The Whitehall Connection

. . .The roots of New York State's Identification Bureau can be traced back to the once-bustling town of Whitehall, N.Y. . .Isaac V. Baker, a rail-road magnate and politician, was one of the town's most prosperous residents. Isaac Baker had two sons, Isaac V. Baker, Jr. and Charles K. Baker.

Isaac V. Baker, Jr.

Superintendent of NYS Dept.

of Prisons, 1882-1887.

|

Isaac, Jr. . . served alternately as an Assemblyman and a Senator until 1881, while also overseeing the interests of the rail-roads. The Baker family sold the State of New York a sizable portion of land outside of Comstock upon which the Great Meadow Prison was eventually built. Accordingly, Isaac V. Baker, Jr. was, in 1882, appointed Superintendent of the New York State Department of Prisons.

Charles K. Baker, also a North Granville Academy graduate and State Assemblyman, was given the position of Chief Clerk for the Prison Department, a job he held for nearly thirty years.

Another wealthy and well-landed family of the Whitehall vicinity were the Davis'. Emerson E. Davis, Sr. was an Assemblyman and a close personal friend of Governor Tilden. His daughter, Marion, became the wife of Charles K. Baker; his son, Emerson E. Davis, Jr. became a Prison Official.

Although not as wealthy or politically connected as the Bakers or the Davis', the Parke family of Whitehall also played a role in the early days of New York's Identification Bureau.

Capt. James H. Parke,

founder, American System of

Fingerprint Classification.

|

James H. H. Parke was a prominent local merchant who owed a large store and a great deal of property. His son, James H. Parke attended the North Granville Academy and was a good friend of Charles K. Baker. . .

While living in Whitehall, Parke joined the local militia and rose to the rank of Captain . . . speculating on investments cost him most of the family's wealth and holdings and, in 1898,. . .Parke turned to his friends in the Prison Department. On May 14 of that year, at the age of 50, he was granted a job as guard at Auburn Prison.

The Fingerprint Experiment

By the time Charles Baker returned from his second trip to Europe, Captain Parke had been transferred to the Prison Department's headquarters in Albany. Promoted to the position of bookkeeper, he was working as a parole statistician in Room 111 of the Capitol, the same room which housed the Bertillon Bureau.

The books Baker and Lamb had purchased in London were given to Parke along with the task of setting up a test fingerprint file for the Prison

Department . . .

Living with Parke was his 22 year old son, Edward . . .In time, the Parkes were able to decipher the intricacies of Henry's classification system. As it became clearer to them, so did its weaknesses.

The first and most obvious problem was storage. The Henry System called for fingerprints to be recorded on large paper sheets called 'slips.' These slips were filed flat on shelves or in pigeon holes, which consumed a great deal of space . . . This prompted Parke to propose developing a fingerprint form of stiff cardboard and of a less awkward size which could be filed upright in drawers as the Bertillon cards were. Superintendent Collins denied his suggestion . . .

The second problem with the English System was their method of dividing fingerprint records into primary groups. Henry's method of attaching values to each of the ten fingers and then accruing those values for any finger in which a whorl pattern appeared used first the even and then the odd numbered digits, which was unnecessarily complex.

What Parke proposed was to calculate the primary in a similar way, but using the patterns as they appeared in sequence on the fingerprint form--right hand first, then left hand.

A person with the fingerprint patterns Loop, Loop, Arch, Whorl, Loop in the right hand and Whorl, Loop, Whorl, Loop, Loop in the left hand would, under Parke's system, have a primary classification of 3 over 21, whereas the same person, under the Henry System, would have a primary of 15 over 1.

The only time a Henry Primary would match one of Parke's was when whorls appeared in all ten fingers (32/32), or in none (1/1).

Although Collins had denied Parke permission to convert to a more suitably sized fingerprint card out of concern for future exchanges with the British, he allowed this radical alteration of their filing system.

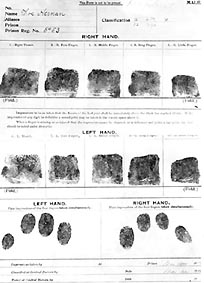

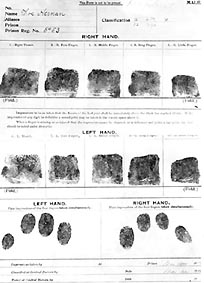

This fingerprint slip, dated

Mar/Apr 1903, is believed to be the

first set of fingerprints recorded by

James H. Parke for NYS Prison Dept.

|

Parke had slips made up measuring 8 1/2 by 13 1/2 inches which mimicked the English forms and in March of 1903, while accompanying the parole board on their rounds of the State's Prisons, began finger printing inmates . . .

The American System of Fingerprint Classification

. . . On Sunday, November 8, 1903, The New York Herald published a full page, illustrated article by Josiah Flynt entitled The Fingerprint of The Criminal. Mr. Flynt's article not only promoted the English System, but declared that no one in America knew anything about fingerprinting. . .

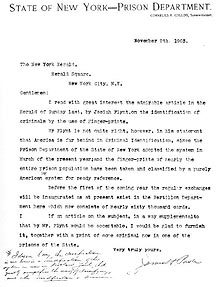

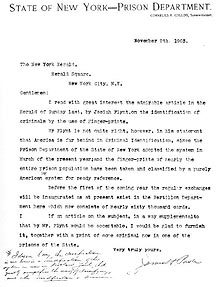

Parke responded the following morning with a letter to The Herald pointing out Mr. Flynt's oversight. In his rebuttal, Parke noted that he had taken the fingerprints of nearly the entire prison population of New York State and had classified them "by a purely American system."

Letter from James Parke

to The New York Herald,

November 9, 1903.

|

The next day Parke wrote to William Potter, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, providing him with a copy of Mr. Flynt's article and the proposition that he be allowed to visit Washington to demonstrate his system. . .

Despite increasing public awareness of fingerprints, Parke's only convert was Superintendent Collins, who began to place more credibility in Parke and his classification system. Early in 1904 all Bertillon Units in the State's prison system were ordered to begin collecting fingerprints along with Bertillon measurements.

By April of 1904, the details of Parke's system had been worked out. . .

In another show of support, Collins selected Captain Parke and Mr. Emerson E. Davis, Jr. (who was now head of Dannemora's Bertillon Unit) to represent the Prison Department at The Universal Exposition of 1904 in St. Louis, MO.

This was a grand opportunity for both Collins and Parke. It rekindled Collins' ambition of realizing a Central Bureau of Identification in Albany and boosted Parke's hopes of establishing his fingerprint formula as the North American equivalent of the Henry System.

|