TO MY CHURCH

. . . . Before his visit to the United States in September 1987, our Christian community at Rikers had written to Pope John Paul II. This came about entirely through the initiative of the inmates themselves. It was worth seeing -- the care that was taken, the discussions involved in composing that letter full of respect and hope, reaching out to a living center in a society that is visible, but so often immobile. It was a beautiful letter. (It made me think of Augustine's expression: "There is a sign by which one may know whether a man or woman possesses the Holy Spirit. It is that he or she loves the church.") Some of the inmates even wrote to the upstate prisons to ask for signatures. They came by the hundreds. Some time later we received a written message of thanks through the archdiocese. (One inmate said to me, "A letter is a flower in the desert." Then he added, "A visit is a fountain.") . . . .

| Origins of Abraham House where author Fr. Raphael is spiritual director.

Above: Logo sketch from

Abraham House newsletter.Below: Images and text excerpts from Fall/Winter 2002 newsletter.

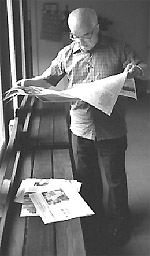

This man and his friends had

the idea for Abraham House

Above: The place where the idea took root: The

Rikers chapel, decorated by prisoners, was

the spot where Wash, Sr. Simone and the

other founders began to dream.

James Washington was a correction officer at the Rikers Island prison 23 years ago when he first knew Sr. Simone and Fr. Peter.

He had been raised in South Carolina and had taken part in

the dangerous civil rights marches organized by the Rev. Martin Luther King.

"Wash" brought extraordinary humanity to the worst Rikers cellblocks. . . .

He and two co-workers,

Willie Sutton and Robert Jones, had a dream, like King, and it was motivated by the same concern for justice.

They wanted to give poor people a chance, and they recognized what had landed some inmates in

prison was not always their fault.

Twice a week these Rikers officers began brain-storming with Fr. Peter and Sr. Simone about setting up a novel rehabilitation program, the one that ultimately became Abraham House.

Soon the prison warden noticed the Catholic chapel was being painted more and

more frequently.

Wash brought his crew of prison painters to the chapel often so

that discussions could continue. And his insistence and encouragement played a significant

role in Abraham House becoming a reality and moving to the Bronx.

Indeed, he helped us load the U-Haul that May morning in Brooklyn and when the Bishop who was driving our van (Bishop Andre du Puy) became lost in the South Bronx streets, Wash took

over. Mott Haven was familiar to him . . . .

He and his wife Maxine spent the first years of their marriage in a ground-floor apartment in the projects across the street from the brownstone that would become Abraham House. . . .

Wash is now a cancer patient, in and out of the hospital. He still is dreaming on

our behalf, and attentive to the work being done at AH.

Abraham House is located at 342 Willis Avenue in the South Bronx.

Reflecting on the Past...

Considering the Future

by Fr. Peter Raphael

A new chaplain in a prison is on probation; it takes time -- a lot of it -- to be accepted, both by the officers and the incarcerated.

The retreats that we organized for prisoners at Rikers Island in the 1980s were a beginning.

These were precious days, heavy with meaning. The staff noticed the change they effected. . . .

Even the Commissioner of the Department of Correction became convinced that following a retreat, tensions in the cellblocks eased for a period of time.

Christmas 1989 -- 10 years after my first Mass in the prison -- was another turning point. Some 250 inmates filled the chapel that night, celebrating the feast in prayer and song. In prison you rarely have a full church. The staff, with good reason, does not permit large groups to gather.

But this night for two hours the men were allowed to live as normal people. The guards knew there was no problem; their presence did not break the atmosphere of peace, hope and

friendship. It was easy to love that moment, witnessing a cold, concrete place filled with warmth and light. The prison disappeared.

What had gone on before that in our years at Rikers was simply an apprenticeship. The Holy

Spirit was just winking.

We were on a road and could not go back, determined to find a functional place of rendezvous for both prisoners on release and their families.

Abraham House and its programs would be the outcome.

Friends in the Department of Correction brought a reservoir of wisdom to our search.

. . . it was they who set in place the first stones to build this house and grounded our plans in reality.

We knocked on doors, pursued leads, visited foundations, vacant rectories and politicians, and were repulsed more places than I can recall.

I even called, without an appointment, on Cardinal O’Connor. His housekeeper was reluctant to let me in, but the Cardinal listened to my dream.

"No one has talked to me before about this," he said. "Let me study this."

In prison you develop an infinite capacity to be disappointed . . . You need armor to fight off the negativity and cynicism. . . .

But by February 1997 Cardinal O’Connor was visiting a functioning Abraham House, and that experience was for him an awakening that made him passionate in calling for the establishment of more Abraham Houses.

We encourage others concerned with criminal justice to make that initiative in their own communities, and indeed, dozens of people come to study our program with this in mind.

But even as we plan to expand our facility, we intend to hold fast to being a family place. Our staff is convinced that only in this way can we change people and be a place of hope. Only this way can we be effective. Our roots are here in Mott Haven.

The way I see it, the Lord is the architect of Abraham House and we are handymen.

[Fr. Raphael]

"IF I DIE, COULD YOU SAY TO MY SON HOW IMPORTANT HE IS IN MY LIFE?

I WAS NEVER ABLE TO TELL HIM THAT.

PLEASE , COULD YOU TELL HIM?"

The chaplains at Rikers Island frequently are asked to find relatives and deliver messages such as the one that forms the title of this article. This message was from a prisoner who died of cancer soon after.

Sr. Amy Henry of Abraham House goes to extraordinary lengths to

fulfill these requests.

She catches a 5:15 bus most mornings for her 90-minute commute to the Rikers prison, rarely

returning before dark.

And she uses any free time crisscrossing the city to search out or care for inmates' families.

"They move, are illiterate, have no phones and lose touch," she says

. . . . Re-establishing family contact, no matter how tenuous, nearly always improves the inmates’ short- and long-term situation.

In New York . . . budget cutbacks are causing noticeable changes. Sr. Amy explains,

"I have men who are dying . . . their families fight for them . . . You must make a lot of noise to break through the inaction and rudeness. . . ."

"I know one mother who is a tiger and I say, ‘Good.’ She is getting what her son needs."

"Reduction in the number of guards makes ministry of even the simplest sort difficult. For a chaplain to visit every tier and each dorm weekly takes persistence . . . we never needed before.

"It does not matter whether the inmates are Muslims or Christians or have no faith at all. They may ask for a card to send to a dying sister or to a child.

"Sometimes they want me to make a phone call for them. They ask very little."

With that, Sr. Amy is out the door . . . .

Each month for 22 years she has visited the wife of a prisoner. The woman was shot in the spine and is a paraplegic in a Roosevelt Island hospital. The man himself died of a heart attack several years ago . . . .

Sr. Amy Henry

comes from France

and is a Little Sister

of the Gospel,

a small European

order of just 70 nuns.

Others include

Sr. Simone and

Sr. Rita Claus, the

Abraham House

nurse and supervisor

of our Food Pantry.

Abraham House

images ©

The Raphael book has no images illustrating the text. For design and informational purposes, relevant images have been added and captioned by the webmaster.

|

I think of my bishop every day, when I pray for him at Mass. For, without ignoring the person in charge of the Department of Correction, it is the bishop who is my superior, who can call me on the carpet and ask me to report in detail. I think of him when I go to Rikers, when I see and try to understand, when I listen and try to respond. Or, more simply, I see and hear with him. It is an urgent need among all the others -- and without doubting the many forms of the church's care that are expressed within an archdiocese, I need to keep my home base, to retain the character of an envoy. Those are the channels in which the vital fluid runs and through which it touches so many of the wounded in this place.

So it is with my bishop that I look at the numbers and the realities that impose themselves here. For

example, 105,000 men and women entered Rikers in 1987. Some of them are still here. For most, these will be the most active and daring years of their lives, the years most fraught with consequences. They will spend those years in this abandoned society, in a ferocious and directionless violence, a majority of them black, drawn from all types of minorities, all of them poor. On occasion one sees the profound wounds of racism in the midst

of so many other hemorrhaging sores. What group, what "parish" outside prison has such a potential for explosion, such a thirst for answers, such a groping toward an impossible light, such need for the attentive, living, loving eyes of our church turned toward its needs?

. . . . there is a convent of cloistered nuns in Europe who pray every Monday with those who are praying at Rikers. They receive The Link, a newsletter from our Christian community, with items in English and Spanish.They write to us regularly, and they in turn receive letters from Rikers.

Certainly a solidarity in prayer and friendship exists, and it is a comfort to us. We solicit these prayers everywhere: monasteries, retreat houses, families, friends, groups of young people and those not so young, those we know about and, most often, those who remain discreet and unknown. For example, a group of Belgians of all ages, who include among themselves blind and handicapped people, took the trouble to make their solidarity with us the theme of their Christmas preparation. There is also

a woman, a volunteer prison visitor, who told me that before entering the prison walls she often had to pray a lot: "I couldn't

come here otherwise," she added. Or I think of another woman who was asked: "But doesn't it bother you, going into prisons? Aren't you afraid in there?" She answered: "No, not at all. I am not afraid of anything but sin" . . . .

In cooperation with the Office of Criminal Justice Ministries of the archdiocese and the Sisters of the Gospel, we very often make the plunge into another world, a world that is "outside" but so frequently is horribly marked by what goes on "inside" the walls of a prison. I am speaking now of the families, those who are affected first of all by what is happening

far away from them. They are so distant in their powerlessness, so close in their desire: the grandmothers who have to take care of the babies, the spouses or common-law wives who cannot manage in material terms, the children who play at calling each other daddy or who call the telephone daddy because that is all they see or know of their father. .

"Here, upstate," a prisoner who has been there for six years said to me, "we can't talk to each other about anything but prison stuff, things we can all see. It's impossible to talk about outside, about what is going on in our families. Who cares? Nobody would listen."

Another man has been there 15 years. We have known each other for eight. He has maintained a lot of energy, but his life is no longer the same. His wife couldn't bear his absence; she has a boyfriend now. He has a wonderful son, partly brought up by his grandmother. This friend of mine says that he feels well in the prison, even to the point that he no longer looks forward to getting out. His philosophy now is to abstract himself from everything and practice emptiness, like a Buddhist.

"If you want to, you can learn a lot in this prison; there are some good programs here. But it is also a very efficient school for crime."

"My wife came for the weekend for a 'trailer visit.' During that time my 28-year-old son, who is a drug addict and lives in New York, took the opportunity to sell everything he could find in the house. I feel now like a piece of shit!"

"I have gone through a lot in prison these last seven years. But I would like to get out for the sake of my four children. That is what I find hardest to bear here. They need me so much!"

"

In three years in prison, he had never been called for a visit, had never seen the waiting room. When the CO did call him, he didn't believe it. After the visit, he told us: "Now I will have something to think about. Today is an event for me!"

"They are always talking about building prisons. But what you see here, what you learn, is that there are people who don't belong in prison. Why not start by letting them out? Then there would be room for the others."

"There are some people here in prison who can't say anything about it. Sometimes they are innocent. But if they talk, if they say aloud what they know, somebody will settle accounts with their families. They'll be condemned to death."

The group upstate, and the families, as I have already said, are an extension and enlargement of our parish at Rikers. This is not official, and no effort is made to interfere with what goes on elsewhere. We have no special privileges. It is simply done in the name of friendship, and of what we once began together. The Sisters of the Gospel, especially Amy and Carmen, have taken this to heart as their first priority. If it were not such a matter of time and of means, we would all like to go there together. We do have, as I have mentioned, The Link, a quarterly newsletter that marks the unity of all of us and is our obligatory and practical response to the abundance of letters we receive. . . .

We need people like Jacques Travers, a magnificent brother in our neighborhood, the saint of Brooklyn, who was taken away much too early by cancer. He often came to Rikers: a giant, open-hearted man, extreme in his actions and in his work for the faith. He said one day: "Yes, I have eliminated authoritarianism, violence and lying from my conduct absolutely, because that style is neither Christian, nor human, nor effective." With his friends and ours from our beloved Catholic Worker, with Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, he wanted "a world where it will be easier to be good."

"If every family that had the means to do so would take in one homeless person, there wouldn't be a problem in New York," he often said.

Those who are suffering from AIDS, at Rikers or elsewhere, deserve a special mention. In 1988, forty-six died of AIDS in here. AIDS victims are first in the thoughts of many people. Their unique situation makes a powerful impact from top to bottom: those who fight, who hold on to hope or who have none left, those who plunge into the incomprehensible, and those who know nothing. Many are the memories of our meetings, of dialogues without masks, of approach, refusal, acceptance. Many are the memories of friendship. "I don't need nurses -- just the other sick people. We help each other." I think of Nicholas and some others who wanted so much not to die in prison. I think of this one, departing in freedom, another in ridicule. "Why do they let somebody die in prison?" To that question I have no answer. . .

This prison at Rikers is not my kingdom. But I agree with what an Andean bishop said: "A people and the gospel are enough for me." At Rikers, as I hope I have shown, there is a people, and there is the gospel. So I can say, without being deaf

to the cries or blind to the responsibilities, "That is enough for me.

We need to talk to one another. If my readers retain nothing from these pages except that one simple but pressing invitation, it will be enough; for talking, in prison or anywhere else, is often life itself. It means killing the beast. It means keeping, in this place where its rejection is so natural, the proof of human existence. A world built solely on justice, on law, cannot replace a world of dialogue.

How many times have I witnessed the frustration of prisoners who have never had the chance to explain, to tell from start to finish what has happened to them. How many know nothing of their lawyers, have never seen them, have no idea what is going on. And when they are Hispanics or others who do not understand the language, the darkness is multiplied.

I am not absolving anyone or justifying anything, but how often have I seen the hate and tension melting simply because of a word, a dialogue begun even through the bars. In this house full of thunder and lightning, conversation is often the pearl that redeems everything; it means recognizing that it is only our sorrow that makes us human. It means not just "seeing" the other person, but learning about him or her and discovering something new together. It means assisting the other's self-discovery, because when we try to hide from everything, we no longer know who we are. And there are a lot of escapes here.

People hate what they do not know, says the Arab proverb. We have to break the glass of separation and ignorance. There is nothing else that immediately reveals our good conscience. Even if it is far from being a solution to everything -- even if it is just a good beginning -- we need to learn to talk to each other, especially when we think that everything separates us. In prison, you die of emptiness and being forgotten. . . .