|

On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application in France By Gustave de Beaumont & Alexis de Tocqueville ["The order of one day is that of the whole year."]

. . . . We may say, however, that if in the prisons of Auburn, Sing Sing, Boston, and Wethersfield, silence is not always strictly observed, the cases of infraction are so rare that they are of little danger. Admitted as we have been into the interior of these various establishments, and going there at every hour of the day, without being accompanied by anybody, visiting by turns the cells, the workshops, the chapel and the yards, we have never been able to surprise a prisoner uttering a single word, and yet we have sometimes spent whole weeks in observing the same prison. In Auburn, the building facilitates in a peculiar way the discovery of all contraventions of discipline. Each workshop where the prisoners work, is surrounded by a gallery, from which they may be observed, though the observer remains unseen. We have often espied from this gallery the conduct of the prisoners, whom we did not detect a single time in a breach of discipline . . . . There is moreover a fact which proves better than any other, how strictly silence is observed in these establishments; it is that which takes place at Sing Sing. The prisoners are there occupied in breaking stones from the quarries, situated without the penitentiary; so that nine hundred criminals, watched by thirty keepers, work free in the midst of an open field, without a chain fettering their feet or hands. It is evident that the life of the keepers would be at the mercy of the prisoners, if material force were sufficient for the latter; but they want moral force. And why are these nine hundred collected malefactors less strong than the thirty individuals who command them? Because the keepers communicate freely with each other, act in concert, and have all the power of association; while the convicts separated from each other, by silence, have, in spite of their numerical force, all the weakness of isolation . . . . We have seen the elements of which the prison is composed. Let us now examine how its organization operates. When the convict arrives in the prison, a physician verifies the state of his health. He is washed; his hair is cut, and new dress, according to the uniform of the prison is given to him. In Philadelphia, he is conducted to his solitary cell, which he never leaves; there he works, eats, and rests; and the construction of this cell is so complete, that there is no necessity whatever to leave it.

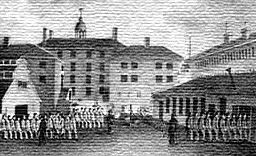

At Auburn, at Wethersfield, and in the other prisons of the same nature, the prisoner is first plunged into the same solitude, but it is only for a few days, after which he leaves it, in order to occupy himself in the workshops. With daybreak, a bell gives the sign of rising; the jailors open the doors. The prisoners range themselves in a line, under the command of their respective jailors, and go first into the yard, where they wash their hands and faces, and from thence into the workshops, where they go directly to work. Their labor is not interrupted until the hour of taking food. There is not a single instant given to recreation. At Auburn, when the hours of breakfast or of dinner have arrived, labor is suspended, and all the convicts meet in the large refectory. At Sing Sing, and in all other penitentiaries, they retire into their cells, and take their meals separately. This latter regulation appeared to us preferable to that at Auburn. It is not without inconvenience and even danger, that so large a number of criminals can be collected in the same room; their union renders the discipline much more difficult. In the evening, at the setting of the sun, labor ceases, and the convicts leave the workshops to retire into their cells. Upon rising, going to sleep, eating, leaving the cells and going back to them, everything passes in the most profound silence, and nothing is heard in the whole prison but the steps of those who march, or sounds proceeding from the workshops. But when the day is finished, and the prisoners have retired to their cells, the silence within these vast walls, which contain so many prisoners, is that of death. We have often trod during night those monotonous and dumb galleries, where a lamp is always burning: we felt as if we traversed catacombs; there were a thousand living beings, and yet it was a desert solitude. The order of one day is that of the whole year. Thus one hour of the convict follows with overwhelming uniformity the other, from the moment of his entry into the prison to the expiration of his punishment. Labor fills the whole day. The whole night is given to rest. As the labor is hard, long hours of rest are necessary; it is not denied to the prisoner between the moment of going to rest and that of rising. And before his sleep as after it, he has time to think of his solitude, his crime and his misery. All penitentiaries it is true have not the same regulations, but all the convicts of a prison are treated in the same way. There is even more equality in the prison than in society. All have the same dress, and eat the same bread. All work; there exists in this respect, no other distinction than that which results from a greater natural skill for one art than for another. . . .

Their food is wholesome, abundant, but coarse; it has to support their strength, but ought not to afford them any of those gratifications of the appetite, which are agreeable merely. None can follow a diet different from that of the prison. Every kind of fermented liquor is prohibited; water alone is drunk here. The convict who might be possessed of treasures, would nevertheless live like the poorest among them; and we do not find in the American prisons, those eating houses which are found in ours, and in which the convict may buy everything to gratify his appetite. The abuse of wine is there unknown, because the use of it is interdicted. . . . Application to labor and good conduct in prison, do not procure the prisoner any alleviation. Experience shows that the criminal who, while in society, has committed the most expert and audacious crimes, is often the least refractory in prison. He is more docile than the others, because he is more intelligent; and he knows how to submit to necessity when he finds himself without power to revolt. Generally he is more skillful and more active, particularly if an enjoyment, at no great distance, awaits him as the reward of his efforts; so that if we accord to the prisoners privileges resulting from their conduct in the prison, we run the risk of alleviating the rigor of imprisonment to that criminal who most deserves them, and of depriving of all favors those who merit them most. Perhaps it would be impossible, in the actual state of our prisons, to manage them without the assistance of rewards granted for the zeal, activity, and talent of the prisoners. But in America, where prison discipline operates supported by the fear of chastisement, a moral influence can be dispensed with in respect to their management. |