|

|

between Auburn Theological Seminary & Auburn State Prison ©

Each Sunday morning a group of students accompanied by a professor walked the short distance from the seminary

to the prison. Enroute they had to make a transition between the warm, uplifting, supportive atmosphere of their

campus where religion was revered, to the cold, negative and rather grim atmosphere of the prison where religious

zeal and compassion were, at best, of secondary importance to staff and keepers.

Inside the walls absolute control of all facets of life for prisoners was of primary importance to officials. Staff members

understood that men were sent to prison to preserve society from their violence and their crimes. It was the duty of

the staff to hold the inmates as ordered by the courts.

In Page 8 of NYCHS' presentation of Why Auburn? elsewhere on this web site, John Miskell's text refers to a 1931 purchase by NYS of 67 South Street from the Allen Dulles estate, the property subsequently serving as the residence for Auburn wardens.

The name mentioned in that 1931 estate reference was, of course, not the Allen Dulles who would serve as Central Intelligence Agency director from 1953 to 1961. The latter (Allen Welsh Dulles) was the son of the Rev. Allen Macy Dulles, professor at Auburn Theological Seminary and minister at Watertown's 1st Presbyterian Church.

What became the home for Auburn wardens was purchased from the estate of Pastor Allen Dulles who died in 1930 at age 76. Each year Princeton University presents an Allen Macy Dulles Award to a deserving senior in memory of the Class of 1851 alumnus.

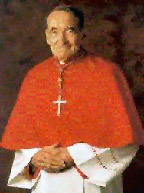

The cleric's other son also rose to high office: John Foster Dulles (above), Secretary of State from 1953 until his death in 1959. The careers of John Foster's brother, Allen Watson, and their sister, Eleanor, also included extensive diplomatic service, a family tradition.

Their grandfather John Watson Foster and their uncle Robert Lansing had both served as Secretaries of State. John, Allen and Eleanor's mother Edith was John Watson Foster's daughter; Edith's sister was their aunt Eleanor Foster Lansing. Grandfather Foster and Uncle Lansing were major forces in lives of the minister's children. So was the Auburn area.

On June 26, 1912, John Foster Dulles and Janet Pomeroy Avery, daughter of a prominent Auburn attorney and former federal official, Charles Irving Avery, were married at Auburn.

Of John and Janet's three children, the one attaining world wide name recognition that seems part of the Dulles heritage is Avery Robert, born Aug. 24, 1918 in Auburn. His field is theology as was his grandfather's but at seemingly opposite ends.

The Rev. Allen Macy Dulles was part of the Auburn Affirmation movement, hailed as liberal, open and inclusive by supporters; denounced by its critics as modernist, undoctrinal and anti-scriptural. Son John Foster advocated Auburn Affirmationist views in Presbyterian disputes.

Despite having been exposed within the family to this particular view of faith, or perhaps because of that exposure, Avery entered Harvard as an avowed agnostic.

But his studies of medieval art, philosophy and theology started an intellectual journey that became a spiritual odyssey resulting eventually in his conversion to Catholicism.

Later, after Naval intelligence service during WWII (for which he won the Croix de Guerre) and after contracting polio in Naples, he returned to the U.S. to resume studies and became a Jesuit priest and Fordham University professor.

Father Dulles' books, articles and lectures have earned him standing as the preeminent Catholic theologian in the U.S.

He has served as president, not only of the Catholic Theological Society of America, but also the American Theological Society, founded by a group of Protestant theologians including his grandfather.

In February, 2001, the grandson of Auburn Affirmationist Allen Macy Dulles becameCardinal Avery Dulles (below) , first U.S. theologian to be named to the College of Cardinals, as well as the first American Jesuit so honored.

[Image selection & caption by NYCHS webmaster]

Keepers detained prisoners by a rigid system of discipline which forebade all communication between convicts at any

time, day or night, held every man to his proper place, exacted compliance with every requirement and promptly

punished any infraction of the rules.

Administrators agreed that their most important task was to break the convicts spirit; to bring him to a state of utter

submission, and then force him to work. Breaking his spirit was the only way to keep an inmate in line and make

sure that he would conform to the unnatural discipline demanded by a system of silence, solemnity and order.

Early administrators honestly believed that a doctrine of severity to all was necessary. In accordance with the

Calvinist belief in the depravity of man, they concluded that all prisoners were scoundrels to be subdued and exploited

in the work shops to earn their keep and hold down the expenses of operating the institution. New York State was a parsimonious state and taxpayers were

unwilling to spend much money on maintaining prisons.

Soon after entering the hostile environment of the prison students learned to suppress their natural youthful exhuberance. They realized that

the climate of the institution presented a serious challenge that they must overcome if they were to be of service to members of the

population. Prison was a humorless place where normal interaction between students and convicts was not only frowned upon, it was

emphatically forbidden.

Students adjusted their conduct accordingly; they did their best to obey prison rules while carrying out their mission to bring the words of the

gospel to persons in need of redemption. The seminarians believed that there was a place for religious education of the men in the prison,

regardless of the legal reasons for their confinement. Back in the seminary they were held to high standards of self-control; they maintained

that control over their emotions while inside the prison walls.

Under any circumstance religion exerts a happy influence. Inmates attending sabbath school regardless of their initial reason for being there,

soon became attentive and interested pupils where some, perhaps for the first time in their lives, listened to the precepts and promises of the

bible.

On February 1, 1826, Gershom Powers was appointed Warden and Agent of Auburn Prison. He was a man of strong religious convictions.

For his time he was an enlightened warden. Satisfied with the evidence of moral improvement and the more worthy direction of thought and feeling demonstrated by the 50 convicts involved in the first year of the sabbath school, he doubled the number in the second

year.

At Powers' insistance the position of a paid, full-time, resident chaplain was created in 1827, an innovation in prison administration. Reverend Jared

Curtis served as the first chaplain in a prison in the United States. He received a salary of $200 per year while the guard at the front gate was paid

$216.

Powers had strong feelings about the position of and the need for a chaplain. As reported in the Second Report of the Prison Discipline Society, he

said:

"A resident chaplain, possessed of those qualifications by which he ought to be distinguished; having a thorough knowledge of mankind;

prudent, firm, discrete, and affectionate; activated by motives of public policy and Christian benevolence; will very readily secure the respect and

confidence of a majority of the convicts. Residing with them, and visiting their solitary and cheerless abodes, they will consider him, especially the

young, their minister, their guide, their counselor, and their friend."

In the early days the chaplain's success was usually measured by the number of conversions he was able to record. The actual number of

conversions, however, was difficult and almost impossible to ascertain while the men were still in prison. Who was truly repentant was not known.

All inmates attending sabbath school and religious services were not equally affected. Some were in denial and preferred to protest their innocence

rather than admit their guilt for violating the law. Under such circumstances it was difficult to reach the conscience and convey the message of the Gospel which demands,

in the first place, repentance and the confession of sin.

Others who acknowledged their crime professed a desire to turn from sin to a virtuous way of life with different degrees of sincerity and

earnestness. Still others, while pretending to be sincere, were actually unwilling to make any change in their lives.

In 1828 the number of students in the seminary grew to 76 with the number of faculty members growing also. The inmate population now

numbered over 600 men. The sabbath school was in a flourishing state with a competent teacher from the seminary for each group of five or six

individuals working under the guidance of chaplain Curtis who was immensely pleased with the functioning of the program.

Seminary students who studied the relationship between God and mankind on campus continued to seize the opportunity to obtain practical

experience in dealing with the anti-social men incarcerated in the prison. However entry to the prison wasn't always easy or automatic.

Sometimes volunteers had to wait outside of the front gate until convict assembly inside was completed. Some keepers resented the intrusion

of the seminarians for they had to do extra work patroling galleries and unlocking doors of those inmates who desired to attend services.

Otherwise Sunday would be an easy day for keepers who could rest while the inmates were locked in their cells.

|