|

[Part 2 of 2]

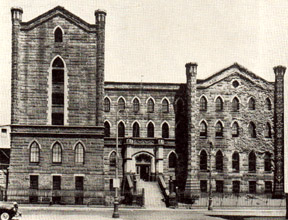

Raymond St. Jail that closed July 20, 1963. Photo from Page 36 of NYC Dept. of Correction 1956 annual report. The starting days of the second trail of Lyman Week's alleged killer John Greenwall-- Jan. 15 and 16, 1889 -- drew only headline-less, one-paragraph items on successive days in a New York Times column of sundry Brooklyn news bits. But the re-sentence of Greenwall to be hanged drew a fair-size Jan. 23rd story headlined Second Death Sentence. Greenwall's attorney C. F. Kinsley advanced the interesting argument that the defendant couldn't be sentenced to be hanged by Kings County since the legislature had decreed all executions were to be carried out by the state using electricity and the defendant also couldn't be sentenced to be executed by the state using electricity because the crime had taken place before the electrical execution law had taken effect. |

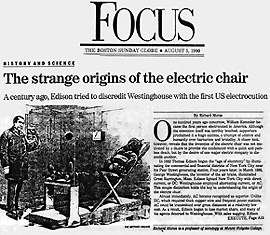

A gibbet -- perhaps similar to the example shown above from Genesee County, N.Y. -- apparently was employed in hanging executions at Brooklyn's Raymond Street Jail and NYC's Tombs. Such a device was operated by using a counter weight, which when released, caused the rope to pull the noosed condemned criminal up with such sudden force as to break the neck (if done correctly). When done incorrectly -- as in the 1884 execution of Alexander Jefferson at the Raymond St. Jail -- the neck did not break, the condemned man slowly strangled to death. His agonized sounds and violent motions turned what was meant to be a solemn event into a horror show. Such occurrences prompted authorities to seek a more humane method. They were persuaded the electric chair fit that purpose. |

||||||||||||||||

|

Judge Henry A. Moore expressed doubt that the legislators had intended to exempt from county-administered capital punishment those convicted of first degree murders committed prior to Jan. 1, 1889, the date the lawmakers selected for the law authorizing state executions by electricity for convicted first degree murderers to take effect. Commenting that the Court of Appeals could sort out the issue if the question got that far, the judge again sentenced Greenwall to be hanged at the Raymond Street Jail.

Another factor in the Court of Appeals Oct. 8, 1889 decision was the substantially weaker defense mounted in the second trial. Missing was the first trial defense's key witness: Frank "Butch" Miller. He had been indicted with Greenwall but his testimony implicated Paul Krauss. For the retrial, Miller wasn't called by either the defense or the prosecution even though he was sitting in the nearby Raymond St. Jail. One can only speculate about why the defense didn't call upon him again. Perhaps knowing what happened later to the Weeks burglary-murder charges against Miller may be useful in pondering his no-show the second time around. Those charges were dropped by DA Ridgway. The New York Times Oct. 9, 1889, story reporting the high court's decision concluded with the following bit of background information: "Butch" Miller, charged with complicity in the crime, was recently discharged, the District Attorney not having sufficient evidence upon which to convict. One may wonder where, when and what kind of insufficiency developed in the evidence that had been strong enough to result in two guilty verdicts against Greenwall, given that the same evidence identified and implicated Miller. Indeed the weight of the identification testimony by the three eye-witnesses -- Chamberlain, Dixon and Atwood -- was even stronger against Miller because of his distinguishing physical characteristic: a hump on his back. Would it be overly cynical to suspect that (a) Miller not appearing as a defense witness at the retrial and (b) the prosecution's later dismissal of the charges against him were directly connected . . . . as in quid pro quo? Yet not content simply with Miller's non-appearance at the retrial, DA Ridgway attempted in his summation to use that non-appearance as a form of testimony favorable to the prosecution. Justice Earl's Oct. 8th opinion described what happened at the retrial: The defendant was a witness upon his own behalf, and during his cross-examination the district attorney said, in the presence and hearing of the jury: "I convicted the defendant before, and I will do it again." The defendant's counsel immediately arose, and, addressing the court, said "That reference to the former conviction is a violation of law, and I ask it become a matter of record in this court." This the court [trial Judge Moore] then declined, but it was subsequently made part of the record.

"Ask Butch Miller, the man who is jointly indicted with the defendant for the murder of Mr. Weeks, where he was on the night of the 15th of March, 1887, and see if he won't tell you he was on De Kalb avenue, and opposite the Weeks house. "Ask Butch Miller if he was not in the saloon where Dr. Atwood said he saw them both. "Ask Butch Miller if he did not take the car of which [Dixon] was the conductor, and ride to the ferry after twelve o'clock on the night in question. "Ask Miller if he did not cross [on] the ferry at the time and place as testified to by Mr. Chamberlain. "The gentleman on the other side used him as a witness, and profited by the experience." Miller was not a witness upon this trial, but seems to have been a witness for the defendant upon the former trial. For the use of the language quoted, and upon other grounds, the defendant before judgment moved for a new trial, which was denied [by Judge Moore]. The language of the district attorney first quoted was improper, and it may have been a technical violation of section 464 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which provides that, upon the new trial after the reversal of a former conviction, 'the former verdict cannot be used or referred to, either in evidence or on argument.' But we do not know under what precise circumstances the language was used, nor what prompted it. So the words used by the district attorney in his summing up should not have been spoken. But the attention of the court was not called to them, and no objection was made to them at the time. The whole address of the district attorney is not given, and thus we have not before us the context, and are unable to see how, if at all, the words were qualified. The judge very emphatically charged the jury that they must base their verdict exclusively upon the law and the evidence, and, if the charge was not sufficiently explicit in this respect, it would undoubtedly have been made so if he had been properly requested. If the intemperate remarks of the prosecuting attorney in criminal cases, made in the heat and excitement of the trial, and sometimes under the provocation of language used by counsel for the defendant, may always be the foundation for a new trial, the administration of criminal justice will become very uncertain. The district attorney representing the majesty of the people, and having no responsibility except fairly to discharge his duty, should put himself under proper restraint, and should not, in his remarks in the hearing of the jury, go beyond the evidence, or the bounds of a reasonable moderation. The presiding judge can, however, control intemperate language, or so guide the minds of the jury that it may not have injurious effect. If, however, this court can see that the defendant has been prejudiced by such language, it has power, under sections 527 and 528 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, to order a new trial. But before a new trial should be ordered upon such a ground the court should be satisfied that justice requires it. Here the trial judge, who heard all that was said and done upon the trial, refused to grant a new trial, and we are satisfied that justice does not require a new trial, and the defendant has no absolute right to a new trial. Two juries, upon substantially the same evidence, have passed upon his case with the same result. There can be no reasonable doubt of his guilt, and the judgment should be affirmed. All concur.

That Judge Moore and DA Ridgway worked closely together as part of the McLaughlin political machine as well as part of the Brooklyn legal system does not necessarily mean they would ever allow their political ties to influence the performance of their duties in the criminal justice system. But just such a suggestion was raised about them by the New York Times. Brooklyn Grand Jurors investigating alleged government corruption had sought in December 1892 and in March, April, and June of 1893 to bring charges against high municipal officials but had been told by the DA they lacked jurisdiction to do so because the charges were misdemeanors, the sole jurisdiction of which Ridgway claimed rested with Sessions Court headed by Judge Moore who backed the DA's interpretation of the applicable law on the question.. Frustrated by the Ridgway-Moore stance that effectively shielded Brooklyn's mayor, various aldermen and others from prosecution, the June 1893 grand jurors issued a stunning presentment that declared:

The Grand Jury sincerely regrets its inability to present an indictment against these members of the Board of Aldermen and His Honor the Mayor, but under the law, as interpreted by the learned District Attorney, we find ourselves precluded from doing so. Despite the ceremonially deferential language, the Grand Jury presentment was a resounding slap in the face for Ridgway and, by extension, Moore. It blew their cover in trying to keep a lid on the Grand Jurors anti-corruption efforts. At least the Times saw it that way. It's very long, election-eve Nov. 5, 1893 story read, in part: The New York Times revealed that the District Attorney and Judge Moore had assumed extraordinary privileges in regard to the Grand Jury . . . . Judge Moore, according to a member of the June Grand Jury, went into the Grand Jury room to give them an interpretation of a special statute as to misdemeanors, agreeing with the opinion of the District Attorney. . . . Interviews with . . . other eminent lawyers, obtained by The New York Times, showed a unanimity of judgment adverse to the course pursued by the District Attorney. The reported consensus apparently was to the effect that the cited statute didn't really preclude the Grand Jury from acting in misdemeanor matters not then already before the Sessions Court and that, in any event, a way could have been found for bringing the misdemeanor charges sought by the Grand Jury -- if the DA and the Sessions Court judge had really wanted to work the will of the jurors. Assessing the validity of the arguments aired in the controversy surrounding Ridgway and Moore's actions allegedly thwarting the Grand Juries' anti-corruption efforts more than a century ago falls beyond the scope of this web essay. But their political and legal teamwork is worth noting as background. It gives one pause to ponder the Court of Appeals' reliance on the trial judge to have made an objective evaluation of the prejudicial impact that the DA's improper and intemperate summation remarks may had upon the jurors as they were about to begin deliberations. From this great distance in time, to attempt to answer that question -- whether the high court's pro forma deference to the trial judge was misplaced in this particularly sensitive and high profile capital case with this particularly aggressive and ambitious prosecutor -- would be foolish. But one would also be foolish not to recognize that the question arises, and lingers as a dark presence, from reviewing Moore and Ridgway's handling of the Weeks murder case as well as from reading reports of their political machine ties and teamwork. A separate issue is the questionable but apparently standard practice of that era permitting Judge Moore -- who in sentencing Greenwall after the first trial had expressed himself "personally satisfied" with the verdict and whose first trial rulings led to the verdict being vacated -- to preside at the retrial.

Also not availing was the strange attempt of a Raymond St. Jail porter Joseph Jackson to persuade a prosecution witness, the burglar John Baker, to cease backing fellow burglar Paul Krauss' story implicating Greenwall. Jackson's job cleaning and helping to maintain the Raymond St. Jai brought him into regular contact with the condemned man. The African American janitor and the German immigrant became friends. The former became convinced that the latter was innocent of the Weeks murder. With less than a month remaining before the scheduled execution, Jackson somehow got into his head the idea he could save his friend from the noose by having Baker recant his testimony. Jackson confronted Baker in Manhattan, urged him to clear Greenwall, accused him of perjury when he refused and fired a pistol at him in frustration, inflicting only a minor wound. As result, Jackson himself became an inmate -- of the Tombs. As for Krauss, he had proved himself just as resourceful, risk-taking, cunning and manipulative when locked up as a material witness in Raymond St. Jail as he did when locked up in Manhattan with Greenwall and the others for the Jersey City estate burglary. In latter situation, he was quick to extract himself by implicating Greenwall in the Weeks murder. But after testifying for the prosecution in the first trial, Krauss remained in custody during the pendency of Greenwall's appeal. About two months after Greenwall's first trial, Krauss began exhibiting symptoms associated with edema (in that era called dropsy). In August 1887, District Attorney Ridgway, concerned Krauss might become too ill to be of use if and when needed in court again, had him transferred to less restrictive quarters at the Raymond Street facility. He was moved in the Civil Jail section just five doors down from Warden Martin Van Buren Burroughs' own quarters on the fourth floor.

Warden Burroughs was a recognized member of the Kings County political machine as were his superiors, Sheriff Charles "Buck" Farley and Undersheriff Hugh "Bub" McLaughlin, nephew of the party boss also named Hugh McLaughlin. Burroughs stressed that he had wanted Krauss kept in the more secure prison section of the facility and that the escape would not have happened if DA Ridgway had not ordered Sheriff Farley to transfer Krauss to the Civil Jail section, admittedly less secure since its inmates are confined there under civil law, not criminal law. In any event, Krauss' escape was that the first since he had become warden, Warden Burroughs noted. After Greenwall's first death sentence was declared by Judge Moore the morning of May 27, 1887, the condemned man was visited that afternoon in the Raymond St. Jail by the Rev. George Unangst Wenner. A 1865 Yale divinity graduate who in 1868 founded Christ Lutheran Church over a blacksmith shop at 14th St. near 5th Ave., Manhattan (an anvil serving as its first pulpit), Rev. Wenner engaged in special outreach efforts to German immigrants. The New York Times mentioned his visit with Greenwall in the last paragraph of its next-day story on the death sentence. It reported that the pastor "talked with the prisoner for an hour and took voluminous notes, the nature of which he refused to divulge." Rev. Wenner would serve Christ Church as pastor more than 60 years, becoming in the process the dean of New York City clerics. He was a prolific author of books and essays on church-related subjects, including religious education and outreach to Lutheran immigrants. One of his published works, now available on the Internet, is a history -- century by century, era by era, immigrant wave by immigrant wave -- of Lutherans in New York City. In addition to the opportunity that the situation presented for possibly rendering spiritual service, the fact that a German immigrant was to be hanged in Brooklyn may have drawn the minister's historical interest. Given that a NYS commission was at that time studying more humane alternatives to hanging as a method of legal execution, the distinct possibility existed in the spring of 1887 that the scheduled July 15 Greenwall hanging would be one of the last, if not the very last legal execution by that method in the state. After the Court of Appeals on Oct. 8, 1889 refused to overturn the second guilty verdict and death sentence against Greenwall, his hopes to escape the noose rested chiefly with efforts to win a clemency commutation to life imprisonment from Gov. David Hill.

The governor took the position that the purported new evidence needed to be submitted to, and reviewed by the courts first before he would consider the matter. Given that the execution was slated for Dec. 6, the prospects for successfully moving the submissions through the courts prior that date were remote at best. A round-the-clock death watch was placed on Greenwall outside his Raymond St. Jail cell. The state didn't want the prisoner taking preemptive action. A young curate from nearby Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Church regularly visited with the condemned man even though the convict was not of the same denomination or national background. Inside a prison, especially on death row, those considerations seem somehow to carry less weight than they do "on the outside." Ordained a priest only five years earlier, Father John F. O'Hara had been assigned by Bishop John Loughlin to the Debevoise and DeKalb Ave. church whose parish boundaries included the jail. The distance between the jail and the church was but a few blocks walk for the cleric. For the prisoner, the distance between the whole of his past life of crime and the next hour of each of his days remaining in the face of approaching death was a wide chasm. Fr. O'Hara's visits appeared to help him to traverse it. On Nov. 29 Greenwall, who had been receiving religious instruction from the priest, was baptized by him. Keeper John J. Wilson served as the prisoner's sponsor at the "christening," becoming in effect what the New York Times termed "Greenwall's godfather." A career man, Wilson would rise through the ranks to Deputy Warden and occasionally Acting Warden under a series of wardens, most appointed without prior correction service credentials but having the right political connections. Wardens would come and go but DW Wilson would continue to oversee the day-to-day operations into the second half of the first decade of the next century. Given his virtual status as the jail's CEO in all but title, DW Wilson would be in the middle of its daily routine and much that wasn't. In all likelihood, Wilson was there to lend moral support that seventh hour of Tuesday morning, Dec. 6th, as his "godson" Greenwall struggled to maintain manly composure taking his last steps in life approaching the gibbet. The condemned man succeeded in walking to it under his own power but, as the black hood was about to be placed over his head, his face turned white and his pinioned legs trembled. At that moment, Fr. O'Hara pressed a crucifix to Greenwall's lips, and (according to the New York Times' next day story), "the latter kissed it passionately." In an instant, executioner "Little Joe" Atkinson rapped sharply on a wooden partition behind which was concealed the mechanism that released 500+ pounds of metal weights. The rap was a signal to an assistant to set the mechanism in motion. A loud crash was heard and Greenwall was jerked upward with a force that broke his neck, killing him almost instantly. There was little convulsion in the body but the customary 20 minutes of waiting was observed before the required medical check was made. Death was pronounced at 7:30. Thus ended the life of the man known as John Greenwall (aka John Greenwald and Johann Theodore Wild), a tailor by trade, a thief by reputation and a murderer according to the processes of law. Also ended were Joseph Atkinson's more than three-decade career as New York's leading legal hangman and the state's nearly two-and-half centuries of recorded use of the noose for legal executions. Twenty-seven years later, the earthly remains of the priest who had baptized NY's last condemned man to be executed by hanging were also buried in the same cemetery where he had bought a burial plot for Greenwall. The priest, by 1916 the pastor of St. Matthew's Catholic Church, Brooklyn, had died of an apparent heart attack which followed shortly after his seeming recovery from the attempt by an anarchist chef Nestor Dondoglio, identified with the Galleanist radicals, to kill hundreds of guests at a Chicago dinner for Brooklyn Auxiliary Bishop George Mundelein newly-appointed archbishop of the Windy City. Afterwards various threats against the general public were published and attributed to the Galleanists, and they were not the only radicals whose reported activities alarmed Americans in that era. The soup had been so heavily laced with arsenic that Fr. O'Hara and others who had it vomited the poison up and, although quite ill, survived. At least, so the reports went at the time. St. Matthew's rectory insisted the death of Fr. O'Hara, 56, was unrelated. But who knows whether the poisoning a few days earlier had not so weakened him that the heart attack he might otherwise survived proved fatal? So the anarchist chef, who was never caught, may have helped kill with poison the priest who had befriended the last convicted killer executed with a rope in New York State. May one ponder whether those two -- the once-Raymond St. Jail chaplain and his convert, the executed convict -- now sharing an East Flatbush cemetery as their earthly remains address, ever get to discuss with each other the ironies of human history, especially as seen from eternity? Among the ironies available for them to discuss are

| |||||||||||||||||