xxx

xxx

NYCHS presents excerpts from From Newgate to Dannemora: The Rise of

the Penitentiary in New York, 1796-1848, by W. David Lewis.

Copyright © 1965 by Cornell University; copyright renewed 1993.

Used by permission of the author and the publisher, Cornell

University Press. All rights reserved. Click on image, based on book jacket front cover, to access Cornell University Press site.

|

|

Chapter II: The First Experiment

(Part I)

(Excerpted from Pages 29 - 35)

The legislation which Thomas Eddy secured in 1796 provided

for two state penitentiaries. One of these was to be built at Albany

under the supervision of a committee which included Philip Schuyler. The other was to be constructed in New York City by Eddy

and his associates.

Less than a year later, however, the Albany plan

was abandoned, possibly because it was believed that the number

of convicts from upstate areas would be small and that one prison

would therefore suffice.

“Newgate,” which rose in Greenwich Village on the east bank of the Hudson about a mile and a half from

City Hall, was for nearly two decades to be the only institution

receiving felons convicted under the new penal code. . . .

As could be expected, Eddy leaned heavily on the experience of

Pennsylvania in constructing New York’s first penitentiary. In

April, 1796, he wrote for advice to Caleb Lownes, a Quaker iron

merchant who was an inspector of the Walnut Street jail. . . .

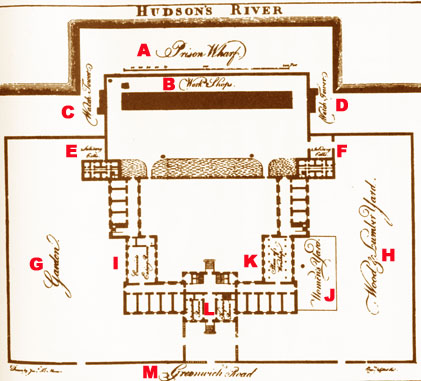

It is not surprising, therefore, that Newgate when completed

showed a considerable similarity to the Walnut Street Jail. In each

institution, two wings containing quarters for inmates extended

backward from a central structure housing administrative offices.

xxx

The image above is based on one appearing in From Newgate to Dannemora on an unnumbered page facing Page 16.

The caption reads, in part: "Ground plan of Newgate, 1797. From an engraving . . . (1801). Reprinted by courtesy of the New-York Historical Society."

Red letters have been added to this NYCHS digital version of the image to indicate the location of specific features of the facility.

|

A - Prison Wharf on the Hudson.

B - Work Shops inside prison wall.

C & D - Watch Towers.

E & F -- Solitary Cells.

G -- Garden.

H - Wood & Lumber Yard.

I - Convicts Eating Room.

|

J - Women's Yard.

K - House of Worship.

L - To left of "L" was the Inspectors Room.

L - To right of "L" was the Keepers Room.

M - Greenwich Street.

|

|

At the New York prison, solitary cells for the worst offenders were

placed in the rear portions of the wings; at Philadelphia, they

were put in a separate building altogether.At both institutions,

workshops were erected behind the main prison complex.

In some

important respects, however, Newgate was different from its Pennsylvania prototype. Unlike the Walnut Street Jail, which contained accommodations for vagrants, suspects, and debtors, Eddy’s

penitentiary was from the beginning designed and constructed

for felons only. It was also provided with a large room for public

worship, whereas the Philadelphia establishment had been built

before it was thought advisable to hold religious exercises among

criminals.

Eddy’s correspondence makes it clear that he considered Howard's

writings on prisons while supervising the construction of Newgate. Nevertheless, he disregarded Howard’s idea that it was

necessary to keep convicts in solitary confinement at night, much

to his later regret.

xxx

xxx

The Thomas Eddy image above is based on one appearing in From Newgate to Dannemora on an unnumbered page facing the title page.

The caption reads, in part: "Thomas Eddy, 1758 - 1827, New York's first significant prison reformer. From an engraving in Samuel I. Knapp, The Life of Thomas Eddy (1834). Reprinted by courtesy of the New-York Historical Society."

|

|

His decision to allow inmates to mingle even

during sleeping hours was probably influenced by the confidence

which Lownes expressed in the state of discipline at the Walnut

Street Jail, where nighttime separation did not occur except among

the most hardened or refractory prisoners.

At the completed New

York institution, most convicts were housed in fifty-four apartments with dimensions of twelve by eighteen feet, designed to

accommodate eight occupants each.

Eddy not only designed Newgate, but also became its first agent,

a position roughly corresponding to that of today’s warden. He

brought to his new assignment a philosophy which was both stern

and humanitarian.

An unsentimental man, he believed that the

prison administrator had to consider his charges as “wicked and

depraved, capable of every atrocity, and ever plotting some means

of violence and escape.”

On the other hand, he held that no two

inmates were alike, and that it would be a mistake to treat convicts

as if they had been formed in one common mold. Along with

Caleb Lownes, he believed that inmates fell into three broad categories: hardened offenders; criminals who, though depraved, still

retained some sense of virtue; and young persons convicted for the

first time. The existence of such varied types called for individualized treatment.

xxx

xxx

The image above is based on one appearing in From Newgate to Dannemora on an unnumbered page facing Page 16.

Caption reads, in part: "Front elevation ... of Newgate 1797. From an engraving . . . (1801). Reprinted by courtesy of the New-York Historical Society."

|

|

To Eddy’s mind, the reformation of the offender was the chief

end of punishment.Although he believed in the possibility of

deterrence, he regarded this as “momentary and uncertain.” Restitution might also be obtained through correctional procedures, but

the primary goal was “eradicating the evil passions and corrupt

habits which are the sources of guilt .”

In order to promote rehabilitation he encouraged religious worship and established a night

school. In the latter, he restricted the classes to the well-behaved

as an incentive to good deportment, and charged the students four

shillings’ worth of extra labor to inculcate thrift. He was disinclined to rely on fear and severity, and approved warmly of provisions in the law of 1796 which prohibited corporal punishment

at Newgate.

xxx

xxx

The image above does not appear From Newgate to Dannemora. An illustration from the period, it depicts an scene outside the penitentiary wall, looking north up Greenwich Street. Note the wall stairs. Also note two pigs in shadow at the foot of the wall. Pigs were permitted on the streets as a kind of 4-legged sanitation workers. They ate garbage left for them. Hog fill, not landfill.

|

|

His chief disciplinary weapon was solitary confinement on stinted rations, and he forbade his keepers, who were

unarmed, to strike convicts. He allowed well-behaved inmates to

have a supervised visit with their wives and relatives once every

three months, and saw that his charges were given a coarse but

ample diet.

Despite his emphasis upon humanitarian treatment, Eddy

stripped the regime at Newgate of anything resembling frills or

self-indulgence. As soon as an incoming inmate had been bathed,

provisioned, and interrogated, he was assigned to a prison shop

and made to realize that his convict life would be one of hard

work.

It took two years to complete enough shops to provide full

employment, but under Eddy’s frugal and efficient management

the penitentiary soon became a relatively prosperous industrial

unit. Shoemaking was the first trade to be inaugurated, followed

by the production of nails, barrels, linen and woolen cloth, wearing apparel, and woodenware.

xxx

xxx

The Pennsylvania coat of arms image above and the image below of the Pennsylvania Flag incorporating the coat of arms do not appear in From Newgate to Dannemora.They do appear on the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC) web site. There they help illustrate information about the design of the coat of arms for the state by Caleb Lownes, an iron merchant, a civic hero for his work combating yellow fever, and a prison reform leader to whom Thomas Eddy turned for advice. Click either image to access the PHMC site.

|

|

The program had two goals: to

promote reformation through inculcating "habits of industry and

sobriety," and to make possible an 'indemnity to the community

for the expense of the conviction and maintenance of the offender.”

By 1803, the profits of the Newgate shops actually yielded a tiny

surplus after the prison’s expenses had been paid.

It is a tribute to Eddy’s skill in handling men that he was able

to employ a working force consisting of many who were “hardened, desperate, and refractory, and many ignorant, or incapacitated through infirmity and disease,” and achieve satisfactory

results. He did this, interestingly enough, without imposing the

harsh and unmitigated slavery which later came to characterize

penal labor under the Auburn system.

Each convict at Newgate

was charged a set amount upon the prison books for his clothes

and maintenance, and accounts were kept of the proceeds from

his labor. If he compiled a good behavior record, he was given

upon release a share of the profits he had helped to earn. Inmates

who demonstrated capacity and skill were used as superintendents

and foremen in the shops.

Indeed, the inauguration of shoemaking

was made possible by a convict who had been a cobbler and who

instructed his fellow prisoners in the trade.

Despite the incentives which Eddy held out to those who conformed, it was not easy to maintain order. In 1799, guards were

forced to open fire when fifty or sixty men revolted and seized

their keepers. Several felons were wounded before the mutiny was

quelled. In 1800, the assistance of the military was necessary to

break up a riot. . . .

|

Table of Contents

|

- [Book jacket blurb, images]

- Preface

- The Heritage

- The First Experiment

- The Setting for a New Order

- The Auburn System and Its Champions

- Portrait of an Institution

- The House of Fear

- The Ordeal of the Unredeemables

- Prisons, Profits, and Protests

- A New Outlook

- Radicalism and Reaction

- Ebb Tide

- Change and Continuity

- A Critical Essay on Sources

|

|

April 4, 1803, twenty inmates tried

to scale the walls in an effort to escape. After ordering them to

desist without avail, prison guards opened fire and killed four convicts, one of whom was an innocent bystander. . . .

Some new inspectors

were appointed in 1803, and [Eddy] found himself unable to get along

with them. The root of the difficulty is not entirely clear, but it

appears that the Jeffersonians wrested control of the prison from

the Federalists. Since Eddy belonged to the latter party, political

differences may have contributed to the dissension.

The Quaker

agent also differed with his associates over economic matters, and

it is likely that the introduction of a contract labor system in the

shoemaking shop aroused his displeasure. By January, 1804, the

situation had become so unpleasant that he resigned. . . .

Late in 1805, he indicated once more that developments

at the penitentiary were not to his liking. Despite the existence

there of cleanliness and good order, he disapproved of the severity

of the discipline, and pointed out that industrial profits had declined since the days when he had been in office.

In subsequent years Newgate became more and more of a disappointment to the state, and Eddy’s pessimism was vindicated. . . .

. . . To say this is not to detract from

Eddy’s stature as a prison reformer, nor unduly to criticize those

who had helped him to establish the penitentiary, but rather to

affirm that these men were not omniscient. Some things had to

be learned from experience.

|