|

Below: three sites that connect in history -- all within walking tour distance of each other.

|

|

|

Above: Jefferson Market jail. Behind it the court & tower.

|

|

|

Above: Washington Square Park arch

by Sanford White.

|

|

|

Above: The Triangle Factory Building a national landmark.

|

History can be told in different ways. One is to retrace interesting connections that emerge from it. For example: fire seems to recur as an element in the story of the women’s jail in Greenwich Village.

The beautiful bell and clock tower that serves as an elegant architectural explanation point for the landmark former Jefferson Market Courthouse, now a branch library, has as its antecedent a fire tower.

In 1832, the city fathers granted the villagers’ petition to erect a market at 6th and Greenwich Aves. But the growth in the area’s activity, while desired, prompted fire safety concerns. So a wooden tower for fire lookout was erected. The watchman, perched 100 feet above ground, would ring the bell to call out volunteer firemen. The number of rings signaled the fire’s location.

The wooden sentinel itself eventually burned down. Its replacement, the current tower, was built in 1875, part of a courthouse, jail, and market complex completed in 1877. The High Victorian Gothic styled courthouse with its attached tower was voted one of the 10 most beautiful buildings in the U.S. by a national poll of architects in 1885.

Whether top architect Sanford White, designer of the Washington Square Arch within walking distance of the courthouse, voted for it is not recorded. Known is that the man who killed White was tried there in 1906. Back then newspapers tagged it the Girl in the Red Velvet Swing case. Today, the library’s patrons are more likely to recognize the notorious case from the film and stage musical loosely based on it in E. L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime.

In 1909, garment workers picketed the Asch Building on Washington Place about a block east of White’s arch. They were protesting sweatshop conditions at the Triangle Shirtwaist Co. Dozens were arrested and hauled off to nearby Jefferson Market Court cells. Their being tried in Women’s Night Court, usually the preserve of prostitution cases, was viewed by supporters as intimidation and smear tactics. Two years later, 146 workers -- most young women -- died in the infamous factory fire, killed by flames, smoke, stampede, falls or jumps from windows. A Factory Investigating Commission was set up to probe, not only Triangle sweatshop conditions, but also other factories.

|

|

Frances Perkins.

|

With state legislators Robert F. Wagner Sr. and Al Smith as chairman and vice chairman respectively, the panel tapped Frances Perkins as investigations director. A worker safety expert whose social activism grew from settlement house involvements, Perkins would become President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s labor secretary, the first female cabinet officer. Her husband was a close aide to fusion reform Mayor John Purroy Mitchel who appointed the first woman ever to run a major NYC municipal agency, Correction Commissioner Katharine Bement Davis who made upgrading Women’s Night Court/Jail a top priority.

Perkins’ staff of investigators included Ruth E. Collins, 23, recently arrived from Grinnell College, Iowa. The commission’s investigations and recommendations resulted in NYS’ industrial code being rewritten and 36 laws being enacted to protect workers on the job.

The Jefferson Market and jail were demolished in 1927 to make way for construction of the Women’s House of Detention. On March 29, 1932, invited guests toured the just completed facility and met its first superintendent.

|

WPA artist Lucienne Bloch

working on Women’s House of Detention mural.

|

Her name: Ruth E. Collins, who after the Factory Investigating Commission had become a district superintendent with Kansas City's Provident Association, a social welfare agency that operated various institutions, programs and services for the needy including those made homeless and destitute by fire or other calamity.

A statement by Superintendent Collins was quoted at length in a keepers union magazine article about the opening of the new female inmate facility.

The publication On Guard lead article in the April 1932 issue read, in part:

“The new $2,000,000 House of Detention at 10 Greenwich Ave. was thrown open for inspection the afternoon of March 29 . . .

“Miss Ruth Collins, the superintendent of the House of Detention, who was appointed . . . because of her special fitness for the position, when asked about her new duties, spoke enthusiastically of the work." She said:

“A score of years ago, an appropriation was made for a Municipal House of Detention for Women. Since then, from time to time, plans have been drawn up, only to be discarded, and it remained for the present administration to make plans that proved a reality.

“In place of the wretched and desolate quarters of the old Jefferson Market Prison, at one time hailed as a remarkable step in advance, replacing the inhumane and dungeon-like city prison of early days, there stands a modern structure providing hygienic and wholesome environment, with most ample possibilities for segregation of types of offenders; splendid facilities for organized recreation, wholesome work rooms and medical equipment adapted to every need.

|

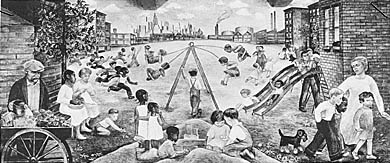

Detail from mural in the Women's House of Detention.

|

“In the old prison, the custodial staff was merely to guard the body. In our new project, the architectural structure is only half the story. Our entire personnel is motivated by an interest in the offender's well-being. We can truly say we are approaching a new era in penology.

“A major portion of the women who will be confined . . . represents social problems. It is our task to help them in readjusting to society's demands. Aside from their distressing need of physical rehabilitation, we hope to contribute towards their moral and social rehabilitation, proving that a prison can be a place for restoration as well as for punishment. To accomplish this, they cannot be served as a class; each one presents a different and distinct personality. To treat them individually, studying the influences in their background and doing all that we can to counteract those influences, is the program which this new institution has made possible.

“It now remains a challenge to all of us who are on the staff to accomplish the ideals of Commissioner Richard C. Patterson and his associates, the advance step they took when they inaugurated plans for this splendid institution.”

|

Detail from mural in the Women's House of Detention.

|

A matron writing about Collins in a later issue of On Guard speaks of the superintendent as having a cheerful disposition, striving “to make things bright,” giving encouragement and support to the staff. WPA muralist Lucienne Bloch, daughter of composer Ernest Bloch, wrote in the 1930s about the same “make-things-bright” trait in Collins (whom records indicate continued as the jail’s superintendent at least into the late 1940s, and possibly into the early 1950s):

“At my first visit to the Women's House of Detention where I was assigned to paint a mural, I was made sadly aware of the monotonous regularity of the clinic tiles and vertical bars . . . . it seemed essential to bring art to the inmates by relating it closely to their own lives . . . I chose the only subject which would not be foreign to them—children—framed in a New York landscape of the most ordinary kind. . . . The tenements, the trees, the common dandelions were theirs.

|

Lucienne Bloch’s "Cycle of a Woman's Life from Childhood to Womanhood" mural in the Women’s House of Detention .

|

“The superintendent of the House of Detention . . . did not, at the time, feel that New York and ragged children were suitable subjects to be painted in permanent form on the prison walls. She then believed that "nature scenes" of a fantastic kind "would be more inspiring" and would not remind the inmates of unpleasant associations.

“Only when I had fully developed my sketches and had made the gas tanks glitter in the distant blue, had drawn out each pert braid . . . did she appreciate that my approach to the subject was intended to relate . . . to the intimacy of the lives of the inmates. Craftsmanship won her over. As the work progressed, her interest grew, and she often stood by the scaffold and eagerly discussed my problems with me.”

The mural presumably was demolished with the jail in 1974. Collins died a year earlier at age 82.