use to his own purpose may be unduly cynical.

That Vance or some other Republican in the Board of Aldermen leadership might have warned Laimbeer to get out, if he could, because the ax was about to fall and heads about to roll at PC&C may be dismissible as pure ex post facto speculation.

Coincidence may explain away that Laimbeer submitted his resignation Dec. 3, the same day Vance wrote the PC&C board, demanding an answer to the reports of extraordinary indulgences allowed Tweed which "if true in fact are cause sufficient for your removal from office," according to the same next day NYT story,

Tammany Hall apologist and occasional Assemblyman William C. Gover, in his pro-John Kelly "brief history of the Tammany Hall democracy from 1834 to the 1875," obviously disregarded Laimbeer's casting his PC&C resignation as a protest against Tweed's penitentiary accommodations. Rather, that regular organization partisan lumped Laimbeer's departure with the departure of Myer Stern as both resulting from the Howe audit allegations targeting the two of them:

|

. . . . . the serious and damaging charges of venality preferred against two of the Reform Commissioners of Charities and Correction . . . . hastened their removal . . . .

|

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is an image of the page from William C. Gover's book announcing the deliciously long title, subtitle and sub-subtitle:

TAMMANY HALL DEMOCRACY

OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK,

and the GENERAL COMMITTEE FOR 1875,

Being A Brief History Of

The Tammany Hall Democracy

From 1834 To The Present

Time,

With Brief Personal Sketches

Of The Prominent And Leading

Men

In The Tammany Hall General Committee.

A Resume Of The Vote In The Several States

In 1872, 1873 And 1874,

And The Vote In The City

In Reference To Governor,

Members Of Congress,

Members Of The

Legislature,

Mayor And Register, And Aldermen,

In November, 1874,

Carefully Prepared;

Which, With Other Political Facts

Regarding The Vote In The State For Governor

From 1822 To 1874

The Book Contains, Constitute

A Manual Or Hand Book

Of Reference Replete With

Information Of General Interest.

Respectfully Dedicated To The Democracy

Of The City Of

New York.

Click above image to access Google Books version. Use browser's "back" button to return. |

| Gover did not distinguish between the Stern "removal" via the late December Vance-Dix letters and the Laimbeer "resignation" via his early December letter.

To the John Kelly partisan, the two were examples of what discredited the Reform party and alliance that had brought about Havemeyer's administration.

To Gover, Howe's exposure of the pair's "venality" led to their "removal."

Vance's letter to the board cited letters by Gov. Dix and the late mayor, respectively Nov. 27th and Nov. 28th, expressing concerns about the alleged induligent treatment accorded Tweed.

The Laimbeer, Vance, Dix and Havemeyer letters were quoted, in whole or in part, by the NYT's Dec. 4, 1874 story.

On Dec. 8, "Mayor" Vance reappointed Lindsay Howe and George Bowlend as Commissioner of Accounts, both of whom Havemeyer had removed Nov. 12 without explanation as to cause.

If Havemeyer suspected them of being in league with those who had petitioned Gov. Dix for his removal as mayor, he didn't say, even when pressed to do so by the NYT reporter, according to the Nov. 13th story.

The NYT Dec. 9th story of their reappointment declared "Politicians who frequent the City Hall thought they saw in the change a precursor of wonderful things."

Whether those cited City Hall frequenters counted the subsequent removal of Bowen, along with Stern, at PC&C among the "wonderful things" that Howe's reappointment signaled is not known.

Known is the rationale advanced by the December mayor to justify removing Bowen: In effect, the retired general was guilty of not sufficiently supporting Laimbeer on issues involving Tweed's confinement arrangements.

Vance Claims: Bowen's Votes on Tweed 'Criminal'

Vance's Dec. 22nd letter to the governor, quoted in the NYT Christmas Day story, aknowledged

|

The Commissioner principally responsible for this criminal violation [the alleged Tweed confinement arrangements] is Mr. Myer Stern . . . .

The subject was repeatedly officially brought to the notice of Mr. Bowen but he omits to ascertain for himself the facts and remedy the matter complained of. He sustains by his vote and action Mr. Stern and I cannot relieve him from responsibility.

I consider the acts of both Commissioners were a criminal violation of duty on their part, for which they ought to be removed from duty. . . ."

|

To accept that rationale one must dismiss from mind the NYT stories (already cited) reporting Gen. Bowen made direct on-the-record inquiry of the warden concerning Tweed circumstances, his visiting Blackwell's Island in that connection, and his voting with Laimbeer on a number of Tweed resolutions.

Boiled down, Vance's letter seemed to suggest that not voting for all or nearly all of Laimbeer's proposed resolutions on Tweed constituted criminality on the part of Commissioner Bowen.

Interestingly, according to the 12/26/1874 NYT, the three new PC&C Commissioners appointed by Vance were escorted around the agency's office at 3rd Ave, and 12th St. on Christmas Day by Laimbeer who had resigned Dec. 3.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

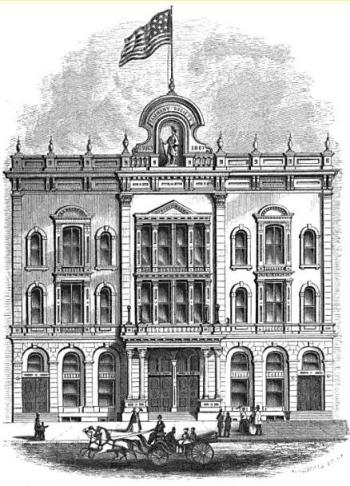

The above image of Tammany Hall on East 14th St. is based on one of the photos in the National Park Service Historic American Buildings Survey collection.

The Tammany Society, or Society of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was formed May 13th, 1789, soon after the inauguration of George Washington. The name came from a holy Delaware chief said to have been a lover of liberty and signer of the treaty with William Penn. The society began as a patriotic organization headed by a Grand Sachem and 13 lesser sachems, correspondinhg to President and the governors of the 13 original states.

Eventually members' political activities outside of Tammany, chiefly on behalf of Jefferson's party, crept increasingly inside until they dominated its character.

While not yet political per se, the society met in various locations, mostly taverns. Once decidely political, the organization met regularly at Martling's Long Room, at the southeast corner of Nassau and Spruce streets.

In 1811/12, the Tammany organization moved its headquaters a block north, at Nassau and Frankfort Sts. where the Brooklyn Bridge ramp is now located.

In 1868/9, the Boss Tweed moved Tammany's headquarters to East 14th St. near Third Ave., where the Consolidated Edison building is now situated.

The last abode of Tammany Hall was built on East 17th St. at Union Square East in 1928/29. In 1943 it was sold to to the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. It is now home to the New York Film Academy.

Tammany has long since ceased to exist as a separate political entity but the term "Tammany" is still used as journalistic short-hand for the NY County Democratic Committee; that is, the regular Democratic organization.

Below are two illustrations: one, the 'old" hall at Nassau & Franfort; the other, the "new" E. 14th hall design.

Botht appeared in the book published by Tammany to celebrate the cornerstone laying July 4th, 1867 for the new hall on E. 14th.

Click either illustration below or the photo above to access that volume entitled, in part, "Proceedings of the Tammany society, or Columbian order: on laying the cornerstone of their new hall in fourteenth street . . . ."

If you can tolerate the inflated rhetoric and discount the rigid partisan perspective, you may find the book contains considerable information about the organization and about NY history in which it was involved.

Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

|

Tammany Hall circa 1811/12

XXX

Design for "new" Tammany Hall, circa 1867-68.

|

| A NYT New Year's Eve story indicated that the new board, after meeting in Bailey's office Dec. 30th, acknowledged Tweed had actual "physical infirmities" to be taken into account in determining conditions of his confinement.

Nevertheless, the new Commissioners, expressing "a determination to extend no more favor to Tweed than they would to other prisoners," made an on-the-record point of issuing a formal order to Warden Liscomb to have the ex-Boss dressed in misdemeanor convict garb.

Vance may have sincerely felt that Tweed was the total embodiment of political evil to whom the ordinary considerations were not applicable and that any PC&C commissioner failing to demonstrate a like perception was criminally negligent.

Such moral indignation may help explain why Vance, a gas and lighting fixtures company executive, appeared untroubled by the separation-of-powers implications of his citing, as grounds for removal, Bowen's PC&C board votes on Tweed with which he disagreed.

PC&C commissioners did not serve at the pleasure of the mayor. They could be removed only for cause.

Each commissioner had wide discretion under law in deciding how to vote on a particular proposed resoultion.

No judicial finding had been rendered, or even sought, that Bowen had exercised that descretion in an arbitrary or capricious matter or that he violated any specific statute by any particular vote.

No court, judge or jury had found or even charged the Tweed hospital assignment and quarters constitued criminal violations of law.

The temporary mayor seemed dangerously close to claiming Bowen's "criminal violation of duty" arose from failure to vote the way that Vance considered was the only correct way to vote on Tweed.

Had Vance charged that Bowen's votes ran counter to the way the public viewed the matter and therefore had brought discredit to the agency and to the criminal justice system, the acting mayor would have been on stronger ground in terms of taking issue with Bowen.

But whether that would have been sufficient grounds for removal is another matter. Alleging "criminal violation of duty" may have been necessary to make the language of removal read technically sufficient.

Ironically, at the time the December mayor was publicly denouncing the "extraordinary facilities and indulgences" allowed "William M. Tweed, a prisoner on Blackwell's Island," and claiming Bowen had criminally violated his duty as PC&C Commissioner in that regard, the actual unlawfulness taking place was the ex-Boss' continued incarceration.

He should been released Nov. 22, according to a June 1875 unanimous decision of the state's highest court.

The Court of Appeals ruled trial Judge Noah Davis had imposed an unlawful felony sentence (12 years) on Tweed for his conviction under a multi-count misdemeanor indictment.

The order to run consecutively (or cumulatively) the 1-year sentence on each of the 12 counts for which he was sentenced was contrary to NY statute and precedent that establish a 1-year maximum on a misdemeanor indictment conviction, the top seven appellate justices held.

Some in the most virulent anti-Tweed faction of the municipal reform movement felt impelled to impugn the honesty and integrity of the court members for rendering such a ruling.

These outbursts came despite

- the fact that two of those seven jurists were Republicans (Charles J. Folger and Charles Andrews) and

- despite the fact that the lead opinion accompanying the ruling had been writen by one of the court's most learned judges (William Fitch Allen of Oswego), the justice with the longest and most varied experience in government and on the bench stretching back 30 years -- assemlyman, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District, State Supreme Court Justice, ex-officio Judge of the Court of Appeals, State Comptroller, and Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals since 1870

Even that arch-foe of Tweed, the New York Times (7/22/1875) could not endorse the attack on the court by Charles O'Connors, a key member of the prosecution team:

|

The presumption, however, is that the Judges of the Court of Appeals gave an honest decision.

If Mr. O'Connor, or anyone else, has proof that the Judges were corrupt or dishonest, why not send it to us? . . .

For our own parts, we cannot consent to accuse the Judges of the Court of Appeals of having "taken bribes" until conclusive evidence that they have done so has been placed in our hands.

|

Vance's Mysterious Unidentified 'Evidence'

But the acting mayor in December 1874 apparently felt no such constraint to impugn Myer Stern's integrity (as distinguished from the issue of good or poor judgment) concerning that PC&C Commissioner sanctioning special arrangements for Tweed's confinement after hearing the medical concerns expressed by the prisoner's physician and after seeing himself the inmate's apparent deteriorated condition.

Vance's letter to Dix read, in part:

|

I do not consider it necessary to determine whether these indulgences have been purchased by Tweed or whether they have been extended to him for other considerations.

I am, however, of the opinion, on a review of the evidence that Tweed pays for the privileges he is allowed.

Whatever the arrangements were which secured for Tweed these privileges, Mr. Stern was a party thereto.

|

|

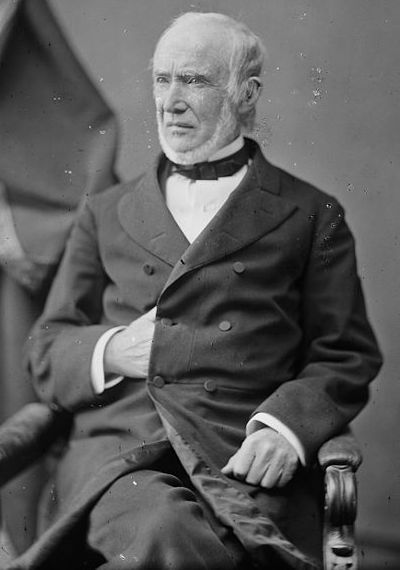

Charles O'Conor

XXX |

|

Above is a Library of Congress image of Charles O'Conor. The son of NYC writer, editor and publisher Thomas O'Connor, lawyer Charles modified the spelling of the family name to O'Conor so as to conform to the ancient usage.

At 16 he began to study law, and was admitted to practice in 1824 before age 21. In 1848 he became the Democratic candidate for lieutenant-governor of New York, but lost.

He sympathized with the southern states during the Civil War and became senior counsel for Jefferson Davis when he was indicted for treason.

O'Conor was a leader in the actions begun in the courts against William M. Tweed. A special government entity named by him the Bureau of Municipal Correction was established to smash the "Tweed Ring."

O'Conor is credited with drafting special laws for the purpose of prosecuting Tweed in civil as well as criminal courts.

He took strong exception to the state's highest court rulings in the Tweed cases and poured his scorn against the Court of Appeals into a book Peculation Triumphant, being the Record of a Five Years' Campaign against Official Malversation, A. D. 1871-1875 (New York, 1875).

He declined any compensation for his services in these cases.

Despite his declination, O'Conor was nominated for President in 1872 by a faction of the Democratic Party opposed to Horace Greeley. The attorney received no electoral votes. In the constitutional crisis resulting from the contested Presidential election of 1876, O'Conor was one of Tilden's attorneys arguing for his client's electoral vote claims and against those of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Under Republican-run Reconstruction, the GOP still held power in three Southern states and disqualified election returns they claimed had been produced by intimation and violence directed at Negroe voters. The Democrats denied this and countered such claims were being used as a excuse to produce a win for Hayes.

Click the photo of O'Conor to access Google Books' digital version of book Peculation Triumphant. Click the O'Conor sketch to access Google Books' digital version of the his bio in Appletons' Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Use browser's "back" button to return here.

|

| No criminal charges were ever filed based on the unidentified "evidence" claimed by Vance. He made no declaration of referring "evidence" to the grand jury or the district attorney. Nor did he actually say the undisclosed "evidence" showed Stern or anyone else was paid for sanctioning the accommodations.

Rather, Vance used the present tense of the verb to assert Tweed "pays" his way, a free-floating generalization about the ex-Boss' pattern of life to explain the accommodations.

In the lengthy portion of the Vance letter devoted to detailing certain transactions cited in the Howe audit, the entire focus was on Commissioner Stern. Bowen was not mentioned.

Nor was mentioned Bowen's opposition to the purchasing system entered into by Stern and Laimbeer. Indeed, Laimbeer's involvement with Stern was nowhere alluded to, not even indirectly.

Earlier in his one month as mayor, Vance had accepted Laimbeer's resignation that was framed as a protest against the Tweed accommodations. Near the end of his mayoral month, fellow Republican Vance named the then recently unsuccessful GOP Congressional candidate Isaac H. Bailey to fill the remainder of Laimbeer's term.

Vance invited William H. Wickham -- elected with the support of John Kelly's Tammany Hall and set to take over City Hall on Jan. 1 -- to nominate Stern and Bowen's replacements. The mayor-elect did so and the December mayor promptly appointed them: respectively Townsend Cox and Edward L. Donnelly.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The name -- A. R. Lawrence -- in the title page image above has been circled in red here for emphasis. Son of State Senator and City Controller John Lawrence, Abraham Riker Lawrence was appointed Assistant Corporation Counsel upon becoming a lawyer in 1853. A Tammany Haller, he became compiler of a 1859 City Council-published volume of NYS tax laws. Later he served as counsel to the Committee of 70 fighting Tammany Boss Tweed. In 1872, "Honest" John Kelly, picked him as new-look Tammany's mayoral candidate, proof of its reformation.

Lawrence lost to the reformers' own candidate, former Mayor Wm. F. Havemeyer. In the next election, Lawrence won a NYS Supreme Court seat. He served 28 years. In that capacity, Lawrence granted the 1874 writ

of habeas corpus enabling Tweed to take to the state's top court his claim of an unlawful felony sentence on his misdemeanor conviction.

Use your browser's "back" to return if you visit the Google Books version of his book.

|

| All three appointments were took place Christmas Eve 1874. None had any PC&C experience.

The 4 Were

Aware of

Tweed's

Prospects

for Release

by Court

of Appeals

Bear in mind that when Dix and Havemeyer in their late November 1874 letters and Vance and Lamimbeer in their Dec. 3 letters cited the Tweed accommodations issue, the foursome had to be already aware Tweed's continued penitentiary confinement was legally uncertain at best.

A passage in the chapter on Tweed's attorney, former Court of Appeals justice George Franklin Comstock in Great American Lawyers by William Draper Lewis

(Vol. 6, Publisher J.C. Winston, 1909),

provides the dates relevant in considering the timing of Laimbeer and Vance's letters:

|

Tweed was actually committed to the penitentiary

on Blackwell's Island on November 29th, 1873.

Having served the first term of one year [of the trial judge's sentence of twelve consecutive 1-year terms on the misdemeanor indictment conviction] and paid

one fine of two hundred and fifty dollars, upon a

petition verified December 14th, 1873, Tweed on

December 15th, 1874, obtained from Abraham R.

Lawrence, a Justice of the Supreme Court, a writ

of habeas corpus directed to Joseph L. Liscomb,

Warden of the penitentiary of the City of New York.

On December 17th, 1874, the warden produced

in court the body of Tweed and filed a return showing the time and cause of imprisonment. To this

return Tweed filed an answer. The proceedings

were then adjourned to December 22d, 1874 . . .

|

|

Judge Sanford Church

XXX |

|

A fact not easily gotten around undercut the efforts of those seeking factors -- other than the top court's nine judges' own understanding of the law in the Tweed case -- to account for their ordering his release.

That fact was the unanimous nature of the decision to invalidate trial Judge Noah Davis' sentence of felony time on a misdemeanor indictment conviction.

That unanimity included at least three who could hardly be considered hostile to Republican Davis, politically or personally.

Though a Democrat, Court of Appeals Judge Sanford Church (image above) and trial Judge Davis had been friends nearly 40 years, ever since they in their late teens had clerked together at the same Orleans County government office in Albion and later studied law together. From 1844 until about 1858 the two were law partners in that city. The partnership had to be dissolved when Davis ascended to the bench as a State Supreme Court Justice; the friendship was not dissolved.

The two Republicans on the top court bench joined the Tweed decision: Charles Andrews and Charles J. Folger (images below).

Folger had been a judge in Ontario County about a decade before election to the State Senate where he served also a decade before election to the top court in 1870. He had chaired the Judiciary Committee in the State Senate and in the Constitutional Convention of 1867.

He would be appointed Chief Judge in l880 to fill Chief Judge Church's vacancy but resigned the Chief Justiceship in 1881 to accept appointment as Secretary of U.S. Treasury.

Charles Andrews served as District Attorney of Onondaga County 1854-57, as mayor of Syracuse, 1861 & 1868; delegate to Constitutional Convention of 1867 and was elected Associate Judge of Court of Appeals, 1870. He would be appointed Chief Judge, 1881-82, to succeed Judge Folger.

Click any of the three Court of Appeals judges' images -- Church, Folger or Andrews -- to access their source, the very excellent website of the Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York where additional bio details can be found. The story of Democrat Church and Republican Davis' friendship can be found in the NYT obit on Judge Church May 15, 1880.

Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

|

Judge Charles J. Folger

XXX

Judge Charles Andrews

|

| That date, Dec. 22, 1874, on which the Tweed habeas corpus hearing was to take place, happened also to be the date that the temporary mayor sent his official request to the lamp-duck governor to remove Stern and Bowen from PC&C.

Dix complied the next day even as the newspapers carried the story about the previous day's Tweed habeas corpus proceedings in which the inmate's petition for release was (as expected) denied but his application to have the state's highest court hear his appeal of that denial was (as also expected) granted.

Surely, Dix and Vance's legal advisors had to have warned them in November, if not long before, not to assume the trial Judge Noah Davis' aggressive sentencing of Tweed to felony time on a misdemeanor indictment conviction would be sustained by the top court. They would have pointed out that Tweed had going for him both the weight of considerable legal precedent and ex-Court of Appeals Comstock's even more considerable credibility with members of the court. That seven of the nine justices were Democrats didn't hurt Tweed's chances either, but such a box score line-up wouldn't matter much if the decision handed down was unanimous [which it was].

So all Dix and Vance's activity demonstrating how tough on Tweed they were must be viewed agaist the background of their awareness that his continued penitentiary confinement stood a good chance of being declared unlawful. The anti-Tweed forces that had elected Dix, Havemeyer and Vance, among others, faced the strong prospect their legal strategy to have the ex-Boss do felony time on a misdeamor indictment was about to blow up in their faces.

Given these considerations, one need not be a cynic to ponder a question that a cynic certainly would pose: Was the end-of-year rush by the exiting state and city administrations to remove supposedly "soft on Tweed" Commissioners simply a big noisy and distracting show, all about keeping the villian behind cell bars, even while a defect in the anti-Tweed forces' legal strategy was poised to pop open a prison door through which he might lawfully walk out a free man?

But perhaps Bowen's class-act example regarding Howe's critical audit should be followed in assessing Dix and Vance's conduct. Ought not the lame-duck governor and one-month mayor be given what they would not give Bowen, who had given a decade of service on PC&C board -- the benefit of the doubt?

Could not Bowen's comment on the Howe report be paraphrased to "accord to" Mr. Dix and Mr. Vance what each would claim "for himself — that he ha[d] in all faithfulness endeavored to discharge his duty without much regard to consequences?"

Maybe they really did believe they were doing the righteous thing and that political expediency was not even considered. Or perhaps they, engaged in political warfare of their time, did not see the distinction that seems more discernable with the distance of history.

History Doesn't Echo

Dix-Vance Verdict

on Bowen

Without taking away anything from Dix and Vance's presumed honest intentions in publicly dismissing Bowen for what they declared "criminal violation of duty" with respect to Tweed's accommodations, history seems not to have echoed their verdict on the general, or at least appears not to have been eager to rebroadcast it.

The PC&C annual report for 1875, signed by Commissioners Bailey, Brennan and Cox, provided on Page 14 some particulars on their appointments and on Page 15 provided a chronological list of PC&C Commissioners from 1860. On both pages Bowen and Stern were said to have resigned. Not "removed," not "dismissed," but "resigned."

Had Bowen and Stern been permitted to submit their resignations just prior to the governor formally removing them? Or if the newspaper reported dismissals were real enough, were the annual report authors simply unwilling to write "dismissed" or "removed" next to any Commissioner's name, so "resigned" was used instead?

The insertion of the information came near the end of a short history of Blackwell's Island Charity Hospital.

In two other passages -- Pages 10 and 12 -- about Charity Hospital gains, Bowen was named among the Comissioners responsible for various hospital improvements at the times cited.

On Page 92 was the fifth mention of Bowen in the annual report for 1875, a year no day of which did he serve as Commissioner.

This 1875 annual report's last Bowen mention related to the Soldiers' Retreat on Ward's Island

|

THE SOLDIERS' RETEEAT.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is an image of Ward's Island Inebriate Asylum building, where an area not otherwise in use, was set up by Gen. Bowen for NYC's Civil War disabled veterans.

Click to access image source, "Hospitals of Olde New Yorke" on Nancy E Lutz's Brooklyn Genealogy Information Page.

Use your browser's "back" to return.

|

| This was established in 1869, during which year, General James Bowen began gathering together the disabled veterans of the late war, residents of New York City, and gave them quarters in the unoccupied portion of the Inebriate Asylum building.

During the past year a large proportion of these men have gained admission to National Soldiers' Homes, the majority going to Hampton, Va., and Dayton, Ohio.

By this means the city is relieved of an expense which is now borne, as it should be, by the general government.

Those ineligible for admission to National Homes, and able to work, have been discharged.

A few soldiers in the Retreat were too infirm to be sent away, and were consequently transferred to the Homoeopathic Hospital. . . . .

The last inmate was discharged or transferred, Dec. 14th, 1875, and the Soldiers' Retreat, as such, passed out of existence.

SELDEN H. TALCOTT, M.D.,

Chief of Staff:

|

The Page 15 list of PC&C Commissioners, with the red underline added here for emphasis, from 1860 read:

The Page 14 passage noted:

|

In 1873 there were 9,871 admissions. In the spring of this year the following gentlemen were appointed Commissioners, William Laimbeer, James Bowen and Myer Stern.

In 1874 there were 10,675 patients treated. In December of this year the Commissioners resigned, and Isaac H. Bailey, E. L. Donnelly and Townseud Cox, were appointed. . . . .

In 1875 there were 10,075 admissions. In January of this year Commissioner Donnelly resigned, and Thomas S. Brennan, Warden of Bellevue Hospital, was appointed to the vacancy.

|

Posthumous Bios, Obit Omit Mention

Omission of any mention of PC&C removal, dismissal or pressured resignation in posthumous biographies of Gen. Bowen can, of course, be attributed to the social custom to be laudatory and not to speak ill of the dead.

Still, had the Dix-Vance verdict on Bowen been viewed as the defining moment of his life, could its mention have been omitted? Arguably it was viewed as de minimis.

Not only did the NYT obit of Sept. 30, 1886 not mention Dix-Vance, it seemed deliberately intent on emphasizing Bowen's integrity, honesty and sense of honor. It recalled his Civil War role as Provost Marshal administering Union-held territory in five Gulf region rebel states:

|

The office was at that time one of unusual responsibility and its duties were discharged by Gen. Bowen in a manner that commanded admiration among the rebels as well as unionists.

There was every confidence in his integrity at a period when even the most loyal of men were distrusted.

|

The NYT obituary recounted how, after he had become PC&C Commmissioner, the state Legislature doubled the salary -- from $5,000 to $10,000. Calling the pay hike outrageous and unconscionable, Bowen refused to draw more than the original amount. His public protest and personal stance helped prompt the lawmakers to rescind the increase.

In case its readers hadn't gotten the message from the entire tenor of the Bowen obit, its closing sentences delivered in even clearer terms a verdict quite other than that written by Dix-Vance in the midst of anti-Tweed hysteria 12 years earlier. The Times said:

|

Gen. Bowen was a scrupulously honest man, and his fine sense of honor was happily supplemented by a genial disposition . . . In his unobtrusive way, Gen. Bowen was the dispenser of many benfits to others, and his death will touch a chord of sympathetic sorrow in many hearts throughout this broad land.

|

Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography, published by Appleton and Company, 1887-1889, edited by James Grant Wilson, John Fiske and Stanley L. Klos, noted:

|

His last public office was that of Commissioner of Charities, to which he was appointed by Mayor Havemeyer, and continued to fill most acceptably for many years.

|

Edward Harold Mott's generally favorable history of the Erie Railroad that Bowen had headed, Between the ocean and the lakes: the story of Erie,

published in 1899 by J.S. Collins, 1899, included bio notes on the key figures in its story.

Mott cites Bowen playing a leading role as PC&C Commissioner in launching at Bellevue the world's first municipal hospital ambulance service and in raising that hospital standards, performance and standing as medical care and teaching institution.

Upon hearing that a NY citizen in the 1800s had been a leading member of the Whig Party one might conjure the mental image of a rigid, narrow-viewed, backward-looking person.

On the contrary, Bowen -- like his friend and fellow former Whig-turned-Republican, Gov. Seward -- was among the most forward-looking and innovative social reformers on the New York scene, as his role at Bellevue and other PC&C medical institutions illustrated.

Testifying to this are passages in Mary Adelaide Nutting and Lavinia L. Dock's A History of Nursing: The Evolution of Nursing Systems from the Earliest Times to the Foundation of the First English and American Training Schools for Nurses published by G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1907, and accessible on Google Books as is Mott's Erie RR history.

|

That winter [January 1872] the [State Charities Aid Association's Bellevue Hospital Visiting Committee] investigation of the hospital conditions was carried on with the utmost thoroughness and conscientiousness.

By good fortune one of the Commissioners, General James Bowen, was not of the usual politician type, but a gentleman and personal friend of the visitors. He not only assisted them with official support, but begged them to carry their investigations into the other city institutions.

It was no doubt owing to the weight of his personal and civic prestige that the visitors were protected against the antagonism of the petty politicians which, in the Westchester poorhouse and many other institutions, had been freely displayed against them . . . .;

Only this one friend on the Board of Commissioners is recorded in the minutes of that institutional invasion, and on the Medical Board only four—Dr. James R. Wood, Dr. Austin Flint, Dr. Stephen Smith, and Dr. James M. Markoe. To these five men we owe the initiation of reforms in hospital service in New York.

The others were, if not actively in opposition, at least discouraging. One of the physicians and even a clergyman who visited Bellevue publicly expressed the opinion that the hospital was not a proper place for ladies to visit, and these criticisms illustrate the character of the stream of disapprobation—social, political, and medical—which the women had to confront during that momentous winter.

In a comparatively short time, with the strong support of General Bowen, the visitors succeeded in making substantial improvements in the kitchen, laundry, and supply departments . . . .

|

Bowen's Replacement Replaced After 14 Days

On Jan. 7, 1875, Boss John Kelly's fellow 18th A.D. committeeman, Thomas S. Brennan, who had been Bellevue Hospital warden, was sworn in for the unexpired balance of Bowen's term set to run to May 1, 1877, minus the 15 days or so that Wickham's first pick for the post, Edward L. Donnelly, served before resigning.

Donnelly, a good Tammany Haller and committeeman from the 13th A.D., may have been named simply as a place-holder, expecting to step aside once the real selection for Bowen seat was made.

Evidentally Donnelly, Tammany treasurer and Sachem, had no hard feelings about making way for Brennan. Four months after vacating his PC&C Commissionership, Donnelly was working side-by-side with the Boss and other Kelly men at Congress Hall during the battle over the Miller-Husted Charter bill for NYC.

Edward L. Donnelly, a liquor dealer on 9th Ave. had been nominated at the Sept. 16, 1858, state Democratic Convention in Syracuse to run for the office of state prison inspector [Sept. 17, 1858 NYT]. The top of that slate was Democratic gubernatorial candidate Judge A. J. Parker. Much of the ticket went down to defeat when Parker lost to Republican Edward Denison Morgan.

Donnelly was still in business on 9th Ave. five years later. A NYT 11/23/1863 story of Board of Aldermen proceedings Saturday, Nov. 21, 1863 showed Edward L. Donnelly gaining permission to set curb and gutter stones and flag a space four feet wide through the sidewalks in front of his premises on 65th St., between 9th and 10th avenues, at his own expense and under direction of the street commissioner.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is an image of the NYC Dept. of Public Charities steamer "Thomas S. Brennan" showing damage from a collision with a steamship "Maraval" May 25, 1908 while the "Brennan" was returning from ceremonies launching the agency's then new steamer named for one of the great ladies in the history of NY charities and correction, Josephine Shaw Lowell.

Brennan started in PC&C as a watchman (patrolman) at Bellevue, and over more than a decade advanced through the ranks to warden before becoming commissioner. After long service as PC&C Commissioner, he served as Street Cleaning (Sanitation) Commissioner and still later as a Dept. of Public Charities (Welfare) Commissioner.

Click image to access the Public Charities Department 1908 annual report's account of the collision. Other images appear in the Google Books version. Use your browser's "back" to return.

|

| The choice of Brennan for the Bowen seat installed on the board someone having a measure of administrative experience in, and hands-on knowledge of the agency's operations. Bailey was a leather good merchant; Townsend Cox, a member of the stock exchange.

Brennan, son of a coal merchant, had graduated St. Therese College, near Montreal, at age 16 and became a watchman at Bellevue Hospital, quickly advancing to captain of the watchmen. There followed promotions to night store keeper, clerk, steward, deputy warden and in 1866 warden. He played a significant role in the development and introduction of ambulance servce, the facture bed and head rest at Bellevue. As its warden, Brennan also had charge its reception hospitals.

|