The indignities to which it was alleged women were subjected in the police stations and prisons of the City of New York, in which at that time no matrons were employed, of such a nature that they cannot well be mentioned here, induced Mrs. Lowell, in the spring of 1886, to request Dr. Annie S. Daniel to make an investigation and to report to her the findings.

XXX

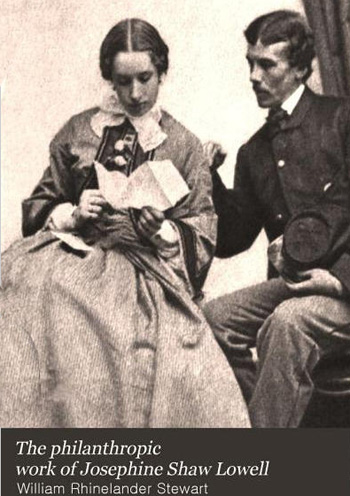

Google Books cover for Josephine Shaw Lowell bio.

|

|

The above image is derived from the cover of the Google Books version The Philanthropic Work of Josephine Shaw Lowell by William Rhinelander Stewart, published by Macmillan Company in 1911. The same photo, minus the book title and author's name, appears on a page facing Page 38 and carries the cutline "Josephine Shaw and Col. Charles Russell Lowell, 1863."

Clicking the above image accesses the Google version of Stewart's book.

|

|

Dr. Daniel, who was then attending physician to the Isaac T. Hopper Home of the Women's Prison Association, was an associate of Mrs. Lowell in the Working Women's Society, and had made some investigations for the Tenement House Commission, of which Dr. Felix Adler was chairman.Mrs. Lowell's . . . intention [was] to join in the inspections, but the pressure of other official work prevented.

Dr. Daniel informs me that Mrs. Weidemeyer, of the Charity Organization Society, visited the Essex Market prison with her, and that to all the other station houses and prisons she went alone.

The written report, made by Dr. Daniel to Mrs. Lowell, substantiated the allegations of abuses, and resulted in a conference of public-spirited women, which assembled on Mrs. Lowell's invitation in the autumn of 1886, for the consideration of the need of police matrons in station houses, and of other social questions of municipal interest. . . .

Free lodgings in the station houses were [back then] given indiscriminately to homeless or vagrant men and women, a practice which, Mrs. Lowell believed, increased the evils and abuses found in them.

The charitable and correctional institutions of the city were then administered by one Commission [Dept. of Public Charities and Correction], and any one applying for a night's lodging was given shelter wherever it was sought, so that the same building served for correction and charity, and the station houses, being numerous and accessible, were resorted to, especially in bad weather, by the idle, the vicious, and the unfortunate in large numbers, beside housing those arrested for crime.

Following the conference of women, which was continued in 1887, Mrs. Lowell actively engaged, with other benevolent and public-spirited women, in securing three reforms, which aimed to prevent the recurrence of the disgraceful conditions then found to exist in the station houses:

XXX

Abigail Hopper Gibbons.

|

|

The above image is derived from one appearing elsewhere on this website in a seven-page presentation recounting the history of the Women's Prison Association (WPA) and the role of Abigail Hopper Gibbons played in its founding and its early years.

Clicking the above image accesses that WPA history presentation.

|

|

1. The division of the Department of Charities and Correction into two departments.

2. The appointment of police matrons for all station houses and prisons.

3. The establishment of a municipal lodging house, or houses, for homeless men and women.

Practical and useful reforms, all three, and all of them long since accomplished; but the need of police matrons seemed the most pressing, and received Mrs. Lowell's first attention.

The Women's Prison Association, formed in 1844, was simultaneously at work under the able leadership of Mrs. Gibbons, to secure reformed administration of the city station houses and prisons, and it was largely due to this Association that Chapter 420 of the Laws of 1888, entitled "An Act to provide for Police Matrons in Cities" was placed among the statutes of New York State, May 28 of that year.

Under the provisions of this law, the Board of Commissioners of Police of the cities of New York and Brooklyn was directed within three months after the passage of the act, to designate one or more station houses within their respective cities for the detention and confinement of all women under arrest, upon the appropriation of funds therefor; the Commissioners were further directed to appoint for each station house thus designated not more than two respectable women, to be known as police matrons.

When only one police matron was attached to a station house, she must reside there, or nearby, and respond to any call therefrom at any hour.

"The law further provided that the police matron, subject to the officer in charge, should have the immediate care and charge of all women held under arrest at the station house to which she was attached; also, that women and men should be kept separate and apart in the station houses.

Although the city prisons then had matrons, they were sometimes incompetent, or their services did not cover all the hours of the day.

XXX

The Houses 120 and 118 east Thirtieth Street.

|

|

The above image is derived from a photo on Page 52 of the Google Books version The Philanthropic Work of Josephine Shaw Lowell by William Rhinelander Stewart, published by Macmillan Company in 1911. In 1874, because Effie wanted her daughter to attend school in Manhattan, Francis Shaw purchased a home for them on East 30th St. For years, however, Josephine and Carlotta would return frequently to the Staten Island residence weekends, holidays and vacations. After Mr. Shaw died in 1882, her mother rented the E. 30th street house next door. The houses were made to connect on the first floor. Mother, daughter and grand-daughter lived there as one family. Mrs. Shaw died in 1902. Effie died October 12, 1905.

Clicking the above image accesses the Google version of Stewart's book.

|

|

On this subject, Dr. Daniel mentions the following instance of Mrs. Lowell's method of work:

"Mrs. Lowell's ability to act promptly was demonstrated when conditions, proved to exist in one of the city prisons, were told her.

"At the particular prison, a matron was in attendance from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.; the remainder of the twenty-four hours this woman's prisoners were entirely in the care of men keepers.

"Facts were disclosed, which could neither be talked of openly nor published.

"Mrs. Lowell, hearing this shocking story, went at once to the Commissioners' office and was told that nothing could be done, owing to the lack of appropriations.

"Within half an hour, she convinced the Commissioners that women prisoners must be protected, and a way was opened by them to appoint an additional matron.

"From that day to this, prisoners in that prison have had the protection of a woman."

Notwithstanding the mandatory provisions of the act of 1888, by which the Commissioners of Police of New York and Brooklyn were directed to appoint police matrons within three months from the passage of the act, those officials disobeyed the law for more than two years, until a public scandal in a station house called forth the following letter from Mrs. Lowell, at that time a Commissioner of the State Board of Charities:

XXX

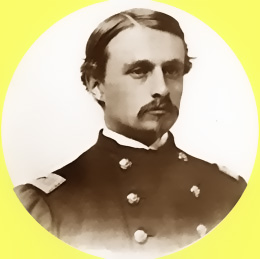

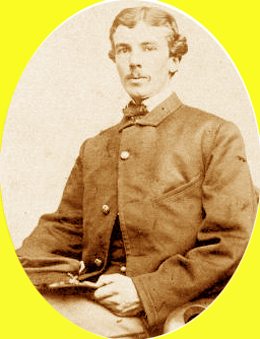

Col. Robert Gould Shaw.

|

|

Above: An image of Col. Shaw derived from one in the Google Books version The Philanthropic Work of Josephine Shaw Lowell by William Rhinelander Stewart, published by Macmillan Company in 1911. Click to access more on him in the book.

Below: An image of Col. Lowell from one on his wikipedia.org page. Click image for more about him in Stewart's book.

|

|

Col. Charles Russell Lowell.

XXX | |

"No. 120 East 30th Street, August 5, 1890.

"To The Board Of Police Of The City Of New York

"Gentlemen:

". . . one of your officers has pleaded guilty and been sentenced to imprisonment for attempted assault on a girl of fifteen, while under the protection of your Board in one of your station houses.

"As your Board has had the power for the past two years to keep all women in the station houses safe from such wrongs, by placing them under the charge of matrons, it does not seem unjust to say that you are responsible for the fearful experience of this young girl, and also for the ruin of the life of the man whom you placed in a position . . .

"In the name of the women who, in the station houses, are still exposed to this horrible danger, in the name of your officers to whom temptation is presented by the existing system, I write to beg you to use at once your power to designate certain station houses where all women shall be detained and placed under the charge of matrons.

"Respectfully,

"Josephine Shaw Lowell."

This letter was published in full, in one or more of the daily papers of New York City, with the statement that it had been received by the Board of Police.

But the Board continued to neglect its duties in this particular, and the pressure upon it was continued by Mrs. Lowell and her earnest associates, in a memorial addressed to the Grand Jury of the City of New York, a draft of which, found among her papers, is evidently in Mrs. Lowell's language. . . .

The Grand Jury apparently took cognizance of this strong appeal, for among Mrs. Lowell's papers is a printed copy of an act amending the Police Matrons Law of 1888, which provides, in Section 7, that the "Board of Estimate and Apportionment in said City of New York is hereby authorized and empowered to reopen the budget for the year 1891 in order to include therein the estimates necessary to carry out the provisions of this act in said city."

At this time, some of the leading New York papers came to the support of the women's crusade for police matrons.

The Sun, under the caption "Women's Side of It," published in its issue of January 4, 1891, a strong and ably written two-column article, in which are described the scenes of degradation and misery discovered by a philanthropic woman, a member of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, in the station houses of Philadelphia three years before, and of her successful efforts there for the appointment of police matrons, and adds

"In New York, such women as Mrs. Josephine Shaw Lowell, Mrs. Mary T. Burt, Miss Grace Dodge, Mrs. E. B. Grannis, and others equally well known, are interesting themselves in this work.

XXX

George William Curtis.

|

|

The above image is derived from one appearing on Page 476 of the Google Books version The Philanthropic Work of Josephine Shaw Lowell by William Rhinelander Stewart, published by Macmillan Company in 1911.

Clicking the above image accesses that book section which provides background about Curtis and the campaign for a civil service system.

|

|

"They have visited the station houses and seen scenes of depravity and misery which, if decency would permit being printed in detail, would arouse the indignation of all humane people."

Further reference was made in this article to conditions in the station houses of New York, and to the brutal treatment recently experienced in one of them by a young girl picked up insensible in the street.

"All night she sat with wild frightened eyes, listening to the oaths and ribald jests of the women in the corridor.

"The next morning, Mrs. Lowell saw her standing behind the bar and listening to the charge against her. . . . She was sent back to the cell on false charges for another night, and then allowed to go back to her husband and baby ruined in reputation. . . .

"Mrs. Lowell investigated the case and found the woman in every way thoroughly respectable and above reproach."

Courage and perseverance triumphed, the budget for 1891 was reopened to make provision for the appointment of police matrons, and the good women of New York had won another notable victory for humanity, over official ignorance and neglect.

Since it was essential to the success of the experiment that suitable women should be appointed, Mrs. Lowell and her associates prepared the examination papers, which, pursuant to the Civil Service regulations, were to be filled out and submitted by the applicants, and drafted the rules to be observed by the matrons appointed.

XXX

Anna Shaw Curtis.

|

|

The above image is derived from one with Josephine Shaw Lowell 1843-1905 & Anna Shaw Curtis 1838-1927; Staten Island True Women - Social Reformer and Church Lay Leader among Prof. Catherine Lavender's web pages in the College of Staten Island Department of History section of CUNY's website. The paper was prepared by Susan McAnanama, a student in Dr. Lavender's "Women in NYC, 1890-1940" course.

Clicking the above image accesses that paper.

|

|

Miss Ellen Collins, who was associated with Mrs. Lowell in this as in others of her philanthropic activities, recalls that she and Mrs. Lowell were requested to attend the first examination conducted under the Civil Service rules, at which a number of capable women who had followed the movement with sympathy, presented themselves as candidates.

The questions were intended to bring out, in strong relief, the individual characters of the applicants.

Memoranda made as the examination progressed were compared and tabulated on its conclusion.

Mrs. Lowell and Miss Collins paid particular attention to the personality of the women, and endeavored to ascertain their motives in applying for the appointments.

Their reports were presented, and included in the records from which the first appointments of police matrons in New York City were made.

Reference to this examination was made in a letter from Mrs. Lowell to her sister-in-law:

"120 East 30TH Street, May 1, 1891. Dear Annie:

"Last week Ellen Collins (a friend of ours ever since the war, when we were together in the Sanitary Committee work) and I, spent three days helping the Civil Service Board examine 120 women applicants for Police Matronship, of which there will probably be twelve appointed at most.

"We talked to each one and asked her questions, based on her written answers in an examination paper, and you may imagine that we were pretty well exhausted.

"There were 28 who were really first rate, about 30 who were good, and the rest were "fair to middling" only.

"It was interesting and encouraging to see the way in which the work of the Civil Service Board is carried on.

XXX

Miss Ellen Collins writing.

|

|

The above image is derived from one appearing with the Ellen Collins obituary in the Jan. 4, 1913 issue of The Survey, a journal of social exploration. The photo depicts Miss Collins, right, making notes at a meeting in Cooper Union. Ladies seated at the table and looking on are identified as Miss Gertrude Stevens, left, and Miss Louisa Lee Schuyler, center.

Clicking the above image accesses The Survey obit for Miss Collins..

|

|

"All Police officers have to go through a severe examination, and only those who pass the highest are sent to the Board of Police, 75, if they want 50, and if the Board skips anyone, they are obliged to give their reasons in writing. "The Secretary told us that the character of the applicants had risen 100 per cent since they first began, about six years ago. The worthless ones find they cannot go through and so they stay away."

The Sun continued to the police matrons the valuable support it gave to the movement for their appointment, and on November 1, 1891, published an article, "What the Matron Does," describing an inspection made of the Elizabeth Street Station, by a representative of that newspaper, accompanied by the matron on duty, in which a favorable account was given of the improved care given the women prisoners, and from which the following excerpts are made:

"Mrs. Josephine Shaw Lowell's recent letter to the Police Commissioners, complaining that the work required of the Matrons recently appointed to several police stations, to look after women prisoners, was too severe, and that their hours of duty were too long, has brought up the question whether or not the new system is a failure. The Matrons are on duty fourteen hours consecutively . . . The Commissioners did not look with favor upon the Police Matron project when it was first urged by charitable women ; . . . however, they made the experiment, and now regard Mrs. Lowell's complaint with little sympathy." . . .

The friendly interest of Mrs. Lowell in the matrons and their charges was continued by subsequent visits to the station houses, for many years, and by interviews and meetings at her own house; and there as everywhere, her strong and attractive personality was helpful to all she met.

A semi-official character was given these visits by Mrs. Lowell's membership of the Women's Prison Reform Committee, and she preserved her card of admission to the city prisons, bearing date March 25, 1904, signed by W. McAdoo, Police Commissioner.

Among her papers on the subject of Police Matrons, is the following

brief statement, written in ink in her large, firm hand, to which she had given additional and unusual emphasis, for such a paper, by her signature :

XXX

Image of menu links to Rikers & Hart Islands USCTs

|

|

The bravery demonstrated by men of Massachusetts' 54th has been credited as contributing to expansion of the U.S. Colored Troops program. NYS' three USCT regiments trained on bases that eventually became NYC DOC facilities: Hart and Rikers Islands. For more about those and other regiments on the two islands and for other Civil War stories with NY Correction connections, click the image above from the "Civil War & Correction" menu page elsewhere on this website.

|

|

"The change in the station houses where the matrons are, since their appointment is simply indescribable."Now everything is quiet, orderly, almost pleasant.

"It used to be horrible to find the drunken men and women prisoners in contiguous cells, perfectly audible to each other, and under the charge of men.

"There are fourteen (?) station houses in New York City and eight (?) in Brooklyn, designated to receive women prisoners, each with a matron constantly on duty.

"The majority of the matrons have been in the service six or seven years, and do very well. They have all been appointed after competitive examinations. There are no female lodgers (or men either) now received in the station houses.

"August, 1898. J. S. Lowell."

With which song of thanksgiving is closed the chapter of Mrs. Lowell's work for Police Matrons.