The Bureau: Edward Parke

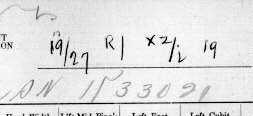

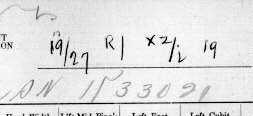

Edward Parke maintained he was the first person in the United States to seriously take up the study of fingerprints. He places the date at which he first read Sir Henry and Sir Galton's books at 1901 which, if true, would justify his claim. . . When the State Prison Department decided to initiate a fingerprint file, Edward helped his father set up a filing system and work out a simplification of Henry's classification formula. . . Throughout 1904 and 1905, Edward wrote several chapters of a book detailing their

classification method. . .

American classification formula from

fingerprint card designed by

Edward Parke (shown below).

|

In August of 1906, Edward got a job with the Prison Department working, for a short time, as a parole officer in Auburn Prison. In September of 1907, he took a position in Sing Sing's Bertillon Identification Unit which allowed him to use his fingerprint expertise. Although Bertillon measurements were still being taken at all state prisons, Edward's job was to fingerprint arriving inmates, file one copy for the prison and forward a duplicate to his father in Albany.

While at Sing Sing, Edward rose to head of the Bertillon Bureau there . . . On May 14, 1913, after a ten-year trial period, the State Legislature passed a law requiring New York's prisons to record fingerprints. Captain Parke's central file had, by that time, become neglected to the point of near-uselessness. On June 26, 1913, Edward was transferred to the main office and assigned the daunting task of straightening out his father's fingerprint collection.

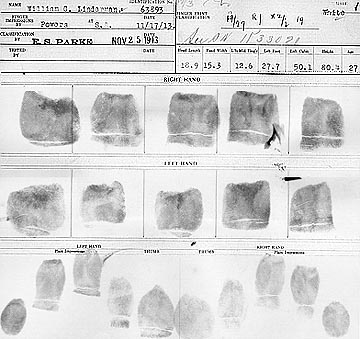

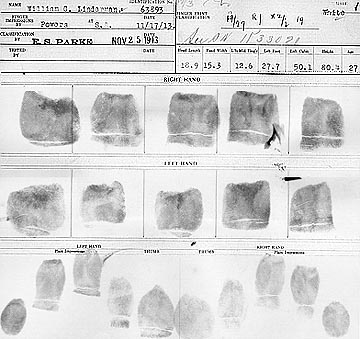

The fingerprint card designed by Edward Parke in 1913.

|

The first thing Edward Parke did was the first thing James Parke had wanted to do: give up the large paper fingerprint sheets. He set to work immediately designing an 8 by 8 inch form of stiff cardboard upon which the inmate's ingerprints, Bertillon measurements and photograph could be recorded. The form was completed after a few months and on October 1, 1913, the New York State Prison Department's Fingerprint Bureau officially opened.

The old fingerprint sheets were gradually phased out. On May 1 of the following year, Superintendent John B. Riley notified all state facilities that, after the first of June,

the central office would no longer accept inmate prints unless they were recorded on the new fingerprint form.

Bertillon measurements were not discontinued, however, and the Bertillon files continued to play a major and active role in the Identification Bureau. While Edward Parke single-handedly attempted to organize the thousands of fingerprint sheets left to him by his father, six women staffed the Bertillon Unit which, by 1914, contained nearly 200,000 cards.

Before very long, the work became too much for Edward to handle alone. In November of 1913, Thurza Myers, one of the Identification Bureau's six Bertillon Indexers, was assigned to the Fingerprint Unit as Edward's assistant. Thurza became the first person outside of the Parke family to learn their system of fingerprint classification and Edward became the leading authority on fingerprint identification in the State of New York.

Thurza Myers

Staff photo of the New York State Bertillon Bureau, August 1914

L to R, Back: Florence de Forest, Thurza Myers. Front: Mary

Morton, Nora Steers, Charlotte Pangburn, Clara Parsons.

|

The woman responsible for preserving Parke's system of fingerprint classification was born in 1890 in the tiny town of Ellenburg, N.Y., not far from the Canadian border.

Thurza came to Albany in June of 1911 . . . Of the six women who worked in the Bertillon Bureau in 1913, Thurza had the least seniority. When Edward Parke needed an assistant to help him with his fingerprint files, there were no willing volunteers, and Thurza, being the most junior member of the unit, was assigned the job.

She turned out to be a capable student, however. By February of 1914 she was classifying prints for Edward's review, and by March she was experienced enough to classify and file without having her work checked. This proved fortunate, as Edward's attention was soon diverted to other matters.

On the night of December 20, 1913, John Barrett was shot and bludgeoned to death in his farmhouse in Palatine Bridge, New York. The only clues left at the scene were a few smudged fingerprints and the imprint of a left hand, stamped in blood, on the side of the house. These pieces of evidence were cut out and brought to the State's Identification Bureau. Superintendent Riley assigned Edward Parke to work on the case.

Edward, unable to match any of the blurred fingerprints, seized upon the idea of matching the shape of the bloody hand print with the hand of one of the suspects.

Using the "plain impressions" of the hands, which are imprinted on every fingerprint record, Edward began measuring the lengths of the fingers and the relationships between those lengths. Over the next several months he studied thousands of hand prints, while in Palatine Bridge the

investigation began to center on Lewis Roach, a local farmhand.

Late on the night of June 23, 1914, Edward Parke and Deputy Sheriff Earl Van Wie visited Roach's house. They roused Roach out of bed and brought him out to the side of the road where Edward inked Roach's entire hand and let it drop on a piece of cardboard placed over the curved surface of Roach's mail box.

Back in Albany, Edward compared the shape of Roach's hand to the impression taken from the side of Barrett's house. He concluded that Roach had made the bloody mark and ordered his arrest.

The ensuing trial was a media sensation. On December 10, 1914, Edward took the stand. Confident in his position as the head of New York's Fingerprint Bureau, Edward claimed expert status and told how he was the first man in America to take up the study of fingerprints. He could, he assured the prosecutor, place Roach at the scene of the crime.

In the end, however, Edward's expertise was called into question. The defense attorney successfully challenged Edward's claims, making him appear inexperienced, ignorant and confused. Edward was not allowed to state for the court his opinion that the bloody palm print found on Barrett's house matched the hand of Mr. Roach.

Dr. Hamilton, a forensic scientist who followed Edward to the stand, ably deflected the defense's challenges and stated with certainty that the fingerprints found at the crime scene did indeed belong to Roach.

These events reportedly unnerved Edward, driving him to depression and bouts of erratic behavior.

During much of the time prior to the trial, Thurza operated the growing fingerprint unit on her own. Soon after the trial, the Prison Department sent Edward to the Panama Exposition, leaving Thurza, once again, in charge of fingerprint identification.

Edward returned in late June of 1915 to resume his duties, but a short time later, on July 7, his sister Bessie committed suicide. This exacerbated Edward's depression. He left his position on August 16, traveled to New York City and attempted to kill himself. He was confined to an institution for several months and on September 9, 1916, officially resigned from State service. He committed suicide a year later, on September 5, 1917.

With less than two years experience, Thurza became solely responsible for the Prison Department's Fingerprint Unit. The central file contained nearly 50,000 records and

received over 2,000 inquiries a year. It was not long before Thurza, herself, was in need of an assistant.

Charlotte Pangburn, the Bertillon Indexer with the next lowest seniority, was subsequently chosen to learn the Parkes' fingerprint system. Thurza began training Charlotte in the fall of 1915 and by the end of that year Charlotte was sufficiently skilled to classify on her own.

On July 1, 1916, Thurza Myers married Frederick Kurth, a shoe salesman. She resigned from the department two years later, on September 1, 1918.

|