ElmiraWhen New York's Elmira Reformatory opened in 1876, it rejected 19th century penology's holy trinity of silence, obedience and labor. Elmira's goal would be reform of the convict, and its methods would be psychological rather than physical. Instead of coercing with the lash, Elmira would encourage with rewards. Mass regimentation would yield to classification and individualized treatment. Instead of fixed sentences to fit the crime, the indeterminate sentence would be adjustable to fit the criminal. Rather than outright release after the offender "paid his debt to society," the new parole procedure would assure he did not begin running up a new tab. Elmira quietly redefined the term "reform," until then understood only in purely religious terms. Teaching rather than preaching, they downplayed religious conversion in favor of the more realistic goal of law-abiding behavior. The new reformatory generated tremendous excitement, and pushed American corrections into the future. Elmira's premises--individual treatment, the indeterminate sentence and parole--were universally embraced and would not be seriously questioned until the 1970's, when a new concern for individual liberties and due process would begin to make inroads on the rehabilitative ideal. Brockway and the New Penology Zebulon Reed Brockway, who would open the world's first adult reformatory at Elmira and serve as its superintendent for 24 years, was born in Connecticut in 1827. He began his career as a guard in the Connecticut state prison at Wethersheld in 1848. Three years later, he was lured to Albany to serve as assistant to Amos Pilsbury, warden of the county penitentiary. Pilsbury recommended him as warden for the new municipal alms-house in Albany, where Brockway served for two years. In 1854, Brockway went to Rochester as head of the new Monroe County Penitentiary. Then, in 1861, he went to Detroit to become superintendent of the city house of correction, where he built a national reputation as a capable administrator with a penchant for bold innovation. Brockway experimented with privileges for good conduct, 'half-way" type housing preparatory to release and educational programs. By the late 1860's, the Detroit achievement drew energy from news of similar experiments in Ireland and Australia. The reform-minded Prison Association of New York helped to promote the new ideas. The association's secretary, the Reverend Enoch Wines, joined with Brockway to organize a national prison congress, held in Cincinnati in 1870. Enthusiastic delegates endorsed a Declaration of Principles calling for the reformation of criminals through rewards and appeal to the prisoners' self-interest, a system of marks to grade prisoners' progress and indeterminate sentences "limited only by satisfactory proof of reformation." Those were visionary ideas in search of a government willing to try them. Anticipating an increase in crime as soldiers returned from the Civil War, New York had begun making plans for a new prison. In 1869, the Legislature authorized purchase of a 280-acre site in Elmira and earmarked the new facility for reformatory purposes, restricting it to first offenders between the ages of 16 and 30. The reformatory finally opened on July 24, 1876, with Brockway as warden, when 30 inmates were transferred from Auburn Prison. Others followed to finish construction. These were difficult years. Auburn and Sing Sing, Brockway suspected, were dumping their disciplinary problems on him . . . . The Reformatory Program By 1879, construction was nearly complete. Set atop a hill, the institution's Victorian towers and turrets loomed above the town "like a college or a hospital." With Brockway's input, it had been designed for reformatory work: its cells were almost twice the size of Sing Sing's and configured for separation by prisoner classification. Brockway could now set about the realization of his life's work and dreams. He had in the meantime written the 1877 law authorizing a five-year indeterminate sentence with parole at the discretion of the board of managers. A three-grade system was instituted. All new inmates were placed in the middle grade; six months of perfect marks in school, work and deportment earned promotion to first grade with extra privileges. Another six months of perfect marks earned eligibility for parole. Unsatisfactory marks meant demotion to the next lower grade: demotion to the third grade meant a red suit, the lockstep and loss of correspondence and visiting. The next 20 years saw an explosion of ambitious and resourceful programming activity. Beginning in 1878, several educated inmates taught elementary classes six nights a week, and a professor from the Elmira Women's College conducted courses in geography and the natural sciences for advanced students. The next year, six public school teachers and three attorneys were engaged to teach elementary classes and advanced classes were expanded to include geometry, bookkeeping and physiology. A professor from the Michigan State Normal School was recruited as "moral director" to begin courses in ethics and psychology. Lectures in history and literature were added in the early '80's. In 1882, a summer school was started. Throughout the period, Elmira attracted prominent visitors as "Sunday lecturers." In 1888, an entire building was set aside as a trades school and, by 1894, instruction was provided in 34 trades.

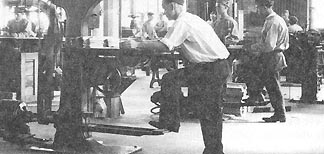

For inmates who did not profit from the regular programs, a professor from Syracuse University was brought down to open a summer class in industrial arts for "dullards"; in 1883 the classes were offered year-round. In 1886, the institution physician started a special program for "low-grade, intractable' inmates consisting of regulated diet, steam baths, massages and calisthenics. He also began systematic studies of prisoners' physical and mental characteristics that would contribute to the "criminal anthropology" movement and eventually lead to isolation of "defective delinquents." With inmates freed from construction work, Brockway began the industrial program with hollow-ware manufacture, shoemaking, an iron foundry and brushmaking. The 1880's, however, was probably the worst possible time in the state's history to introduce industries, as private sector opposition to competition from inmate labor was peaking. In 1888, the Yates Law prohibited all productive inmate industrial work, and Elmira and the prisons faced a crisis. In retrospect, Brockway would regard the Yates Law a blessing, because it freed him of the necessity of revenue generation, "releasing to us the entire time of the prisoners... for direct reformatory training." Within 48 hours of the law's passage, a military program was in full stride and the inmates were drilling five to eight hours a day. Inmates were organized into companies and regiments, with inmate officers and a brass band. Brockway also took this opportunity to shift the trades school program from evenings to days and to adapt the physical education program (originally for "subnormal" inmates) to the entire population. A gymnasium with marble floors, a swimming pool and drill hall, completed in 1890, allowed military and physical training in all weather. A printing press bought for production of internal forms became a vocational and then an informational tool. In 1883, publication of The Summary began, an eight-page weekly digest of world and local news. The Summary was the world's first prisoner newspaper. Elmira was also the first correctional institution to use games baseball, basketball, football and track and field as "treatment" rather than mere diversion. Overcrowding, Excesses, and Brockway's Resignation Brockway adopted a "policy of publicity," and used his new press to hype the program, routinely printing 3,000 copies of the annual reports and 1,500 copies of The Summary. Judges--convinced of Elmira's merits-- sent inmates faster than they could be paroled. Additions to the original 504 cells were made in 1886 and again in 1892, raising the total to 1,296, but by the late 1890's there were nearly 1,500 occupants. At the same time, probation became an increasingly popular judicial option, with the result that the young first offenders for whom Brockway's program was designed were diverted beforehand. With the population growing in number and intractability, the use of punishments increased. So did a dangerous reliance on inmate "monitors" to perform staff functions, including grading and discipline of other inmates.

In 1893, a parolee fought his parole revocation in court, testifying that he had been brutally beaten by Brockway and was afraid to return. Newspapers found other ex-inmates to corroborate the allegations, and pressured Governor Roswell Flower and the State Board of Charities to investigate. . . . . . . .Thus officially vindicated, Brockway carried on much as before until 1899, when a new governor, Theodore Roosevelt, appointed new men to the board of managers. They made an examination of conditions at Elmira and requested funding to repair the "old and rotten" physical plant. They also moved to abolish corporal punishment and--by hiring more guards and civilian teachers--eliminate the inmate monitors, who for years had abused their authority to carry out grudges, traffic in contraband and even run a "sex ring." Worst, from Brockway's perspective, was the new managers' determination to actually manage, denying him the autonomy he had enjoyed since 1876. Brockway retired in 1900 at the age of 73. The "grand old man" of American wardens lived another 20 years, lecturing and consulting, writing his autobiography and serving a term as mayor of Elmira. After Brockway: Development of Classification Modern classification began in Brockway's office. The superintendent interviewed each new arrival, probing into the offender's social, economic, psychological, biological and moral make-up, "until the subjective defect is apparently discovered," and then make a preliminary work and school assignment. He placed the inmates in grades and reviewed their classification continuously. He encouraged cranial measurements and researches into criminal types and developed special programs for defectives.

The next advance was unplanned and serendipitous. To relieve chronic overcrowding, the Legislature approved a second reformatory. The Eastern New York Reformatory at Napanoch opened in 1900, receiving its inmates by transfer from Elmira. Napanoch, still in the building stage, needed construction workers, so Elmira sent on its older and stronger inmates. The precedent was established: Napanoch would provide custody for recidivists, parole violators, trouble-makers and "incorrigibles," and Elmira would concentrate on younger, "hopeful" cases. Meanwhile, Brockway's interest in "defectives" carried over to his successors. In 1908, Dr. Frank Christian, Elmira's new physician, studied 8,000 consecutive commitments and concluded that 37 percent were mental defectives. In 1913, he started a "Special Training Class for Mental Defectives." They were segregated from the general population and relegated to simpler "useful institutional work" such as janitorial duties, mending clothes and shelling peas. In 1917, Dr. Christian, now superintendent, organized a "Psychological Laboratory" where each new admission was sent for a physical examination, social history, an IQ and other psychological tests. Standardized "letters of inquiry" were sent to parents, wives, teachers, ministers, physicians, employers, friends, social service workers and probation or parole officers. The resulting "psychogram" was used to assess, classify and assign the inmate to a work and educational program. In 1939, two prisoners followed Dr. Christian to his car and demanded he drive them out of the prison. Despite a knife held to his throat, the 63-year-old Dr. Christian fought off his assailants until help arrived; he received three stab wounds, narrowly escaping death. He retired three months later after 39 years at Elmira. In 1945, a reception center--the culmination of the classification program initiated by Brockway and refined by Christian--was established on the grounds of the Reformatory. The End of the Reformatory In 1970, the reception center was administratively joined to the main facility and the complex was renamed the Elmira Correctional and Reception Center. Although no longer a reformatory, Elmira's concentration on younger offenders continued into the early 1990's, when DOCS established under-21 facilities in the Washington hub. Elmira's population now averages around 35 years of age. Elmira, now a general confinement facility for adult males, operates a modern correctional program along the lines laid down by Brockway. . . . The indeterminate sentence and parole system has been attacked, and modified, in New York on the grounds that the administrative discretion and differential treatment necessary to administer it are inconsistent with principles of justice (a fact candidly acknowledged by Brockway). But the core of his program--classification with gradations of freedom and privilege, along with an emphasis on development of the whole person, physical,intellectual and spiritual remains at the basis of modern corrections. |