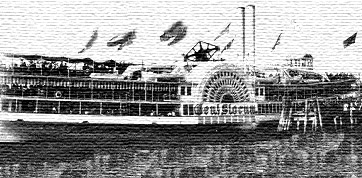

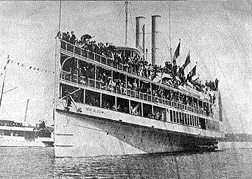

The story of the General Slocum has been retold many times. How on a bright June morning somewhere

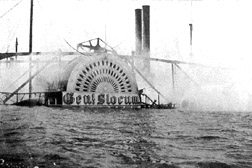

between 1,200 and 2,000 people, mainly mothers and children, boarded the General Slocum for a cruise to Long Island Sound, a picnic at Locust Grove, and a returning cruise with sunset and stars. Two hours after leaving the dock and sailing up the East River through Hell Gate, the ship was ablaze from bow to stern and passengers, many already being burned alive, were jumping overboard. Few would survive both the fire and the water, since in 1904 few New Yorkers knew how to swim.

First person interviews done within hours of the tragedy were included in the newspapers of the day. The Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York published his report, which listed the fatalities, the injured, and the missing as a book. Several authors have recompiled the data over the years describing in infinite detail the horror of the moment. For almost 100 years the story of the burning and sinking of the General Slocum excursion paddlewheeler stood as the greatest tragedy in the City of New York, and indeed, among the greatest disasters of history.

What began as a recreational cruise, a Sunday school outing for St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, became an event so cataclysmic that it devastated the largest ethnic German community in the United States, and acted as a

catalyst for sweeping changes in how the public and the law looked at marine commercial transportation.

Stories abound of the heroic fireboats and tugs, which raced to the scene, picking up victims along the way. Nearly all of the medical personnel on North Brother Island, where the flaming wreck came to rest, assisted however they could. Every inch of the island was used in the rescue, and then in the inevitable recovery of the dead. Virtually every facility on the river and both shores was pressed into service for the living and the dead. The Department of Public Charities sent doctors and nurses from Randall’s Island, Metropolitan, Infants’, and the Alms

House Hospitals.

But less well known are the stories of the people of Rikers Island. Before the disaster was over, bodies had arrived at Rikers Island, by boat and by current. They were held for transport to the temporary morgue

at 138th St. or the pier near Bellevue Hospital at 26th St. Some living victims were also delivered to the island and cared for there. One team of heroes in the best tradition of Aw, shucks, I didn’t do nuthin rose to the occasion at Rikers Island.

According to the New York Times, Dr. Nathan E. Broder (or Bruder) was on duty that morning supervising several prisoners of the workhouse. When the Slocum was sighted, fully ablaze, covered in smoke, and heading for North Brother Island, John Merther and Dan Casey, both prisoners literally compelled Dr. Broder to take them over to the scene of the rescue efforts.

[In fairness to Dr. Broder, one needs to remember that he risked being overcome by the two inmates if they decided to engage in an escape instead; so his initial reluctance is understandable from a security perspective.]

The three put out in a small rowboat, and worked as a team to

haul in bodies and living victims. They put in at North Brother Island to hand over their load, then returned to deep water for more. This was repeated until all were too tired to continue. They then returned to Rikers Island and their original assignment.

In another instance, the Evening Sun, that night, reported that the bodies of seven women and two children were picked up by a rowboat along with one woman and two small boys, who were still alive.

Was this the same boat manned by Dr. Broder and the prisoners? We may never know. I suspect it was another team of heroes who could not remain on the shore, safe while others perished.

Until now, June 15, 1904 and the epic of the General Slocum have been fodder for the writers of sensational fiction and refried press coverage. There has never been an effort to document the events of that day from the perspective of the families of the victims, heroes, caregivers, and bystanders. Their tales are no less dramatic, like the minister who so totally wore himself out caring for the families of the dead, that he also dropped dead after performing round the clock funerals.

Or that of my grandaunt who missed the boat to "play hooky" and spend the day with her fiancée. Her grandmother, two sisters-in-law, and three nieces died and three other relatives were injured.

The General Slocum Centennial Scrapbook contains the uniquely personal recollections of the survivors and their families, the good Samaritans, the heroes, the caregivers, the passers by whose families were touched by the largest maritime disaster and most deadly fire in New York City’s history. The stories were passed down, but never recorded until now. This project is dedicated to collecting the stories from the descendants, and where appropriate, linking the families. (Many of the passengers were inter-related by marriage or blood as well as their Lutheran faith.) In the case of my own family, there were Muths, Hessels, and Schnitzlers, aboard comprising a party of 15 grandparents, parents and children – all one family but from four separate households. In order to honor each family’s experience, each family’s story is related on its own page. Where several households within a larger family have contributed, each has its own page and their relationships have been documented. Each story is unique, just as each household was unique. By contributing their stories, these descendants have chosen to honor their families in a uniquely personal way. The General Slocum Centennial Scrapbook project will be actively seeking stories until publication in 2004. Those interested in giving or obtaining information, can visit the following web site for more information: |

||||||||||||||||||||