xxx

xxx

NYCHS presents excerpts from From Newgate to Dannemora: The Rise of

the Penitentiary in New York, 1796-1848, by W. David Lewis.

Copyright © 1965 by Cornell University; copyright renewed 1993.

Used by permission of the author and the publisher, Cornell

University Press. All rights reserved. Click on image, based on book jacket front cover, to access Cornell University Press site.

|

|

Chapter II: The First Experiment

(Part III)

(Excerpted from Pages 43 - 53)

. . . . There was a brief surge of economic prosperity during the

embargo period and the War of 1812 probably because

of the increased demand for domestic manufactures during the

years of nonimportation and conflict.

Production at Newgate

leaped considerably; by 1815, the prison was turning out brushes,

spinning wheels, clothespins, bobbins, spools, butter churns, washtubs, pails, hoops, wheelbarrows, machinery, cabinets, whips, and

a variety of woven goods.

At least seventy looms were in operation,

and the agent was considering the introduction of steam power.

Markets were sought not only in the New York City area but also

in New Haven, Hartford, Providence, and Newport.

An anonymous staff member who wrote a description of Newgate in this

period was optimistic about its future. He conceded that the

institution was not perfect, but believed that each passing year

would “add to its improvement.”

In 1813, prison administrators

hailed a temporary slackening in the pace of congestion as “a

decisive proof of the efficacy of the system, and highly consolatory

to the patriot and philanthropist.”

These promising conditions did not last. A crime wave, related

at least in part to difficulties facing returning soldiers seeking

employment, occurred after the War of 1812, and there was a great

increase in the number of offenders sentenced to Newgate.

xxx

The fourth man to serve as NYC mayor during Newgate's operation was Marinus Willett (1807-08). The new National Park Service Collections Management and Education Center (above) that opened in July 2005 at Fort Stanwix National Monument in Rome, N.Y., is named for him in honor of his heroics against British and Indian forces as second in command at the fort during the Revolution.

After the war, Willett (left) moved to NYC, where he was elected to the Assembly in 1784 and year later appointed sheriff, a position he held until 1788. After service as President Washington's peace commissioner to the Creek Indians, Willett was reappointed in 1792 for another four-year term as sheriff After the war, Willett (left) moved to NYC, where he was elected to the Assembly in 1784 and year later appointed sheriff, a position he held until 1788. After service as President Washington's peace commissioner to the Creek Indians, Willett was reappointed in 1792 for another four-year term as sheriff

In 1807, he was chosen to succeed DeWitt Clinton as mayor of New York City. But after a couple of years, Clinton regained that office and later defeated Willett in a race for lieutenant governor.

Below is an image of the Willet memorial rock at Albany's Washington Park bearing a plaque that reads: In grateful memory of Colonel Marinus Willett (1740 - 1830). For his gallant and patriotic services in defense of Albany and the people of the Mohawk Valley against Tory and Indian foes during the years of the War for Independence, this stone brought from the scenes of the conflict and typical of his rugged character has been placed here under the auspices of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York by the Philip Livingston Chapter of Albany. A. D. 1907

xxx

(Click images in this box for their respective web site sources.)

|

|

The pardoning power could not be used frequently enough to keep

the prison population in bounds, despite a wholesale use of the

prerogative in 1816. . . .

Convicts were "literally crammed into their rooms

at night," and could scarcely move in the crowded apartments.

Authorities feared that a sudden epidemic of sickness might decimate the ranks of the inmates, and wondered whether or not a

return to the sanguinary system of the days before 1796 would

occur if conditions were not rectified.

The unsettled commercial

conditions after the war hurt the institution financially . . . . By 1816, the prison was deeply in debt and

burdened with heavy inventories of unsold merchandise.

Under the pressure of these conditions the legislature embarked

upon a series of efforts to remove some of the defects in the penal

system. In 1816, it authorized the construction at Auburn of a new

prison which was destined to become one of the most famous

institutions of its kind in the world.

In 1817, . . .

the lawmakers required convicts to work only on raw materials

brought to the penitentiaries by private entrepreneurs who agreed

to pay a fixed labor charge to have them made into manufactured

goods.

If the prison population exceeded 450, the governor was

authorized to permit the employment of any number of inmates in

such ways as he deemed proper. Permission was granted to allow

felons to be used in canal construction, provided the entrepreneurs who contracted for them were willing to bear the burden

of their expense and upkeep while on the job.

Inventories of prison-made goods which had accumulated over the years were to

be sold at auction for whatever they would bring.

At the same time, the legislators attempted to mitigate overcrowding and bring some order into the pardoning situation.

Out of 419 men sentenced to Newgate for grand larceny, half had stolen

less than $25 each; any theft of this amount or less was therefore

redefined as petty larceny, punishable by fine or imprisonment in

a county jail instead of consignment to the state penitentiary.

The

chaotic pardoning system was altered by allowing the prison

inspectors to abridge an inmate’s term by one-quarter for good

behavior and a satisfactory production record.

As a further incentive to diligence, it was provided that 20 per cent of all convict

earnings over and above the cost of support were to be set aside

for the prisoner or his family upon release. . . .

xxx

xxx

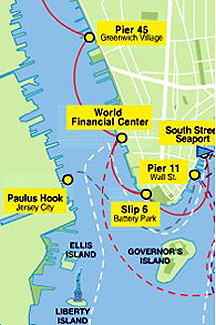

Jacob Radcliff (below right) was the fifth man to serve as NYC mayor during Newgate's operation. He is credited with helping found Jersey City as a partner in a real estate venture at Paulus Hook ( 1823 sketch above)

A NY Assemblyman in 1794-95, an assistant NY attorney general 1796-98, and NYS Supreme Court Justice 1798-1804, he co-authored NYS laws codification in 1802 and served as NYC mayor 1810-11 and again 1815-18. He was known for having granted many certificates of freedom to Negroes. He was a leading Federalist of his time. A NY Assemblyman in 1794-95, an assistant NY attorney general 1796-98, and NYS Supreme Court Justice 1798-1804, he co-authored NYS laws codification in 1802 and served as NYC mayor 1810-11 and again 1815-18. He was known for having granted many certificates of freedom to Negroes. He was a leading Federalist of his time.

Radcliff (also spelled Radcliffe) appears to have the distinction of being first at least -- and perhaps the only -- former academic librarian to serve as NYC mayor. He was for a while librarian at the Dutchess County Academy.

Paulus Hook (1780 map detail left) was a piece of land lying east of what is now Jersey City's Warren street, and included some sand hills. On the north was Harsimus Cove, First street; on the east the river, on the south Communipaw Cove, South street, and to the west, salt marsh, covered by water at high tide. Paulus Hook (1780 map detail left) was a piece of land lying east of what is now Jersey City's Warren street, and included some sand hills. On the north was Harsimus Cove, First street; on the east the river, on the south Communipaw Cove, South street, and to the west, salt marsh, covered by water at high tide.

The site was sold by the West Indian Company to Abraham Isaacsen Planck in 1638 and remained in the Planck family until 1699, when it was sold to Cornelius Van Vorst. The land had been used mostly for farming but in the very early 1800s Anthony Dey, a lawyer, purchased Paulus Hook with ferry privileges from Van Vorst's descendant. The site was sold by the West Indian Company to Abraham Isaacsen Planck in 1638 and remained in the Planck family until 1699, when it was sold to Cornelius Van Vorst. The land had been used mostly for farming but in the very early 1800s Anthony Dey, a lawyer, purchased Paulus Hook with ferry privileges from Van Vorst's descendant.

The property was surveyed, streets mapped, before title transferred to Dey, Col. Richard Varick, former NYC mayor, and Dey's cousin; Radcliff, later NYC mayor. Alexander Hamilton initially acted as their attorney and drew up the incorporation charter.

Paulus Hook remains part of NY-NJ continuing ferry history as a NY Water Taxi service stop (route map above).

(Click images in this box for their respective web site sources.)

|

|

Throughout Newgate’s history the usual punishment for infractions of prison rules had been solitary confinement on shortened rations, and the use of corporal inflictions had been

prohibited. . . .

In 1816, the agent

and the inspectors complained that the threat of ordinary punishments was insufficient to deter convicts from plotting arson. The

following year, the legislature prescribed the death penalty for any

inmate who committed arson or assaulted an officer with intent to

kill, but even this failed to improve the situation.

In June, 1818,

unrest among the prisoners culminated in a severe riot. According

to the inspectors, “a large majority of the convicts were concerned,

and the institution was literally threatened with total destruction.”

Military force had to be summoned before the violence subsided,

and even after about one hundred ringleaders had been placed in

solitary or restricted confinement their conduct became so outrageous that the sentinels patrolling the walls were told to fire

among them.

The legislature responded to such troubles with an act in April,

1819, legalizing flogging at both Auburn and Newgate. No more

than thirty-nine blows were to be inflicted upon one occasion, and

then only by the principal keepers under the direction and supervision of two inspectors. The use of stocks and irons was also

permitted.

This was a highly significant enactment. It in effect constituted

an admission by the lawmakers that the penitentiary system was

now deemed unworkable unless certain relics of the sanguinary era

were superimposed upon it.

Paradoxically, the new law actually

made it possible for criminals to be punished more inhumanely

than would have been the case under the old penal code.

Whereas

a thief might have been given thirty-nine lashes under the old

system and then set free, he could now be sentenced to a long

prison term and flogged repeatedly if he did not conform to certain

rules under confinement.

Although the act of 1819 was clearly

worded to guard the exercise of the chastising power from abuse,

its provisions were not always scrupulously obeyed, and in time

practices came into being which might have astonished the legislators who enacted it. For better or worse, the New York prison

system had acquired one of its most controversial features.

The lawmakers . . . attempted to cope with some of the disciplinary problems

facing the prisons by inaugurating a system of classification. Penal

administrators were required “to separate and keep alone and

apart from the other convicts, those prisoners who have been convicted of the higher crimes, those who have been twice, or oftener,

imprisoned, those who are young, those who are old, those who are

healthy, and those who are unhealthy.”

xxx

xxx

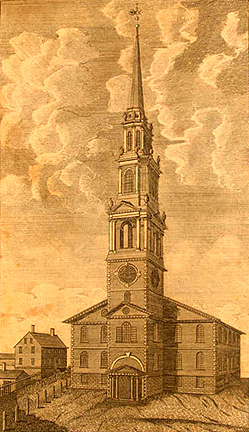

The first chaplain at Newgate penitentiary, the Rev. John Stanford, had been ordained in England in 1781 at age 27, came to the U,S. five years later and

first worked as a pastor in Virginia but and later at the 1st Baptist Church of Providence, Rhode Island, arriving there about after its third meeting house (above) was built.

That church traces its origins to the congregation begun by Roger Williams, thus identifies itself as the 1st Baptist Church in America, and still meets in the same basic structure (below left) as when the Rev. Stanford served there.

His attempt at writing the congregation's early history has been cited in later and more detailed chronicles such as Thomas Armitage's monumental The American Baptists. His attempt at writing the congregation's early history has been cited in later and more detailed chronicles such as Thomas Armitage's monumental The American Baptists.

In 1789, Rev. Stanford helped build the Fair (later Fulton) St. Baptist church in Manhattan, serving as its pastor until 1801 when fire destroyed it.

He was an itinerant preacher in the East for about a decade before his 1812 appointment as chaplain to Newgate. He became a leading advocate for separating children from hardened criminals, especially to provide for the proper education of the young. He also helped establish New York House of Refuge, the first juvenile reformatory in the U.S. The Rev. John Stanford died in NYC on Jan. 14, 1834 age 80.

Author W. David Lewis, in this book's concluding chapter An Essay on Sources, notes the New-York Historical Society possesses a small group of papers by Rev. Stanford, mostly drafts of government published reports.

(Click images in this box for the images' respective web site sources.)

|

|

Although this provision

was significant in that it anticipated later correctional developments, it was difficult to impose upon institutions which had not

been designed for such a degree of separation.

Officials at Newgate

implemented it to some extent by placing various types of offenders in different sleeping rooms at night, but it was still possible for

divergent groups to mingle in the daytime.

John Stanford went

beyond this by advocating the establishment of an "honor group"

of inmates who had good behavior records and likely prospects of

rehabilitation, but this was not carried out . . . .

Other events calculated to ease pressures at

Newgate occurred in 1824, when a House of Refuge was provided

for juvenile delinquents, and in 1825, when a law was passed

permitting insane convicts to be transferred to the Bloomingdale

asylum in New York City. . . .

Although the contract system decreed by the

act of 1817 was not completely strange, having been briefly used

at Newgate some years before in the manufacture of shoes and

nails, the prison did not satisfactorily adjust to the new legislation.

In 1818, its profits sagged to $16,000, not nearly sufficient to defray

costs of $58,000 for food and maintenance alone. The inspectors

complained that it was difficult to make contracts, and urged a

temporary return to state accounts.

The auction sale of goods

which had piled up in storage did not help very much, for these

wares had deteriorated into a condition of virtual unsalability.

The prison economy had barely begun to recover from the effects

of the contract law when it was staggered by the Panic of 1819.

The failure of the shoemaking contractor threw many inmates out

of work for over three months until a new agreement was signed

specifying rates 40 per cent lower than those prevailing before.

Prisoners engaged in sawing marble were also idle for a time.

The fact that such conditions were bad for disciplinary as well as

financial reasons probably explains various evasions of the law of

1817. By 1821, less than half of Newgate’s industries were running

on a contract basis, legislative pronouncements notwithstanding.

Economic conditions gradually improved at the prison, and in

1821 the agent indicated that the worst was over. All able-bodied

convicts were employed, and labor was securing a better return.

By dint of rigid economy a better balance was achieved between

intake and outgo, and in 1826 the institution’s financial progress

elicited praise from Governor DeWitt Clinton.

Nevertheless, the

goal of self-support remained elusive, and enemies of the prison

derived satisfaction from pointing to the large sums which the

state had expended for its upkeep over the years since its founding.Whatever economic headway the penitentiary made came too

late to save it from its critics, and was more than counterbalanced

by the chronically poor state of its discipline.

xxx

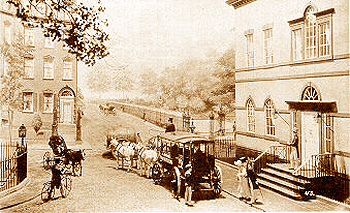

Above is an illustration of Government House at Bowling Green that figures in the story of John Ferguson, (below right) the 6th of the 10 men who served as NYC mayor during the three decades or so that Newgate, officially the

"New York State Prison of the City of New York," operated.

The chief value of his brief mayoralty -- less than a year -- is the perspective that it provides on the politics of the era. Mayor DeWitt Clinton's flirtation with Federalist causes and his lack of total support for Jefferson and Madison causes provided the opening for enemies within his party to prevail in their efforts to have him removed as a mayor in 1815.

In those days, NYC mayors were appointed by a Council of Appointments controlled by the governor. Tammany Hall threatened Governor Daniel D. Tompkins it would withdraw its support if Clinton were not removed and replaced by one of its own, Grand Sachem Ferguson, at least temporarily.

So Ferguson served as mayor for only a matter of months until he got the post he really sought -- that of Naval Officer of the Port of NY.

So Ferguson served as mayor for only a matter of months until he got the post he really sought -- that of Naval Officer of the Port of NY.

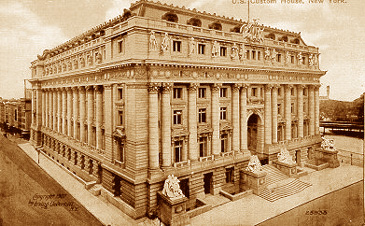

To appreciate his preference, consider that port cities' Custom Houses were major centers of federal revenue, political patronage and potential graft.

Before the federal income tax, the chief source of revenue was the duty charged on imported goods. The Port of New York Custom House was the federal government's largest agency office, with more jobs, more revenue, and more opportunity for power and personal gain than any other.

The position of Port Naval Officer, a powerful post in the operation of the Custom House, was a presidential appointment requiring U. S. Senate confirmation. There is no record reflecting negatively on Ferguson's discharge of his responsibilities as NYC Port Naval Officer -- a post he held by virtue of repeated presidential appointments and U. S. Senate confirmations -- until his death in 1832.

Nevertheless, it may be worth noting

- that in 1813 the City of NY acquired the elegant brick Court House building and its site at the Bowling Green tip of Manhattan Island, and

- that in 1815, the year Ferguson became the Port Naval Officer, the site was sold a developer who torn down the structure (actually known as Government House whose image appears at the top of this box) and replaced it with seven fine upscale row houses.

Eventually, the federal government acquired the land and built the landmark Custom House that presently occupies the site (image below).

xxx

(Click red-border images in this box for their web site source.)

(Click red-border images in this box for their web site source.)

|

|

Although continued overcrowding and an inability to prevent

plotting by separating inmates were circumstances which officials

could do little to alter, many of Newgate’s disciplinary shortcomings were traceable to ineffective administration.

The inspectors, for example, held wide discretionary powers under the

penal act of 1796 to regulate the admission of visitors but failed

to make good use of them. It became customary to permit anybody -- even a child -- to enter the prison grounds upon paying a

small fee: visitors became so accustomed to regarding their entrance as a right that they threatened lawsuits if excluded, and

penitentiary officials timidly bowed to such pressure.

Many visitors

brought the felons such items of contraband as rum, tools, money,

and unauthorized messages.

In addition, alcohol and other forbidden items were smuggled into the institution by contractors,

who used them as bribes to secure better work from inmates.

Supervision of convict life was generally lax. Indiscriminate

jostling’ and confusion was allowed to prevail in the yard; on Sun-

days in particular the felons milled about freely, sang obscene

songs, wrestled with one another, and carried on petty gambling.

An investigating commission from the state legislature reported in

1825 that the inmates were insolent, that idleness was widespread,

that one convict was actually sleeping at his work, and that another

had sabotaged his stock of materials without being punished for

it.

Sanitation was evidently poor, for one visitor stated in 1826

that Newgate’s prisoners were in a filthier condition than any he

had ever seen, with the exception of those confined in the notorious

city jail at Washington, D.C.

Possession of knives among convicts,

difficult to prevent at any prison, was widespread; such weapons

were used either to damage industrial goods or to gain revenge

upon informers.

In a vain attempt to induce better behavior the

inspectors placed large placards at various places bearing such

inscriptions as, "He that will not work shall not eat," "The way

of the transgressor is hard," and "He that walketh uprightly

walketh surely, but he that perverteth his ways shall be known," but as one hostile critic pointed out, these were poor substitutes for

effective discipline.

Under such circumstances the fact that

officials managed to avoid a repetition of the ugly riot of 1818

must be attributed as much to luck as to superior management.

xxx

xxx

A statue of Cadwallader David Colden, the 7th of the 10 men who served as NYC mayor during Newgate's 30+ years, gazes down from a ledge of the landmark Surrogate Courthouse at the usually busy Chambers & Centre Streets scene.

A Federalist, he was the grandson of colonial NY's Lt. Gov. Cadwallader Colden, one of pre-Revolutionary America's leading scientists. Colden lands were confiscated after Independence yet the grandson succeeded politically nonetheless, serving as District Attorney, Assemblyman, State Senator, and U.S. Representative (from Queens) and as NYC mayor (1818-1821).

A friend from youth of Robert Fulton, Colden's bio of the steamboat pioneer is one of the primary historical sources on the inventor's life. Grandfather Colden, who served as the first colonial representative to the Iroquois Confederacy, also wrote a book that has become a primary historical source, The History of the Five Indian Nations.

Ex-mayor Colden, after a long NY political career, moved to Paulus Hook (Jersey City) and became president of Morris Canal & Banking Company. Port Colden, along the canal route, was named for him. Its historic district (image below) in Washington Township, Warren County, N.J. is a favorite of canal buffs.

xxx

(Click images in this box for their respective web site sources.)

|

|

In

1823, when news arrived that a prison had been burned in

Virginia, a portending insurrection at Newgate was quashed only

with the aid of informers and other loyal inmates. . . .

Thomas Eddy himself condemned the design of the institution

he had built . . . He confessed to Peter Jay in

1816 that "a most striking error" had been committed in his plan,

which should have provided for five hundred solitary sleeping

rooms.

In 1818 he made the same admission in a memorandum to

DeWitt Clinton. "No benefit, as it regards reformation, ever has

been, nor ever will be produced," he told an English penal reformer a year later, "unless our prisons are calculated to have

separate rooms . . . so that every man can be lodged by himself.”

Such men as Eddy advocated abandoning the old prison altogether and

building another where new techniques could be used in facilities

designed expressly for the purpose, an idea that seemed especially

cogent after the development at Auburn of an ingenious system

featuring solitary confinement at night and group labor in silence

by day.

One attractive possibility was the construction of a new penitentiary near large marble deposits at Sing Sing in Westchester County which could be quarried by inmates. After considerable agitation and deliberation this idea prevailed. On March 7, 1825, the legislature authorized the building

of a new prison, which commissioners shortly thereafter placed at

Sing Sing "on account of its marble-beds, its accessibility by water

and its salubrity.'

The Common Council of New York City purchased Newgate for use as a debtor’s prison and bridewell, and when the new penitentiary was completed in 1828 the state

abandoned the old institution altogether. Officials at Newgate

fought against this series of events, arguing the superior rehabilitative value of diversified penal industries as opposed to

marble quarrying and criticizing the harsh treatment of the convicts who were building the prison at Sing Sing, but it was of no

use. New York’s first experiment in penitentiary management

had come to an end. . . [but] prison administrators in

the Empire State eventually devised a system which, for all its

borrowings from outside sources, possessed a high degTee of

originality.

|

Table of Contents

|

- [Book jacket blurb, images]

- Preface

- The Heritage

- The First Experiment

- The Setting for a New Order

- The Auburn System and Its Champions

- Portrait of an Institution

- The House of Fear

- The Ordeal of the Unredeemables

- Prisons, Profits, and Protests

- A New Outlook

- Radicalism and Reaction

- Ebb Tide

- Change and Continuity

- A Critical Essay on Sources

|

|

The keynote of the new approach was isolation. John Howard

had advocated separating convicts at night . . .

American prison leaders now turned to these ideas, reasoning that

the way to correct the evils arising in a society limited to criminals

was to prevent any meaningful society from being formed in the

first place.

At such new penitentiaries as those at Auburn and

Sing Sing, the convict was to be so completely cut off from his

fellows as to be incapable of corrupting them or of being the

recipient of evil influences.

At the same time, he was to be subjected to such constant surveillance and coercion that he would

have no choice but to conform to the rules established by those

who had control over him.

Such treatment would surely punish; would it also reform?

Would it stimulate the mind to reflect upon better things and

induce repentance, or would it stupefy the prisoner’s intellect and

make him even less fit for normal social life? Would it work in

practice?

These were some of the questions that confronted penal

reformers in New York as the search for an effective penitentiary

system shifted from old and discredited Newgate to grim new

institutions which rose on the banks of the Owasco Inlet in

Cayuga County and the Hudson River at Sing Sing.

NOTE: None the above images of, or related to Mayors Willet, Radcliff, Ferguson and Colden and the Rev. Stanford

appear in Lewis' book. Nor did the captions. Image sources can be accessed by clicking the red-border images, from

respectively the National Park Service at Fort Stanwix National Monument, the Educational Technology Clearinghouse

of University of South Florida, the Albany Times Union Newspaper article on Washington Park Conservancy website, GetNJ.Com, New Jersey City University "Jersey City:Past & Present project, NY Water Taxi, Library of Congress'

"Religion and the Founding of the American Republic," the 1st Baptist Church in American, U.S. Bankruptcy Court

Southern District of NY, Mark Lentz' photo gallery on PBase.Com and Washington Township Historic Preservation Commission in Warren County, N.J.

|