|

If reform-minded Lewis E. Lawes had not been warden, inmate Charles Chapin could not have become "The Rose Man of Sing Sing." The excerpts from James McGrath Morris' book about Chapin reflect how prison reform literally flowered under Lawes' guidance. These excerpts and the other texts in this NYCHS presentation are not offered as a full portrait of Warden Lawes but as brief biographical references, outlines and sketches related to that extraordinary correction professional and humane human being. NYCHS appreciates the permissions granted by the acknowledged sources for the materials this presentation uses.

NYCHS excerpts from Chapter 1- The Gardens:

The Rose Man of Sing Sing:

A True Tale of Life, Murder,

and Redemption

in the Age of Yellow Journalism

By James McGrath Morris©

. . . . Before he won his manumission from the tyrants who ruled the newsrooms in the heyday of yellow journalism, [Irving S.] Cobb had toiled for Charles Chapin, the most accomplished, notorious, and feared city editor of them all.

XXX

XXX

|

|

JAMES McGRATH MORRIS began his career working as a journalist in the late 1970s both as a radio correspondent and a print reporter in New Mexico, Missouri, Washington, DC, and upstate New York, reporting on all levels of government from local school board meetings to the return of the Iranian hostages on the White House South Lawn.

In the late 1980s, Morris became a magazine editor and later a publisher with a small, public affairs book-publishing firm located in Washington. Called Seven Locks Press the company published such books as The Secret

Government by Bill Moyers, Waiting for an Army to

Die by Fred Wilcox, and Organizing for Social

Change by Kim Bobo.

In 1991, Seven Locks Press was sold and moved to California. Morris subsequently served as executive director of Public Interest Publications, a not-for-profit organization that helped Washington think tanks better distribute their publications.

In 1996, Morris was selected as one of 23 fellows in the Fairfax

Transition to Teaching (FTT) program operated by the Fairfax County Public Schools of

Virginia. The program, administered by George Washington University and funded by

Fairfax County, is a one-year teacher-training program similar to a medical residency.

Students are assigned to work in a high school for the academic year and take teacher

education course at night. At the end of the program, the students are fully certified and

eligible for licensing by the state.

By taking additional courses, FTT graduates earn a

Masters in Education. Following completion of the FTT program, Morris was hired to work

at West Springfield High School.

During his first year, 1997-1998, Morris was nominated

for the Sallie Mae First Class Teacher Award. In 2000, he received his Masters of

Education.

Morris’s work in American history has appeared in Civilization, Journal of

Historical Studies, Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, New Mexico

Historical Review, and Missouri Life, among other places.

In 2001 the Journal of Policy

History published Morris' history of school desegregation in Northern Virginia. In 1997 he

received the Phi Alpha Theta National Founders Day Award and in 1998 the

Throne/Aldrich Award from the State Historical Society of Iowa for an excerpt published in

Iowa Heritage Illustrated from his book Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate

Behind Bars, an updated paperback edition of which was published in 2001. His previous

book, the Grant Seekers Guide: Foundations that Support Social and Economic

Justice, was published in a sixth edition in 2003.

Morris has also written for magazines such

as the Progressive and newspapers such as the Washington Post.

He is married to Patricia McGrath Morris, a doctoral student at Virginia Commonwealth

University School of Social Work and a former Clinton Administration appointee. He has

three children.

|

“Chapin,” recalled Alexander Woolcott, a fellow Park Row escapee and one of New York’s leading drama critics of the 1920s, “was the acrid martinet who used to issue falsetto and sadistic orders from a swivel chair at the Evening World in that now haze-hung era when Irvin Cobb was the best rewrite man on Park Row and I was a Christian slave in the galleys of the New York Times.”

For two decades, until his abrupt and dramatic departure from the scene in 1918, Chapin had set the pace for the city’s vibrant evening press as city editor of Joseph Pulitzer’s Evening World. Beginning in the morning and sometimes stretching late into the night, the buildings on Park Row shook as massive presses rolled out hundreds of thousands of copies of evening editions. On any street corner, New Yorkers heading home could buy one of a dozen papers filled with news as fresh as the ink, for as little as a penny, hawked by the young peddlers known as newsies. . . . . This was the golden age of the newspaper. They were indispensable reading and definers of reality. As never before, the features of city life were mirrored in a daily pageantry of print.

In the guerrilla warfare of yellow journalism, any editor who valued his job got a copy of the Evening World within minutes of its publication. . . . The only strategy to beating Chapin would be to hire him, and Pulitzer continually feared that his nemesis William Randolph Hearst, whose checkbook seemed bottomless, would do just that.

Chapin’s professional life spanned the birth and adolescence of the modern mass media. In the 1880s, Chapin’s sensational crime reporting in the legendary world of Chicago journalism made him one of the best known apostles of what was then known as “new journalism.” In the 1890s, he arrived in New York just when the revolution Pulitzer had sparked was transforming Park Row into the epicenter of American journalism. And, as the city editor of Pulitzer’s Evening World for two decades, Chapin became the model for all city editors, real and fictional.

“Chapin walked alone, a tremendously competent, sometimes an almost inspired tyrant,” said Cobb. “His idol, and the only one he worshiped, except his own conceitful image, was the inky-nosed, nine-eyed, clay-footed god called News.” . . .

Chapin was said to have fired 108 men during his tenure. Even Pulitzer’s son was a victim. The fact that the father, who kept watch over his dominion with spies in the newsroom, remained mute when the ax fell on his son only served to elevate Chapin’s fearful reputation. . . . .

Now in late October 1924, events converged to resurrect memories in Cobb of those bygone days. The previous week, while in Montréal after a fishing trip on Lac La Peche, Cobb had lifted the receiver of his hotel telephone to hear the familiar, but distant voice of Ray Long, the editor of Cosmopolitan, calling from New York.

Long and Cobb had been friends since working as low-paid reporters for rival Midwestern newspapers twenty-five years earlier, when they only dreamed of making it big in New York. Now as editor of one of the nation’s most widely circulated general-interest magazines, Long had a budget lavish enough to afford Cobb, and he rewarded his friend with choice assignments.

“You worked under Charley Chapin,” Long said. “I heard you say once that he was one of the most vivid, outstanding personalities you ever encountered. I think there is a story in the entombing, the total eclipse behind prison walls of such a man.”

Indeed, the public memory of Chapin had faded in the six years since he had been sent to Sing Sing prison for murdering his wife of 38 years with a pistol while she slumbered peacefully in her bed. . . .

By 1924, however, Chapin, once the previously most-talked-about figure on Park Row, was rarely mentioned, even among the company of writers that Cobb kept. . . . “The physical image of him as I last had seen him, humped over his desk in the Pulitzer Building on Park Row, was growing fainter in my mind,” said Cobb.

Coincidentally, just days before Long’s call, Cobb had spotted an item in the New York Times that had also prompted him to think of his old boss. A dispatch from Ossining, New York, said that the state had published a report on what seemed to be an incongruity in conditions at the notorious Sing Sing prison. They credited, by name, the inmate who had brought about the change. It was Chapin.

|

. . . .He has adorned the gruesome place with flowers, trees and shrubs, and the yard which five years ago was desolate and littered with stones and rubbish is now a thing of beauty. The rose garden is an inspiration to dark and troubled souls. |

From Montréal, Cobb sent word to his secretary to go to Sing Sing and make arrangements for a visit. . . . A few years earlier, Chapin had refused a visit from Cobb. This time he accepted. Perhaps, Chapin wrote to a friend after the secretary departed, the visit will be “a chance for Cobb to get even for the hard knocks he had when I was his boss.”

Rose Man-related images from

another NYCHS presentation:

XXX

|

|

NYCHS' excepts from Guy Cheli's Sing Sing Prison in the Arcadia Images of America book series include from "Chapter 4: The Rose Man" six related photos.

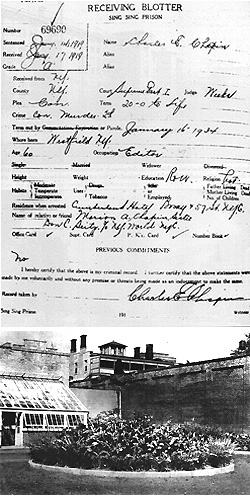

Above are two of those images:

- The Sing Sing in-take record for Charles Chapin, then 60, "occupation: editor," convicted Jan 14, 1919, for the murder of his wife.

- The Rose Man's greenhouses located behind the old warden's residence toward the river.

The other images in the NYCHS presentation of excerpts from Guy Cheli'sSing Sing Prison include his prison yard landscapes and bird sanctuary.

.

|

Although it was an overcast day, by the time Cobb set out in the late morning of October 28, 1924, it was already ten degrees above average, certainly pleasant enough to spend the day outside. Most who made the trip to the New York State Penitentiary at Ossining took the train from Grand Central Station a few blocks south of Cobb’s apartment.

For a destination as grim as it was, the trip was breathtakingly beautiful. The prison was built on the banks of the Hudson River thirty-four miles north of New York City, giving rise to the expression “being sent up the river.” The train tracks follow the contours of the river for miles, offering the passenger on the left side of the compartment an unfettered view of the Hudson, a river that inspired artists and gave rise to a school of painters . . . .

. . . . approaching Sing Sing was like coming to a medieval fortification. Erected in the 1820s with stone quarried on the spot, Sing Sing was America’s best-known and most-feared prison. Its massive stone walls, round stone towers, and heavy doors made its line of business clear to all comers. New York’s most notorious criminals were, if lucky, confined here for life or else executed on Thursdays.

Only in the prior decade had the prison begun to shed the last of its nineteenth-century practices under the rule of a new warden, Lewis Lawes. Rising from the ranks of prison guards, Lawes had been appointed by Governor Al Smith four years earlier during a wave of reform that saw many modernizations in prison life. Lawes, who dressed for the role of the enlightened reformer in tailored New York suits, enjoyed immensely showing off his fiefdom. He was publicity savvy. He knew the city’s literati—even had hopes of joining its set someday—and never missed a chance to increase his visibility and promote his reforms.

Cobb’s visit could be a boon. It also pleased Lawes that Cobb was coming to do a story about Chapin. Of all his prisoners, Chapin was one of his favorites. The two had been immediately attracted to each other when they met in 1919, and an unusual friendship had evolved. In fact, over time, Lawes had given Chapin virtual free run of the prison. On many an afternoon, the inmate could be found reading magazines in a wicker rocker on the warden’s porch overlooking the river, with the warden’s daughter playing at his feet.

. . . .Lawes escorted the writer down into the prison yard, where they found Chapin. “Dear Chief,” said the corpulent Cobb, who immediately took his old boss in his arms. Even though Chapin had gained thirty pounds and his five-foot-eight frame now held nearly 160 pounds, he was momentarily eclipsed by Cobb’s embrace. When they separated, Cobb examined his former slave master whom he had not seen since a few days before that baleful day in September 1918.

He seemed unchanged, thought Cobb. “Only he was white now when he used to be gray, with the same quick, decisive movements, the same bony, projecting chin upheld at a combative angle, the same flashes of stern and mordant humor, the same trick of chewing on a pipe stem or cigar butt, the same imperious gestures, the same air of being a creature unbendable and uncrushable.”

A Rose Man-related image from

yet another NYCHS presentation:

XXX

|

|

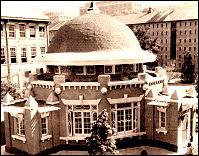

NYCHS' excepts from Mark Gado's Stone Upon Stone: Sing Sing Prison on Court TV's Crime Library web site include from "Chapter 9: The Rose Man" the above image of Chapin's Bird House at Sing Sing, circa 1929.

(Courtesy of Ossining Historical Society)

Chapin had asked Warden Lawes for permission to build a birdhouse for hundreds of birds with room for prisoners to sit and admire them.

With support from his newspaper friends and labor by inmate volunteers, Chapin guided construction to completion in three years.

The result: A magnificent structure with a huge dome and hundreds of flowers and bushes for birds to come and add to the beauty . . . all a short distance from the death house . . . .

|

But further consideration of Chapin would have to wait because what stretched out in front of Cobb were Chapin’s gardens, a certain conversation stopper.

Only a few years before, the yard—nearly as long and wide as two football fields joined end to end—had consisted of hard pack, covering decades of strewn construction debris and refuse. Only tiny of patches of struggling grass and even tinier flower beds previously broke the monotony of the gray soil surrounded on all sides by gray stone edifices. Cobb knew this landscape well because he had used the setting for one of his short stories, written eight years earlier. Now what lay before him stunned Cobb.

“There were spaces of lawns, soft and luxuriant, with flagged walks brocading them likes strips of gray lace laid down on green velvet,” he wrote. Along the walks stood soft, puffy arborvitae trees and masses of neatly trimmed ornamental shrubs. Green vines, like veins, wove their way up the walls of heavy stone, quarried by the hands of those the state had confined here for more than a century. And everywhere Cobb looked were flowers, familiar and unfamiliar, some in full bloom and others done for the year. . . .

Cobb and Chapin made their way down one of the flagstone paths. To their right, lining the bed along the six-story-tall old cellblock, was a herbaceous border 469 feet long, with more than 1,000 iris plants, 150 peonies, hundreds of other perennials, and 6,000 bulbs waiting for spring. The long narrow bed, however, served only as a complement to the massive rectangular garden running the length of the yard’s center.

At its midpoint was a fountain rising from a ten-foot-wide pool, upon the surface of which floated white and yellow water lilies. Leading to it were paths, lined with large, blue hydrangeas and benches for the inmates. And there, set in beds framed by narrow strips of lawn, were the rose bushes. They were so many as to defy counting. Chapin said they numbered about 2,000, and almost 3,000 if one counted the new arrivals in the greenhouses. . . .

Chapin’s handicraft had not stopped with the main yard. “Not an odd-shaped scrap of earth, nor a tucked-in corner behind a building or within a recess in the walls but was brilliant with flowers and grass. The eye strayed downward from wattled windows and guarded watchtowers to rest on zinnias and cannas and asters and all manner of autumnal blooms. It was like bridging two separate worlds of misery and despair, the other a world of sweetness and gentleness and hope and high intent.”

From the center, Cobb and Chapin turned and proceeded down a secondary yard. It was the only open space in the prison without a wall on every side. It gave out onto the Hudson below and was planted in solid colorful blocks. At the end of this boulevard, Cobb and Chapin turned left again and came to the most macabre building of the compound, a low-lying brick structure that contained the electric chair. Chapin’s touch was visible even here.

|

Another Correction-related book by the same author:

XXX

|

|

James McGrath Morris also authored

Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars

published in cloth cover by McFarland & Company and in paperback by Transaction Publishers.

The dramatic history of prison journalism has included many famous, notorious, and

unique personalities such as

- Robert Morris, the “financier of the America Revolution”;

- the

Younger Brothers of the Jesse James gang;

- Julian Hawthorne, the only son of Nathaniel

Hawthorne;

- men of the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW);

- Charles Chapin, famed

city editor of New York’s Evening World until he murdered his wife;

- Dr. Frederick Cook,

North Pole explorer whose claim to have been the first to reach the pole is still debated today;

- Tom Runyon, who won a place for himself in history with an Underwood; and

- Wilbert Rideau,

an illiterate teenaged murderer who raised prison journalism to the pinnacle of achievement.

|

“I saw how the approach to the new death house had been planted, so that the last outdoor thing a condemned man sees as he is marched into the barred corridor from which he does not issue again ever, is the loveliness of green grass and fair flowers,” wrote Cobb.

Next they toured a former garbage depot, now the site of Sing Sing’s prized tulip beds. In May and June, after the jonquils and hyacinths that hedged the beds quit blooming, thousands of tulips would rise in a sea of color. (The sight had become so noted that even white-gloved ladies from Westchester garden clubs braved entering this den of criminals to gaze upon it.) They traveled through three greenhouses opposite the entrance to the death house, only yards from the lapping water of the river. They were built twenty years before, when prison officials had made an attempt to have the inmates raise vegetables, and had fallen into disrepair before Chapin restored them. In winter, flowers from the greenhouse would be brought daily to the prison chapel and hospital.

Returning to the center of the prison yard, Cobb made his last stop in a fourth greenhouse abutting the old death house, in which several cells had been converted into living quarters for Chapin. Prior to its new life, the glassed-in space had been the prison’s morgue. Here, after an electrocution, the corpse was brought to be examined by state medical officials before being surrendered to the family.

After lawmakers heard of two cases in which men had been accidentally electrocuted and later revived by physicians, they passed a law requiring that the brain of execution victims be opened and examined. “On the slab where a hundred autopsies had been performed,” wrote Cobb, “potted flowers stood very thick, and in the sink where anatomists washed their tools when the job was done, sheaves of cut flowers were lying in cool clear running water.” The fragrance of the potting soil and moist plant life and the sounds of the canaries chirping in gilded cages eliminated all trace of the building’s past. . . . . Warden Lawes, who had rejoined the party, [said of Chapin:] “He’s up every morning at five o’clock and out here among these flowers and I guess he’d stay out here with ‘em all night if he could. And he’s got a whole library of books on flowers and knows ‘em all by heart.”

. . . . As they walked back toward the entrance to the yard, completing their inspection tour, Chapin continued to fill in Cobb on his new life. “Mostly we talked about his flowers, or rather he did, larding his speech with technical terms and Latin names,” wrote Cobb. “Nothing was said by either of us about repentance or atonement or regeneration or recapturing a man’s self respect. Nothing much was said about the past. Nor about the future.” But as Cobb contemplated, there wasn’t much future to talk about in the case of a sixty-five-year-old man who was serving no less than twenty years, with little prospect for parole or pardon. “He didn’t invite sympathy and I didn’t bestow it,” said Cobb. . . .

As Cobb departed, George McManus, another colleague of Chapin’s newspaper past, arrived for a visit. . . . McManus had worked on the World with Chapin a dozen years earlier. He had renounced the drudgery of Park Row when he created “Bringing Up Father,” an immensely popular comic strip starring the unflappable Maggie and her up-to-no-good husband Jiggs, whom she often chased after with a rolling pin. The strip had been nationally syndicated and recently had been turned into a Broadway play . . . . The two reminisced for a while.

Finally done with his visitors, Chapin returned to his office for the first time since the morning. There was probably no inmate anywhere in the United States, or the world for that matter, who had an office like Chapin’s. With three windows overlooking the Hudson, his carpeted, draped, and book-lined hideaway was more luxurious than any workplace he had had on the outside. There he found nine letters waiting. A prodigious correspondent, Chapin received and sent in one day the amount of mail that many inmates could hope to see in a month.

After examining the envelopes, Chapin set them all aside except for one from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. The return address alone was enough to set his old heart racing. As he already knew, it contained another installment of his newest prison-romance-by-mail begun eight months earlier with Constance R. Nelson, a young editorial worker at the bank. He feverishly read all four closely written pages . . . .

After eating supper, prepared for him by Larry, his private inmate-cook, and closing the greenhouses for the night, Chapin sat in his office as darkness and quiet fell over the prison. The other inmates were confined to their tiny, damp cells, but not Chapin. He was free to roam the dark prison all night if he wanted to. . . . He went to bed in his cell in the old death house. In the morning, he would turn 66.

Though he enjoyed unheard-of privileges for a prisoner, he was continually reminded of his descent from the life he had so relished. . . . Gone, most of all, was his power. His only remaining dominion was his rose garden. . . . . Chapin had written earlier that year . . . “Park Row would never recognize me. I don’t even know myself, and to think I have so changed in so short a time.”

“Do you think,” he asked, “do you think that growing flowers did it?”

The complete on-line text of Chapter 1 -- The Gardens from The Rose Man of Sing Sing is available, without graphics, at http://www.jamesmcgrathmorris.com/excerpt.htm

NYCHS appeciates permission from James McGrath Morris and Fordham University Press to present these excerpts. They retain all rights previously held.

More information about the book, the author, his other books and the "Rose Man" Charles Chapin can be accessed at James McGrath Morris' own site http://www.jamesmcgrathmorris.com/ and at the Fordham University Press site.

Click for audio: PBS News Hour Feb. 04, 2004 interview of James McGrath Morris about his The Rose Man of Sing Sing.

NYCHS is responsible for image selections and caption texts on this web page.

Go to

Part 1 of NYCHS' presentation of the NYC and NYS Correctional Career of Lewis E. Lawes

Go to

Part 2 of NYCHS' presentation of the NYC and NYS Correctional Career of Lewis E. Lawes

Go to

Part 3 of NYCHS' presentation of the NYC and NYS Correctional Career of Lewis E. Lawes

Also see

NYCHS excerpts - Ch. 9: Rose Man of Mark Gado's Stone Upon Stone: Sing Sing Prison

|