|

|

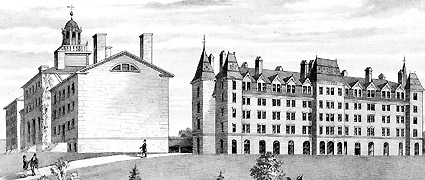

between Auburn Theological Seminary & Auburn State Prison ©

As warden and agent, Elam Lynds was too busy trying to make the prison pay for itself; he believed that the prison

should be self-supporting through the labor of convicts and even show a profit to the State. Every other philosophy,

reformation of the offender, the development of saleable skills and the habits of industry and sobriety were considered

to be secondary aims of imprisonment.

Under Lynds' direction and with his approval, convicts were placed under a stern and coercive system known as the

silent

system or "Auburn System" in order to get work done. The highly structured, no-nonsense approach was satisfactory

economically, but theologians and interested citizens were disturbed by the most striking feature of the system - the

physical cruelty to the convicts - for the lash was often used to enforce discipline.

Elam Lynds (sketch above) was a key figure both in developing what became known as the Auburn System and in exporting it beyond Auburn. He had begun his correction career as a staff member at Auburn prison when it opened in 1817 and rose to become its warden and then Sing Sing's.

In fact, the original Sing Sing was built by a hundred inmates from Auburn.

Shackled in irons, they were transported in 1825 by boat via the Erie Canal and the Hudson to the chosen site, an abandoned mine in a village whose name derived from the area's original native tribe, the Sint Sinck.

Supervising the convicts' transport and their construction work was Warden Lynds. In effect, he made Sing Sing an "Auburn on the Hudson."

Its proximity to New York City, the media capital of the world, resulted in the Westchester institution eventually surpassing Auburn in terms of name recognition among the general public.

[Image selection & caption by NYCHS webmaster]

In retrospect, it is easy to misjudge and over estimate the severity of the disciplinary features of Auburn Prison during

the early years. The rules were rigid and the punishment speedy and harsh; however, well behaved prisoners suffered

little physical punishment. Nevertheless conditions of living in the prison were extremely difficult and demoralizing for

every prisoner who had to work whether he was cooperative or not.

The construction work on the prison went rapidly forward until 1823 when the massive main hall and wings, extensive

workshops, a dam, and an enclosing wall 201 feet high were completed. By 1824 the number of prisoners was

increased to over 600 men. Auburn Prison now became a great, smooth running industrial machine under Lynds'

brutal and sadistic leadership.

Seminary officials held that the economic stability of the institution was not enough, the impact on the individual

inmate should also be taken into consideration. They contended that an education and religious rebuilding policy

should follow the breaking of the convict so that he might ultimately return to free society not merely as a chastened

but actually a better man.

Professors from Auburn Theological Seminary found support for their efforts to assist prisoners from an unexpected

source,

the Reverend Louis Dwight, founder of the Prison Discipline Society located in Boston, Massachusetts, came to Auburn. The success of the

Auburn System had attracted his attention, and inspired, he wanted not only to spread the benefits of the Auburn System to criminals but also

to see some of its principles adapted in colleges, academies and even in private homes, any place where discipline was needed. A promoter of

prison betterment, he sent the Reverend Jared Curtis to Auburn to work with clergy from the seminary in 1824.

Elam Lynds approved of the arrival of the Reverend Curtis but refused to pay him any salary. The society from Boston had to pay for Curtis'

upkeep for several years. Undaunted, he began his labors. Shortly afterwards Elam Lynds was put in charge of the erection of a new prison at

Ossining, New York. During the period of changeover in the administrative staff at the prison, Jared, acting with missionary zeal, seized the

opportunity to expand the religious program inside the prison.

Working with the seminary staff and Gershom Powers, Principal Keeper, Curtis established a sabbath day school for prisoners in 1825.

Sabbath school was conducted on Sunday morning before meeting, about one and a half hour in the chapel by the students of the theological

seminary, very much to their credit and ability.

After Auburn, Rev. Jared Curtis served as chaplain at Massachusetts State Prison in Charlestown. Between 1829 and 1831, he interviewed more than 300 inmates at the prison and recorded their biographies in two leatherbound notebooks discovered in 1998.

Transcribed and annotated, the notebooks form the basis of a Massachusetts Historical Society 2001 book Buried from the World: Inside the Massachusetts State Prison, 1829-1831, The Memorandum Books of the Rev. Jared Curtis," edited by Philip F. Gura whose Introduction places Curtis' text into historical context.

[Image selection & caption by NYCHS webmaster]

Sunday at Auburn Prison was the only day of the week without work for the convicts. After the usual breakfast in the messhall they were

marched back to their cells, where, except for the period of church services, they remained for the rest of the day. It was the hardest day of the

week to endure because there

was absolutely nothing to do in the close confines of the cell.

The Sunday school privilege was embraced by about one fourth of the population. It was the only alleviation of the

monotony of confinement in the cell during the entire week.

Convicts choosing church remained in their seats in the mess hall after the close of breakfast and were taken by

keepers into the chapel where they were taught by some twenty young seminarians who volunteered their services.

The resident chaplain had general supervision over the sabbath school. He was accompanied by every keeper in the

prison except two who were relieved of the obligation to be in the chapel. Any conversation whatsoever between the

young teachers from the community on any subject other than the lessons was rigorously forbidden and closely

monitored.

On Sundays divine services followed sabbath school and were held at 9:00 A.M. The convicts attending services

generally gave respectful attention, and many of them joined in the prayers of the church with reverence and devotion.

The task of the seminarians wasn't always easy. Students found that a large percentage of the prisoners were not

qualified to read the bible, the only book they were allowed to have. Some foreigners and native born did not even

know the alphabet. In addition to bible study and religious instruction, seminarians taught reading, writing and basic

arithmetic. More than three fourths of the population could barely read and write and not one in ten possessed any

high degree of intelligence. Despite the lamentable ignorance of immigrants the students engaged in evangelical

labors as far as humanly possible.

|