Although I didn’t know it then, at the end of the sixties, my father had less than a decade left to talk to me. By early 1977, arteriosclerosis had stolen his mind. I not only lost my dad, I lost the only person who could tell me about his life in prison.

In the years that followed until his death in 1981, he told me little else about his life in Sing Sing and I, fearing I might hurt his feelings, spoke of it no more than two or three times. I remember what was said, but not when or where we talked.

I know there were many other moments when I wanted to inquire about what Dad did in prison and how he spent his sentence of five years, but I simply didn’t have the heart to open up the subject or ask the questions. I probably was right not to probe into what must have been painful memories for my dad, but all my life I have regretted the lost opportunity to know what happened to him in Sing Sing.

Eventually, I did discover the reason for the robberies that lead to his incarceration. My father told me he had robbed to pay off gambling debts he owed the New York City mob. Knowing him, his explanation was easy to both believe and understand.

Formerly the Fannie Gold & Son candy store.

84 Croton Avenue, Ossining, former home of Fanny Gold & Son Confectionary.

[Photo courtesy of author.]

|

|

A life-long “losing” gambler, my dad was constantly in debt to shylocks and the Household Finance Company.

As a child I well remember living in dread of an HFC moving truck arriving at our rented apartment to take away our furniture. No such truck ever arrived, but I never stopped worrying about it until years later when I was in college.

Dad also borrowed money from other gamblers, friends, family, and anyone else foolish enough to loan him anything.

I once saw a long list of his debts in a small notebook he kept in his bedside table and there were two pages and at least sixty names written in his bold handwriting. Beside each man’s name was the amount of the debt and the date it was borrowed.

Despite all my father’s good intentions, I think he rarely, if ever, repaid the loans.

With the exception of his mother, who would have given him her last dollar, he never borrowed money from women. As a man’s man, that was not permitted within his personal code of behavior. But Dad had no such scruples about asking his sons for money and, over the years, he must have “borrowed” hundreds of dollars from me and thousands from my brother.

We always would give him some or most of what was requested unless Dad told us he was in a “swindle.” Then, we gave him all he needed. Though Mike and I never discussed it with each other, we knew “swindle” was his word for money he had taken out of the cash register where he worked.

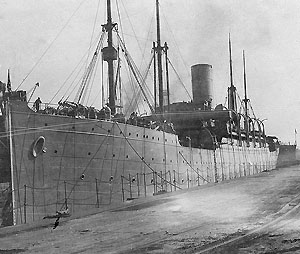

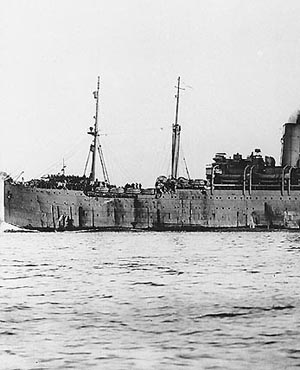

Harry N. Gold's WWI service ship docked.

Harry N. Gold's WWI service aboard the USS Antigone figured into his sentencing.

Images of the ship did not appear in the Historian article but can be found on the web site of the Naval Historical Center. Click the above cropped image from that site to access the Naval Historical Center web page devoted to USS Antigone.

|

|

It was, of course, money Dad lost playing cards or dice and had to be returned to the register. My brother and I understood the swindles (borrowed money) was theft, even if only temporary, well before we learned with certainty that he had been in prison.

We both suspect my father “borrowed” money from wherever he worked, but we don’t know if he ever got caught, as they say, with his hand in the till. I do know, in the early sixties, he was let go by Macy’s, where for years he had been a popular and productive salesman-manager of the hobby department.

My dad said it happened because he had argued too strongly against the reduction of sales people in his department. But I doubt that explanation, especially since Dad was always a loyal employee who worked well beyond what was required or requested of him. I believed then, as I do now, Dad was fired for some “swindle” he didn’t return soon enough.

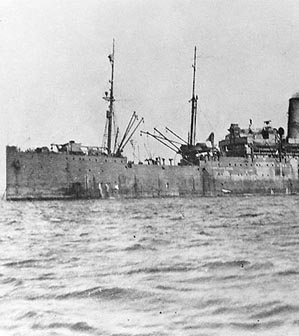

Harry N. Gold's WWI service ship in harbor.

[Left half of a Naval Historical Center image.]

Harry N. Gold's WWI service aboard the USS Antigone figured into his sentencing.

Images of the ship did not appear in the Historian article but can be found on the web site of the Naval Historical Center. Click the above cropped image from that site to access the Naval Historical Center web page devoted to USS Antigone.

|

|

In the twenties, threatened with a beating and broken legs if his loan wasn’t satisfied, my father became a stick-up man, as he termed himself, in New York City.

Despite many fictional stories describing the murder of welshers, gangsters typically used fear or physical punishment to collect their

debts. There was no sense in killing someone who owed them money, especially while there was still the possibility of payment. As a petty welsher, Dad feared the beating and broken legs, not his murder.

I don’t know the amount of money he owed the mob, but it must

have been much more than he could borrow or take from a till. It was obviously even more than he could ask from his mother. Without any other sources of money to settle his debt with the mob, my dad decided to rob retail stores in New York City.

At the time, my dad and his younger brother, Al, known in the family as “The Kid,” operated a store purchased by my grandmother in the tiny village of Ossining, New York.

Called Fannie Gold and Son Confectionary, it was one of those stores, so typical of those times, that sold candy, ice cream, magazines, newspapers, sporting goods, stationary, tobacco products and toys. A soda fountain made the store popular with the teens who attended high school across the street.

Harry N. Gold's WWI ship in harbor.

[Right half of a Naval Historical Center image.]

Harry N. Gold's WWI service on the USS Antigone figured in his sentencing.

Images of the ship did not appear in the Historian article but can be found on the web site of the Naval Historical Center. Click the above cropped image from that site to access the Naval Historical Center web page devoted to USS Antigone.

|

|

According to what my cousin, Marian (Al’s daughter), remembers her mother saying, the Ossining business was bought “to keep Harry out of trouble.” Ironically, the new store stood on Croton Avenue, only several blocks from Sing Sing Prison, where my father soon would be incarcerated.

Although Dad never described how he went about his robberies in New York, I assume he took the train to Grand Central Station and then rode the subway to lower Manhattan. He did not own a car and never would have paid a taxi to take him downtown.

I know little about the robberies themselves. According to the terse description my father gave me, he simply had walked into several small retail stores, pulled out a pistol, and robbed them at gunpoint. I do not know the number or names of the stores he held up.

Eventually, Dad was captured, but I never heard exactly how or where it happened; my father said only that he was arrested amidst a robbery and surrendered without a struggle. Since he said nothing about it, I doubt Dad ever fired the pistol.

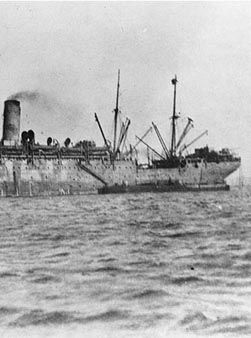

I remember only a few more details of the events that led to his conviction and imprisonment. My father told me he got a light sentence because he was a veteran of World War I. He had been in the navy serving on the Antigone, a troop-transport ship carrying American soldiers across the Atlantic to the trench-war in France.

Harry N. Gold's WWI ship

with troops aboard.

[Left half of a Naval Historical Center image.]

Harry N. Gold's WWI service aboard the USS Antigone figured into his sentencing.

Images of the ship did not appear in the Historian article but can be found on the web site of the Naval Historical Center. Click the above cropped image from that site to access the Naval Historical Center web page devoted to USS Antigone.

|

|

I do remember him telling me that my tough old grandmother, Fanny, who called her favorite son, “Mein Harry,” hired the most expensive attorney she could afford to defend him. It was assumed the “most expensive” would be the best attorney. I have no idea where my grandmother got the money, but she found it somewhere, no matter what sacrifice was required.

Her sacrifice for him is not surprising, knowing what she had done to support her two sons when my grandfather, Mechel, died of tuberculosis in 1910. For years, in all weather, she stood at a street-corner kiosk in New York selling candy, cigars, cigarettes, daily newspapers, and magazines.

She stationed herself downtown near an office building in the financial district and stayed there thirteen hours a day, six days a week. Not only did my grandmother provide for her family’s everyday needs, but, by 1922, she somehow had saved enough money to buy the store in Ossining.

Despite her triumphs over adversity, which I had heard about all my childhood, I disliked my grandmother. I saw her as cold and foreboding, a man-like woman, who seemed devoid of affection. I can’t recall her ever kissing or hugging me.

What I do remember was her sneer and contemptuous “Who you?” whenever I dared argue with her. Hearing those words, I can remember gritting my teeth to keep from saying I hated her.

Harry N. Gold's WWI ship

with troops aboard.

[Right half of a Naval Historical Center image.]

Harry N. Gold's WWI service aboard the USS Antigone figured into his sentencing.

Images of the ship did not appear in the Historian article but can be found on the web site of the Naval Historical Center. Click the above cropped image from that site to access the Naval Historical Center web page devoted to USS Antigone.

|

|

I disliked my grandmother, most of all, because of her verbal abuse of my mother, whom she had no hesitation saying was not good enough for her Harry.

Although my mother stood by him through all the Sing Sing years, countless numbers of gambling losses, and who knows how many of his swindles, she never earned my grandmother’s approval.

And, whenever my mother dared speak her mind, she too got the hated “Who you?” from the old woman. Dad, however, could do no wrong, even though his endless gambling cost my grandmother thousands of dollars and at least one life-savings I heard about.

I don’t know if, before his arrest, my father re-paid any or all the money owed the mob, but I doubt it. I have a vague memory of him saying his imprisonment absolved him of all the debt that remained. I do know he never again borrowed money from the mob.