Introduction

. . . Prior to the nineteenth century, identification systems generally involved dismemberment, the scarring of various body parts, or the forced application of tattoos. Advances in civilization and criminal rights laws put an end to these pragmatic, yet unquestionably barbaric, means of identification by the latter part of the 1800's but no practical methods were devised to take their place. . .

The absence of a truly effective means of personal identification put the legal authorities of the day at a formidable disadvantage. The only way to identify a criminal as a repeat offender was to have someone present at his trial who could recognize him from a prior offense. This was hardly a reliable method. . .

The advent of photography eased the strain on the officers' memories somewhat, but the inability to categorize and file photographs--not to mention the effects of age, hair dye and shaving equipment--eliminated photography as a solution to the identification conundrum.

One popular method of criminal identification in England during the late 1800's was the Tattoo Index. Since it was noted that many in the criminal profession were "addicted to tattoos," it was deemed advisable to begin detailing their locations and appearance. These records were classified and placed in a central index for future retrieval.

Identifications were made through this index but, quite predictably, criminals soon developed the habit of periodically altering their tattoos. . .

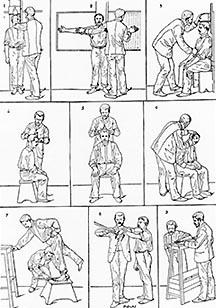

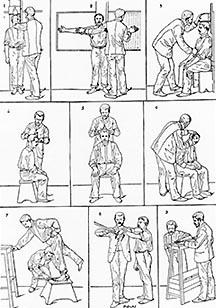

Taking Bertillon Measurements, a process

that could take up to 20 minutes.

|

The Bertillon System

In 1893, New York State's Prison Department was experiencing the same difficulties as every other police agency and criminal institution throughout the world. There was simply no accurate way to identify, and thereby appropriately incarcerate, recidivists. Too many hardened criminals were being sentenced as first offenders.

Seeking to solve this problem, the Superintendent of Prisons, Austin Lathrop, sent his Chief Clerk, Charles K. Baker, to Europe to study the Bertillon System.

Bertillonage, the invention of French ethnologist Alphonse Bertillon, had been introduced in Paris ten years earlier and by the time of Baker's visit had become the standard method of criminal Identification throughout most of Europe. . .

Bertillon took measurements of certain bony portions of the body, among them the skull width, foot length, cubit, trunk and left middle finger. These measurements, along with hair color, eye color and front and side view photographs, were recorded on cardboard forms measuring six and a half inches tall by five and a half inches wide.

By dividing each of the measurements into small, medium and large groupings, Bertillon could place the dimensions of any single person into one of 243 distinct categories. Further subdivision by eye and hair color provided for 1,701 separate groupings.

Upon arrest, a criminal was measured, described and photographed. The completed card was indexed and placed in the appropriate category. In a file of 5,000 records, for example, each of the primary categories would hold only about 20 cards. It was therefore not difficult to compare the new record to each of the other cards in the same category. If a match was discovered, the new offense was recorded on the criminal's card.

Bertillon submitted a report detailing his system but the Prefecture, thinking it was a joke, ignored it.

In the winter of 1881, the Prefecture retired and his replacement agreed to implement the system. It was officially adopted by the Paris Police in 1882 and quickly spread throughout France, Europe and the rest of the world. In 1887 it was introduced into the United States by Major R. W. McClaughry, warden of the Illinois State Penitentiary. . .

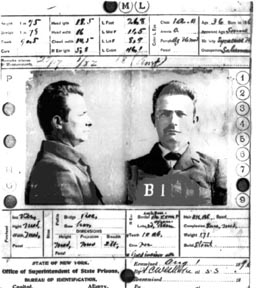

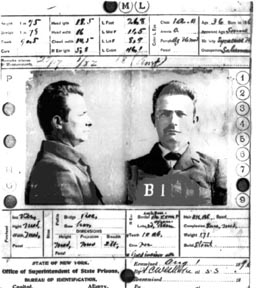

The first criminal identification card filed

by the New York State Bertillon Bureau. |

The NY State Bertillon Bureau

Charles K. Baker studied the Bertillon files in Paris and London and returned to New York with a copy of the second edition of Bertillon's System, published in France in 1893. The book, written in French, had to be forwarded to Major McClaughry in Illinois who supervised its translation into English.

On June 28, 1893, Florence de Forest was hired to the position of indexer for the Bertillon System. Under the supervision of Baker, de Forest and another clerk, Frederick Hicks Duel, designed an office which could accommodate the Bertillon files. . .On May ninth of [1896], a law was passed authorizing the recording and filing of measurements of all inmates "confined or hereinafter received under sentence in the various State Prisons, Reformatory and penitentiaries."

The Bureau of Identification was thereby created within the State Department of Prisons and set up in Room 111 of the New York State Capitol building.

This proved to be no small task. In his 1896 annual report, Superintendent Lathrop noted that the labor to introduce the Bertillon System, due to its being "new and poorly understood," was greater than either he or the Legislature had anticipated.

A program for teaching the intricacies of the Bertillon system, as well as criminal photography, was established at Sing Sing Prison on July 15, 1896, and on September 1, the measuring, describing and photographing of 8,000 inmates was officially begun.

Prisoners were measured at each of the state's prisons and duplicate Bertillon Cards made up. One copy was kept at the prison, the other was sent to the Albany Office to be indexed and added to the master Bertillon File.

The NY State Bertillon Bureau in 1902 |

After his trip to Europe and initial involvement in setting up the Identification Unit, Baker returned to his other duties, leaving the fledgling bureau in the hands of Miss de Forest and two female clerks.

By the end of the first year of operation, 16,000 Bertillon cards were on file and 131 criminals received at State Prisons as "first offenders" were found to have prior records. . .

Though encouraged by the initial successes of the system, the Superintendent understood that its full potential had yet to be realized and called on the State Legislature to expand its use. . .the new Superintendent of State Prisons, Cornelius V. Collins, in his annual report for 1898, promoted as fact Lathrop's suggestion of a Bertillon-influenced migration of criminals to other states "in which they can more safely pursue their vocation." This, he asserted, proved the need for a national central bureau of identification, headquartered, naturally, in Albany, New York. . .New York's bureau, after only two years of operation, contained 24,000 Bertillon cards, making it by far the largest in the country. . .

Attempts to establish a national identification bureau had begun as early as 1871, when a meeting of police executives took place in St. Louis, Missouri. . .

Efforts were renewed in 1896, and a resolution was made by the National Chiefs of Police Union which resulted in the establishment of the National Bureau of Identification, fore-runner of the FBI, in Chicago on October 20, 1897, a full year before Superintendent Collins made his proposal. . . The State Legislature, in 1900, passed a law allowing the Prison Department to accept Bertillon cards from nearly every penal institution in the United States and Canada. By the following year, twelve hundred out-of-state cards had been received, enabling Superintendent Collins to call New York's Bertillon file "the Central Bureau for New York State, 17 other States and Canada since 1900."

|