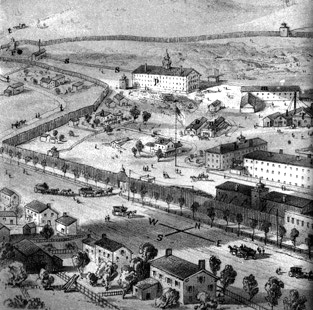

Enlargement of the left side of the NYCHS scan of the Clinton Prison

illustration in the 1869 State Senate documents volume.*

(part 2: the prison mine plan) |

||||||||

|

by Ron Roizen

Among the most ambitious of these -- and the most popular - was the suggestion to use prisoners for the mining of iron ore. It served the double function of feeding the resources appetite of an increasingly industrialized economy and sparing citizen-artisans from further competition. By authority of the penal law of 1842, Ransom Cook was commissioned to find an appropriate deposit of ore. In 1843, Cook presented an enthusiastic report, stating that he had located a tract of land seventeen miles west of Plattsburgh which was capable of being mined with comparative ease and possessed favorable access to fuel supplies for smelting. We can imagine that, if for no other reasons than the sheer distance to and isolation of this site, constituencies were gladdened. Quickly, the building of Clinton prison was began; its site was named Dannemora after a well-known Swedish iron center.

Cook became the first warden of the institution, but his high hopes for it were not realized. A change of administration in the board of prison inspectors brought Cook's removal in 1848. A change of wardens, however, did nothing to improve matters. Remote from the state's major centers of population and connected with the outside world only by the poorest of roads, the institution could not market its products effectively and was expensive to provision with food and other supplies. . . . initial estimates of the ore contained in the penitentiary tract proved overly sanguine.

Critics demanded the desertion of the beleaguered prison, but Sing Sing and Auburn were too crowded to accept the transfers, and the abandonment of Clinton was seen as politically unwise. The institution remained open, although In 1860, Governor Morgan told the legislature that the "disproportionate cost of maintaining the prison at Dannemora . . . shows that its original design and location there was an error." (ND, p. 262) The system of state use became the fall-back position of prison administration. Modest returns to contract labor served to return Sing Sing and Auburn to minimally self-sufficient incomes by 1861, but the burden of the penitentiary at Dannemora caused the system as a whole to show a net loss. (ND, p. 267) Demoralized and often idle, the prison scene of the 1850s was one of frequent violent outbreaks and increasingly harsh prison discipline. The penitentiary institution was hamstrung by extrinsic factors such that it could neither occupy its inmates nor support itself adequately. In 1859 the legislature made appropriations for the expansion of Clinton from 390 to 544 cells. Contract labor for the production of shoes, boots, and cooper wares occupied a small number of men while the majority mined or worked on new construction. In 1864, the Inspectors of the State Prison reported that[:]

The Inspectors suggested that the institution be employed in the manufacture of iron and nails for the State. In July 1865 the inmate population was turned to this task. From 1865 to 1868, the Inspectors reported a net profit for the institution, and "state employ" was strongly recommended to other institations. For the next eight years, however, budget deficits swelled. Fires in 1874 and 1875 destroyed a coal stockpile, a barn, a large portion of the prison pickets, stores, and eleven head of cattle. A new crew of Inspectors reported in 1876 that[:] the manufacture of iron and nails at Clinton prison has proved a disasterous failure as a financial undertaking. (C, p. 4) They argued that the Clinton inmate population could be supported "in absolute idleness" for a third the cost of that expended on the underwriting of iron and nails. Clinton was ordered to shed ballast -- the production equipment was sold, lands were sold, indeed the capital stock of the prison was put out for auction. Contract labor was deemed the new direction. |

| <-- previous | next ---> |